“Şervano” – The song of resistance

![]()

The Kurdish people’s resistance against the invasion of northern and eastern Syria by the Turkish army and its proxies continues. Since the beginning of the war of aggression on October 9, 2018, Kurds in Kurdistan and all over the world responded to the occupation in a variety of ways, from political work to street protest and physical self-defence. Their resistance has received much support from internationalists around the world, who stand with them shoulder to shoulder in solidarity to put an end to the fascist AKP-regime of the Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Art has always played a big role in the history of the Kurdish people and their struggles. Amongst others, the song “Şervano” has come to be the symbol of Rojava’s resistance against Turkish state fascism. Released in the same week as the beginning of the Turkish army’s “Peace Spring” operation, the song has become an important part of protests, the fields, and the front lines. It is even played at funerals in honor of the martyrs, accompanied by the singing of the attendants, who know it by heart.

The song became iconic with the circulation of videos from the funeral of YPG fighter Yusif Nebi, who had asked his family not to cry, but to sing and dance, if he dies in combat. Surrounded by large crowds of mourners, his brother and mother danced as an act of resistance against fascism.

The following interview with the composer was conducted by the Germany-based Kurdistan Report magazine. “Şervano” was written by Kurdish artist Şêro Hindê, who is working at “Hûnergeha Welat” (atelier of the homeland) in Rojava, and is also a member of the Rojava Film Commune. He is the director of the documentaries “Darên bi tenê” (Lonely Trees) and “Bajarên wêrankirî” (Destroyed Cities).

What were the circumstances in which the song “Şervano” was created? Where was the videoclip shot?

On the evening the Turkish government and its allies started the invasion on the 9th of October, we were in Qamişlo together with the musician Mehmûd Berazî and the author Ibrahim Feqe. Together, we wrote the song and composed the music. In the meantime bombs were dropping on Qamişlo, killing six people and injuring many more.

That night was very meaningful because the resistance fighters tirelessly and fearlessly took up position to protect the civilian populations and at the same time to prepare them for war again. The sight of those brave fighters persuaded us to put down what we saw in writing and composition. So we literarily saw the song “Şervano” in front of our eyes and on the following day, we started shooting the video based on the events of the previous night. We consciously worked without extravagant images and techniques in order to have be as authentic as possible.

The People’s Protection Unit (YPG) fighter from the video, Elî Feqe, is also a member of the Rojava Film Commune. He is a cameraman and an active role in the cinematic art.

Did you expect such a big impact of “Şervano”? What were the reactions?

We expected the song to reach and move people, but we too were surprised about the dimensions of the affect. We always try to create art, which reflects the Zeitgeist. However, it is important for us to express, keep alive and do justice to our centuries-old art traditions and to express our folkloric culture and dengbej music.

I would like to emphasize that our comrade Mehmûd Berazî, the composer of “Şervano”, makes the greatest contributions to music in Rojava and has the strongest influence.

The people love our songs, especially “Şervano”. Certainly, there have been other popular songs before, such as “Nivişta Gerilla”, “Tîna Çiya”, “Edlaye” and “Tola Salanîya Efrînê”, which are also often played at the funerals of our fallen friends, at protests or at the frontline. Essential elements of this music culture are the female and male resistance fighters, who show no fear of the enemy. Of course our musical work influences and touches us as much as anyone else. The emotional specificities of our artwork stem from the love and the esteem that is displayed towards us.

This became obvious also through the martyr Yusuf Nebî. His last will was that the people should not cry at his burial, but dance instead. Following his last will, his family played the song “Şervano” at the funeral, sang along the meaningful verses and danced. This sight was both, very painful and moving at the same time. For us as for everyone else.

You continue your work during the revolution. What do you do?

We were artistically active before the start of the revolution already. However, we couldn’t express ourselves as freely as now. Indeed, it’s astonishing that we feel freer than before in the development of our art, considering the adverse living conditions, the intensity of the war, the daily losses of our fighters and the civil fatalities. In this way, we as Kurdish artists want to make our contribution to the revolution. A revolution has different areas. Our task is it to convey to the outside the emotions and the spirit of the revolution in relation with the pain that our people have to suffer. In doing so, we don’t mind how the public interprets our art, whether positively or negatively. Our primary goal is to do justice to our people. To illustrate as well as relieve the suffering and to keep their morale up.

We also produce movies. The Rojava Film Commune was founded in 2015. We shoot documentaries, short movies, clips and feature films. I personally primarily focus on music, but also on my movie projects. At the moment I produce a documentary about the dengbej music culture. With the title “Darên bi tenê” (Lonely Trees), we documented dengbej songs in Şengal (Sinjar). We also produced a documentary about the life of the unforgettable artist Mihemmed Şêxo. I express myself best with the help of music.

As artists of the Rojava Film Commune and of Hûnergeha Welat, we want to add new elements to the revolution’s art. We don’t want to spread classic, well-known slogan-like art, but rather reflect the present, revolutionary spirit and feelings of Rojava’s society.

Do you face any difficulties during your work?

We work under very harsh conditions, in the midst of a war. Still, we strive to capture sharp photos and clear sounds. Our work is only possible thanks to the collective institutions, because we resist all together. As much as times of resistance are filled with creativity, they are also connected to difficulties. Big projects obviously aren’t possible in the midst of war. We have started a big research project about the dengbêj songs from Rojava. Among other things, we wanted to record some from Dicle (Tigris) to Xabûr and to piece them together in a documentary. But because of the current war conditions, we were forced to let it rest. Our only possibility at the moment is to show to the public, with the help of our projects, the omnipresence of the resistance. But unfortunately that’s not enough. For the realization of our projects, we need resources that are provided sufficiently to other institutions, which neither want to collaborate with us, nor are connected to us or Rojava in any way. They steal our projects and sell them as their own. In the near future, we want to take measures to prevent those and further thefts of course.

Are publications of further projects to be expected?

At the moment we especially work on projects, which primarily document the resistance. An important site of this great and strong resistance is Serê Kanîye (Ras al-Ain). We want to record this great resistance for history, with the help of art projects.

It is important for us to not produce typical revolution movies, but to realize projects, which create the consciousness among people to understand that we are those for whom the resistance fighters fight and sacrifice their lives. This is the direction of our work and it will be revealed in the near future. As much as we receive love and appreciation from the people, sometimes we also get criticism. This is important for the improvement of our further projects. Our singers Xalît Derîk, Haci Musa, Sîdar, Eyşe and Şefîka Şehriban Güneş, who always sing centuries-old folk songs with deep feelings, try to keep alive the cultural folk music.

How was Hûnergeha Welat founded and how is it made up?

Hûnergeha Welat was founded on the first of July 2014 in Qamişlo. There are two different areas: music and documentation. Every year, music is produced with dengbej artists and musicians, as well as movies and documentaries.

90% of the songs and videos dedicated to the revolution and which were produced in Rojava, are productions of Hûnergeha Welat. The name is in memory of the martyr Welat. This comrade was killed by a denotation of a car bomb from the so-called Islamic State. He was a very important friend, who kept himself busy with music and art and who knew a lot about the arts.

Hûnergeha Welat was a project, which we wanted to realize with him. Instead, we created the project and remembered him by naming it after him. The comrade Mehmûd Berazî is working at the moment on music. Likewise other friends, such as Kawa, Serxebên, Comerd, Ozan, Evan and many more. In the section of documentary film, the comrades Alab and Ali are the main contact persons. Of course there are many more members, who I didn’t name here but who are an essential part of our work.

Article by Komun Academy for Democratic Modernity – Some Rights Reserved

Video

Şervano Şêhîd Yusif Nebî’nin (Şivan Rohat)

Hunergeha Welat – Şervano

Related Articles

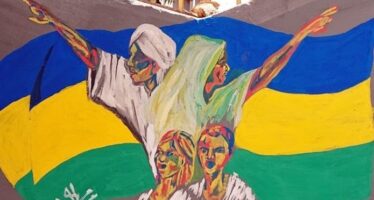

Against Erasure: Art and Sudan’s Sit-in

![]()

More than 100 people were killed and hundreds injured in the government’s June 3 attack on a sit-in in Khartoum

First Arabic Translation of Murray Bookchin’s work now available!

![]()

The ISE is thrilled to announce the first-ever translation of Murray Bookchin’s work into Arabic – “The Communalist Project”

Palestinian Poet Dareen Tatour Sentenced to 5 Months; Create Art To Help Fight Her Conviction

![]()

Dareen Tatour has already spent more than two years and eight months between prison and house arrest for “incitement to violence”