The book by YPJ commander Meryem Kobanê: A dream destroying borders

![]()

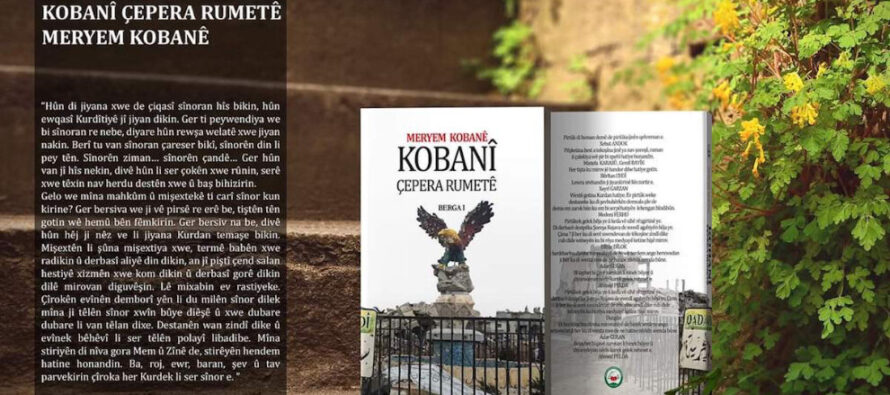

The first volume of the book of Meryem Kobanê, one of the commanders of the historical Kobanê war and victory, about those days, “Kobanê: Çepera Rûmetê” was published by Şilêr Publications.

The first volume of the book of Meryem Kobanê, one of the commanders of the historical Kobanê war and victory, about those days, “Kobanê: Çepera Rûmetê” was published by Şilêr Publications.

Translations in different European languages are already underway as this book is not only a beautiful piece of literature but also an important testimony and tribute to the resistance and victory carried out by men and women in Kobanê.

Meryem Kobanê is one of the witnesses of that time when ISIS destroyed cities one by one in 2014 and brought states to their knees. She is a protagonist and witness of the great resistance in Kobanê.

With the book “Kobanê: Çepera Rûmetê”, Meryem Kobanê brings together the will of a handful of revolutionaries who said “Kobanê will not fall”. She did this first by fighting, this time she does it as a story teller.

The book is also a very valuable recent history document.

From a border village of Serxet (North Kurdistan) to Binxet (Rojava Kurdistan), Meryem Kobanê looks at the borders that are dividing Kurdistan with the eyes of a child, pursuing her childhood dreams.

Meryem Kobane’s dream of crossing the borders as a child comes true in Kobanê, where, years later, a people stood hands in hands and destroyed those borders.

Meryem Kobanê, who held a gun in her hand during the Kobanê war, now undertakes the task of transferring that war, resistance, will and heroism to the new generations with a pen in her hand.

She spoke to ANF about the book and its importance.

With this book, you became the narrator of the historical Kobanê victory after being one of those who achieved this victory. What was your aim while writing this book?

Undoubtedly, the expectation to carry over and convey the truth of a war that you witnessed and fought bears a high responsibility. There are great resistances in the history of the Kurds. But most of them remained only oral. There are many different reasons for this, but since the result remained oral, most of those resistances do not somehow become history.

That is why a person who witnessed a great war like Kobanê, who witnessed many moments and took decisions there, has a responsibility to leave it to history. There was such a responsibility not only for that truth not to be lost but also for it to be passed on to new generations and history. We wanted the truth to be known. Yes, this was also the task of a militant of the freedom struggle. I wanted that the truth of the great war we fought be conveyed and be the legacy of the resistance history of all Kurdistan and other peoples. Every Kurd needs to know this truth. Because if a people does not know its past, it cannot build its future.

Your book starts with the border. You define the border from a child’s perspective. The border is one of the biggest traumas for Kurds…

Borders have always meant pain in human life. The first words and emotions that come to mind when talking about borders is: falling apart, being separated, expatriating, being exiled. Borders, not only in human life, but also in the life of all living things means obstacle. It means stopping the flow. Longing accumulates when there is no flow…

It is the biggest embarrassment of the world that our country is divided by borders. They tried to educate us Kurds with borders. Yes, they did that physically, but mentally and emotionally they could never succeed in making us accept those boundaries. Because it is impossible to put borders to thoughts and feelings.

This is why every child who has lived close to the border has a border metaphor in his/her eyes. When you come to a border, the first thing you feel is barbed wire. Those borders are never forgotten. But there is something else that those who build those boundaries do not take into account, or try to extend their life by denying them: the fact that borders always bring hatred and anger. This situation is also valid for us Kurds. Kurds have never accepted the borders drawn between Kurdistan. Every Kurd saw those borders as their denial and destruction.

Years later we see that girl on the North side of the border as a revolutionary on the other side, in Rojava. Could you tell us a little bit about your first feelings in the land of revolution?

I tried to express this in the book: What I found the most difficult thing to make sense of even in my childhood and which became an open wound for me in later years were borders. Tens of questions were constantly puzzling me, such as why the border, why these people cannot see each other, why is there a constant obstacle between us, why can’t we play games with our children on the other side, and we can only see them from a distance? There was no escape from these questions. As a child I started looking for answers to these questions. As I learned something, my consciousness of Kurdishness grew stronger and so did my hatred against those who drew those borders between us.

Pursuing the dream of childhood…

I remember well in my childhood I always dreamed of having wings. I dreamed that I could fly over the border, to see our relatives on the other side, to play with my cousins. In fact, our childhood games often were about crossing borders. I can say that the answer to the question of how can I cross that border never abandoned me. I followed my dreams. I saw my dreams indispensable. Sometimes I followed them, sometimes they followed me…

Years later, when I looked at the land where I was born this time from the other side of the border and dreamed of how to eliminate them, my dreams were with me again. But now, I realized that those borders could not be crossed by wings… You have to do something to make the borders disappear.

Because boundaries were the product of an imposition…

Yes, those borders were aimed at sowing genocide, hostility and contradiction among brothers and peoples. For example, my mother used to talk about Assyrians and they were no strangers to me. When I crossed to Binxet (Rojava), I also saw Syriacs there. This means that these borders shattered not only the Kurds, but also other peoples and beliefs. When I was a child, my mother used to tell not only the Kurdish çîrok (stories), but also Assyrian and Armenian çîrok. Then I began to grasp the real meaning of borders sowing hostility. Just as the story of the Assyrian girl Febrûniye which begins in a church in Nusaybin and ends with her death in a church in Qamishlo…

You are also the witnesses, decision makers and survivors of many of the events that you describe in your book. Was it difficult to put them on paper?

This is really a difficult issue. Surely, you experience many emotions at the same time while you are at war. It is a flood of emotions. But the most dominant feeling is ‘how do I win this war’. It is undoubtedly difficult to be in this flood of emotions, but really much harder to write about them. Because you are reliving many events that you have witnessed. You are also worried about not being able to do justice to the heroism experienced. One may be bolder or more assertive than the other, but ultimately there is also the truth that all hearts beat for victory. I made a lot of effort so that no one was left out of the book. Maybe not all of them have names, but they all joined with their skills to ensure that victory. I tried to write down those images that I saw with my eyes and recorded in my mind. When I first decided to write a book, my only goal was to be the language of those heroes. I wanted everyone to know these heroes. I wanted to be fair. I don’t know how much I have achieved it, but that was my goal. I made an effort so that no one is forgotten.

Let’s ask what was the most difficult thing while writing…

You know, as the great philosopher says, you can’t bathe twice in the same river. It is very difficult to live and feel a memory for the second time. Yes, the mind is also the place to record memories. But one should not forget the destruction of time. My biggest concern was not being able to do justice to the resistance and heroism I experienced. It was this anxiety that I struggled most with.

How does it feel to be both a freedom fighter and the narrator of a historical war, a historical period? Because the people you describe in the book are not “fictional heroes”, but the greatest heroes of the 21st century and you know them all…

We see ourselves as truth seekers, truth fighters. We are fighting for justice against injustice. We are fighting for rights against injustice. As the dominant system, capitalism is also waging a war against the memory of human and society daily, in fact every second. Truth seekers or fighters are also fighting against this system that targets the common memory of humans and society. Being the narrator of this great war is a completely different, indescribable feeling, of course… When we chatted between us sometimes while at war, we were making a promise to each other: whoever lived would write what happened and make it immortal. Indeed, I saw the greatest people, the most epic heroes in that war.

When I decided to write those historic days that were a source of hope for all the oppressed, I wrote it feeling that there was a great burden on my shoulders. There was a promise I had made. These experiences would not be forgotten, they would be written, left to history, passed on to new generations… Because writing was an order of the martyrs.

No one I am talking about in the book is a fictional novel or movie character. They are all real heroes. Children of this people. Each of them is the living hero of every village, street and city of Kurdistan. They are heroes who walked for a life of dignity, without blinking when faced with an honourable death. My heroes are the ones I saw, gunpowder coming out of the barrel of their gun, and the ones of whom I heard the roar of an empty stomach. They are my heroes …

Did you believe that you could one day tell what happened while fighting in Kobanê?

This book has a story of its own. One day, we were in the first group of friends that went to Kobanê and we were chatting. Kobanê was surrounded from all sides. We had not recorded much of what happened in the early years of the revolution. In that conversation, we said that whoever survived should write what happened. Before that, I had read the book The Unknown Soldier. It was then that I had decided that no fighters or resistance fighters should remain unknown in Kurdistan. Too many people wanted our country to remain unknown. Now, they wanted to silence those who resisted, struggled and fought for that country. As a matter of fact, there have been many fighters left unknown in our history.

While chatting with Heval Cûdî, Dilgeş, Roza, Masîro and Baharîn, we said that the last person left would write Kobanê’s resistance book. As in the story of the 300 Spartans, we were saying that someone should be saved. That survivor would bring tens of thousands with him. We believed it. Heval Cûdî always told me ‘write down about friends, what happened, the resistance’. He said, ‘You are traveling on all fronts, you know all your friends well. At that time, I was keeping a diary. Because we had a promise made to each other. Fulfilling it was a revolutionary task.

You said “Kobanê will be like Stalingrad” in an interview you gave during the heavier days of the war. Indeed, Kobanê did not fall as someone expected, and it became the 21st century Stalingrad for both Kurds and peoples. Looking back today, what would you say?

The answer to this question is in the second volume of the book. It was the first day of the attacks in September. It was around 1 or 2 pm in the village of Serzûrî in the east of Kobanê. The clashes were heavy. As they say, bullets were pouring like rain. At that time, that scene in the movie Stalingrad came to my mind. With that image in front of my eyes, I said, “This will be the Stalingrad of the Middle East. Just as Stalingrad did not allow fascism to pass, Kobanê will not allow ISIS.” Because there was no hesitation or fear in the voices of any of those 13 friends on the upper floor of the Serzûrî school. One day and night they resisted without hesitation. Their morale and their belief in great war was being renewed once again.

With your resistance in Kobanê, for the first time in Kurdish history, that traumatic borders were hit. The Turkish state initially tried to protect those borders by building walls around it. When this failed, it started invasion operations.

We started talking about borders, let’s end with borders. Instead of those wire fences, they built concrete walls so that we wouldn’t see each other. But these efforts are all futile… This must be said and seen: Kurds are not the old Kurds. The occupiers are still alien to Kurdish history. They said in Ağrı that “the imaginary Kurdistan became forgiven here we poured concrete on it”. But the Kurds shattered that concrete like a plane tree. No matter what they do, those borders are no longer holding. Because the Kurds removed the borders in their minds. If they draw a border around every house, every street, every village, they have no chance to be successful. Just as young women, old people and children will remove their borders, they will shatter their walls. The philosophy of leader Abdullah Ocalan once lifted the borders of the minds and hearts. What power can harm the heroic stories of the Kurds anymore?

Is there anything you want to add?

Let me state again that in fact, I did not write this book. This book was written by the fighters who destroyed those borders. This book is the work of people of all ages, tribes and beliefs from four parts of Kurdistan, from Europe, the Middle East and different parts of the world, who have joined the resistance and whose hearts beat with the resisters. I offer my infinite respect and love to all of them. Once again, I remember the martyrs with respect and gratitude.

Related Articles

La guerra olvidada del pueblo Saharaui: Entrevista con Kristina Berasain

![]()

Kristina Berasain Tristan, periodista vasca especializada en conflictos olvidados y derechos humanos, ha sido durante años responsable de la sección internacional del periódico Berria.

Families of Er and Dağ appeal to international community

![]()

Abdurrahman Er and Mazlum Dağ were sentenced to death on 11 February 2020 by the Second Hall of the Erbil Criminal Court in the Autonomous Region of Iraqi Kurdistan – governed by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). The sentence was confirmed by the Court of Appeal on 22 September 2020.

Foza Yûsif: ENKS imposes unacceptable demands

![]()

PYD Co-Presidency Council member Foza Yûsif said that there is a deadlock in the talks on unity in Rojava, and