The day GCHQ came to call on the Guardian

![]()

In this exclusive extract from his book on Edward Snowden, Luke Harding gives the inside take on what happened when British agents ordered the destruction of Guardian computers

Since David Cameron became prime minister, Alan Rusbridger had spent barely half an hour with him. “It wasn’t a warm or constructive relationship,” Rusbridger says. But the day after the Guardian published its first GCHQ story, showing that Britain’s intelligence agency had bugged foreign leaders at two G20 summits, Cameron’s press officer, Craig Oliver, called Rusbridger. He said officials were unhappy with the G20 revelations, and some of them wanted to chuck Rusbridger in jail. “But we are not going to do that.”

Next came a personal visit from Cameron’s most lofty emissary, the cabinet secretary Sir Jeremy Heywood. Rusbridger explained that British action would be futile: Snowden’s material now existed in several non-British jurisdictions, including New York, Berlin and Rio. Heywood argued that the Guardian was a target for foreign powers. It might be penetrated by Chinese agents. “Do you know how many Chinese agents are on your staff?” He gestured at the flats visible from the Guardian windows and said, “I wonder where our guys are?” It was impossible to tell if he was joking.

Rusbridger agreed to partner with two US media organisations in order to secure the data. AÂ small selection of edited documents was sent off, heavily encrypted, via FedEx to independent news website ProPublica, and a collaboration was agreed with Jill Abramson, executive editor of the New York Times. The data was now safely on US soil, protected by the first amendment of the constitution.

Two weeks passed, with the Guardian continuing to publish revelations from the NSA files. Then, on Friday 12 July, Heywood reappeared with Oliver. Their message: the Guardian must hand back the files. The mood in government seemed to be hardening, though it was scarcely better informed. “We believe you have 30 to 40 documents,” said Heywood. “We are worried about their security.”

Rusbridger said: “You do realise there is a copy [of the documents] in America?” Heywood replied: “We can do this nicely, or we can go to law.” Then Rusbridger suggested an apparent compromise: that GCHQ could send technical experts to the Guardian to advise staff on how the material could be handled securely. And, possibly in due course, destroyed.

Three nights later, Rusbridger was having a quiet beer in the Crown, a pub not far from the Guardian’s offices. A text arrived from Oliver. Had the editor set up a meeting with Oliver Robbins, Cameron’s deputy national security adviser?

“JH [Heywood] is concerned you have not agreed the meeting he suggested.”

Rusbridger was nonplussed. He texted back: “About security measures?”

Oliver: “About handing the material back.”

Rusbridger: “I thought he suggested meeting about security measures?”

Oliver: “No. He is very clear. The meeting is about getting the material back.”

Rusbridger told the press secretary there hadn’t been a deal to return the Snowden files.

Oliver was blunt: “You’ve had your fun. Now it’s time to hand the files back.”

The next morning, Robbins called. He announced that it was “all over”. Ministers needed urgent assurances that Snowden’s files had been “destroyed”. He said GCHQ technicians also wanted to inspect the files to see if a third party had intercepted them.

Rusbridger repeated: “This doesn’t make sense. It’s in US hands. We will go on reporting from the US. You are going to lose any sense of control over the conditions. You’re not going to have this chat with US news organisations.”

Rusbridger then asked: “Are you saying explicitly, if we don’t do this, you will close us down?”

“I’m saying this,” Robbins agreed.

It was never entirely clear if Robbins meant an injunction or a visit from the police. Later that week, while Rusbridger was at his annual piano camp in France, Robbins spoke to deputy editor Paul Johnson and said the government wanted to seize the Guardian’s computers. Johnson refused. He cited a duty to Snowden and to Guardian journalists. The deputy editor offered another way forward: to avoid being closed down, the Guardian would bash up its own computers under GCHQ’s tutelage. Robbins agreed. It was a parody of luddism: men were sent in to smash the machines.

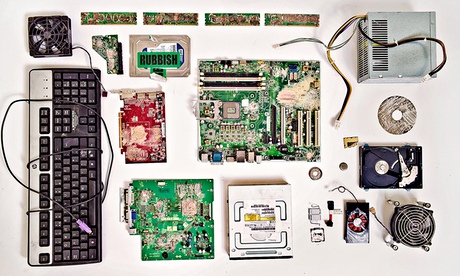

The hard drives used to store documents leaked by Edward Snowden are destroyed in the basement of the Guardian’s London offices. Photograph: Graeme Robertson for the Guardian

The hard drives used to store documents leaked by Edward Snowden are destroyed in the basement of the Guardian’s London offices. Photograph: Graeme Robertson for the Guardian

On Friday 19 July, two men from GCHQ paid a visit to the Guardian. Their names were given as “Ian” and “Chris”. They met with Guardian executive Sheila Fitzsimons. Ian told her: “You have got plastic cups on your table. Plastic cups can be turned into microphones. The Russians can send a laser beam through your window and turn them into a listening device.”

Two days later they came back, this time with Robbins. Ian explained how he himself would have broken into the Guardian: “I would have given the guard £5k and got him to install a dummy keyboard. Black ops would have got it back. We would have seen everything you did.” (The plan made several wildly optimistic assumptions.)

The GCHQ team opened up their rucksack. Inside was what looked like a large microwave oven. This strange object was a degausser. Its purpose is to destroy magnetic fields, thereby erasing hard drives and data.

Ian: “You’ll need one of these.”

Johnson: “We’ll buy our own, thanks.”

Ian: “No, you won’t. It costs £30,000.”

Johnson: “OK, we probably won’t then.”

The Guardian did agree to purchase everything else the government spy agency recommended: angle-grinders, Dremels (a drill with a revolving bit), masks. “There will be a lot of smoke and fire,” Ian warned.

At midday the next day, Saturday 20 July, Ian and Chris joined three senior Guardian staff members in a windowless concrete basement. Directed by Ian, they took it in turns to smash up bits of computer. It was sweaty work. Soon there were sparks and flames, and a lot of dust.

Ian lamented that because of the GCHQ revelations, he would no longer be able to use his favourite joke. He used to go to graduate recruitment fairs looking to attract bright candidates to a career in government spying. He would wrap up his speech by saying, “If you want to take it further, telephone your mum and tell her. We will do the rest!” Now, he complained, the spy agency’s press office had forbidden the gag.

As the bashing and deconstruction continued, the two GCHQ men took photos with their iPhones. Then the journalists fed the pieces into the degausser. Everyone stood back. Nothing happened. Then, finally, a loud pop.

It had taken three hours. The data was destroyed, beyond reach of Russian spies with trigonometric lasers. The spooks and the Guardian team shook hands. Ian and Chris left carrying bags of shopping: presents for their families.

This extraordinary moment was half pantomime, half Stasi. But it was not yet the high tide of British official heavy-handedness. That was still to come.

• © Luke Harding 2014

Related Articles

ALL AT SEA – THE ABUSE OF HUMAN RIGHTS ABOARD ILLEGAL FISHING VESSELS

![]()

ALL AT SEA – THE ABUSE OF HUMAN RIGHTS ABOARD ILLEGAL FISHING VESSELS In the year that the International Maritime

More babies for a strong Turkey

![]()

NURAY MERT Until recently, it used to be considered almost blasphemous to talk about “the rise of authoritarian politics in

Domestic violence increases at weekends

![]()

According to a report prepared by a subcommittee of the Parliamentary Commission on Equal Opportunity for Women and Men said