Thousands of Indonesian women trafficked to Hong Kong face exploitation and risk domestic “slavery”

![]()

There are more than 300,000 migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong, with about half from Indonesia and nearly all are women. © Amnesty International

Thousands of Indonesian women trafficked to Hong Kong risk slavery-like conditions as domestic workers, with both governments failing to protect them from widespread abuse and exploitation, said Amnesty International.

A new report, Exploited for Profit, Failed by Governments, exposes how Indonesian recruitment agencies and placement agents in Hong Kong traffic Indonesian women for exploitation and forced labour. Abuses include restrictions on freedom of movement, physical and sexual violence, lack of food, and excessive and exploitative hours.

“From the moment the women are tricked into signing up for work in Hong Kong, they are trapped in a cycle of exploitation with cases that amount to modern-day slavery,” said Norma Kang Muico, Asia-Pacific Migrant Rights Researcher at Amnesty International.

The findings are based on in-depth interviews with 97 Indonesian migrant domestic workers and supported by a survey of nearly 1,000 women by the Indonesian Migrant Workers Union.

There are more than 300,000 migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong, with about half from Indonesia and nearly all are women. Lured with the promise of well-paid jobs the reality for the women could not be more different.

One woman told Amnesty International how she was beaten by her employer: “He kicked me from behind and dragged me by my clothes to my room. After locking the door, he smacked and punched me. He pushed me to the ground and kicked me some more. I was black and blue all over – my face, arms and legs. My mouth and forehead were bleeding.”

Systemic failures by both the Hong Kong and Indonesian governments to protect migrant domestic workers from exploitation are highlighted in the report. Some of the authorities’ actions put women at even greater risk of abuse.

“It is inexcusable that the Hong Kong and Indonesian governments turn a blind eye to the trafficking of thousands of vulnerable women for forced labour. The authorities may point to a raft of national laws that supposedly protect these women but such laws are rarely enforced,” said Muico.

In Indonesia, prospective migrant domestic workers are compelled to go through government-licensed recruitment agencies including for pre-departure training.

These agencies, and the brokers that act for them, routinely deceive women about salaries and fees, confiscate identity documents and other property as collateral, and charge fees in excess of those permitted by law. Full fees are imposed from the outset of training, trapping the women with crippling debt should they withdraw.

Lestari, 29, told of when she first arrived at a training centre: “I was shocked. It was surrounded by high fences and all the women had their hair cut short. I was given a piece of paper with English writing on it. All I could read was the number 27 million. The staff told me, ‘You have to sign this.’ There were about 30 of us; we just did as we were told. Afterwards, they said ‘What you have signed means that if you decide to leave you have to pay us 27 million rupiah (US$ 2700).’ “

Women from several different training centres also reported that they were forced to have a contraception injection. Many women said the training staff frequently taunted, abused and threatened them with the cancellation of their employment application. The vast majority could not freely leave the training centres.

The report also exposes that recruitment agencies routinely fail to provide migrant workers with legally required documentation including their contract, mandatory insurance and foreign employment identity card which also undermines their means of redress.

When a migrant domestic worker arrives in Hong Kong, they are tightly controlled by their local placement agency and often by their employer.

The vast majority of the women interviewed by Amnesty International had their documents taken by either their employer or the placement agency in Hong Kong. About a third were not allowed to leave their employer’s house.

Amnesty International found that interviewees worked on average 17 hours a day; numerous respondents did not receive the statutory Minimum Allowable Wage, were prohibited from practising their faith, and did not receive a weekly day off.

Women are trapped into this cycle of forced labour by excessive debts that cover opaque and excessive recruitment fees.

Recruitment agencies in Indonesia and placement agents in Hong Kong collude in order to circumvent the legal limits they can charge migrant domestic workers. Amnesty International found most women are charged way above the legal limits.

Agencies circumvent the law by collecting the excessive payments via a variety of third party schemes, including finance companies.

Despite this, Hong Kong’s Labour Commissioner revoked only two placement agencies’ licences in 2012 and only one in the first four months of 2013.

“Recruitment and placement agents are flagrantly breaching laws designed to protect migrant domestic workers from abuse. The near total lack of action by Hong Kong and Indonesian authorities means these women continue to be exploited for profit,” said Muico.

No escape: Trapped and abused

Once in Hong Kong, the fear of being driven further into debt through repeat recruitment charges to access a new employer often means women are trapped with an abusive employer.

Two-thirds of migrant domestic workers interviewed by Amnesty International had been subject to physical or psychological abuse. The requirement that migrant domestic workers live with their employer increases their isolation, and places them at further risk of abuse.

One woman recalled how “the wife physically abused me on a regular basis. Once she ordered her two dogs to bite me. I had about ten bites on my body, which broke the skin and bled. She recorded it on her mobile phone, which she constantly played back laughing.”

Women told Amnesty International that contracts could be terminated if they complained about their treatment, or if the placement agency manipulated the situation in order to collect a new recruitment fee.

Underpayment is a widespread problem. Yet, in the two-year period up to May 2012, just 342 cases of underpayment were lodged out of a total population of more than 300,000 migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong.

“We need to see current laws enforced and people face justice for the exploitation. Only then will we start to see an end to forced labour from Indonesia to Hong Kong,” said Muico.

Hong Kong’s laws stipulate that migrant domestic workers must find new employment and get an approved work visa within two weeks of the termination of their contract, or they must leave Hong Kong.

This pressures workers to stay in an abusive situation because they know that if they leave their job, they are unlikely to find new employment in two weeks and therefore must leave the country. For many this would make it impossible to repay the recruitment fees or support their families.

“The entire system is loaded against migrant domestic workers. If the Hong Kong government is serious about protecting these women, it would abolish the Two Week Rule and the live-in requirement which place women at greater risk of abuse,” said Muico.

“Both the Indonesian and Hong Kong governments need to show genuine commitment to tackling the human and labour rights violations exposed in this report.”

Amnesty International is calling on both governments to swiftly ratify and implement the International Labour Organization’s Domestic Workers Convention.

Related Articles

TURKEY: HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH says

![]()

The Cizre Report. The situation in Turkey at the moment does not bode well for an investigation into these crimes against humanity

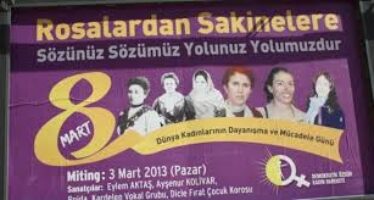

Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin turned PKK members!

![]()

ANF – Diyarbak?r/Amed  Diyarbak?r State prosecutors have assumed Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin, whose names featured on posters for

Pakistan forces accused of torture and killings

![]()

AP Relatives of missing persons from Balochistan sit outside a press club during a protest in Islamabad Security forces have seized