Suspicions Destroyed Lives of Victims’ Relatives

![]()

Neo-Nazi Terror Cell

Ufuk Ucta/ DER SPIEGEL

They said that their father was sick, that he had had an argument with customers and was now in the hospital. Semiya Simsek didn’t believe the relatives. Her father was a nice man and never argued with anyone. Besides, she said, her father was also a strong man, and he was never sick.

Simsek remembers the day, when, at the age of 14, she wandered through the hallways of a Nuremberg hospital in search of her father, who was in the intensive care unit. He was unconscious after having been shot in the head by two strangers a few hours earlier. A police officer detained Simsek, telling her that she could not see her father at the moment, and that she would have to answer some questions first. “Was your father threatened?” he asked. “Did he own any weapons?” Simsek shook her head. He had a knife to cut flowers, she said, and he had never had any enemies.

Meanwhile Adile Simsek, Semiya’s mother, was being questioned for several hours at a police station. The officers wanted to know whether she had had an argument with her husband, and whether she knew anything about a possible affair. The women broke out in tears. Her husband was dying, but the police officers refused to let her see him because they suspected her of murder. They claimed she and an uncle had shot her husband out of greed — she, of all people, who had spent her entire life at the side of this man, who still loved him as much as she did when they first met in a village in southern Turkey.

‘All of You Declared Us Guilty’

Semiya Simsek, who is now a young woman, is sitting in the kitchen of her apartment in Friedberg, a town north of Frankfurt. Eleven years have passed since her father was executed. It also took 11 years until the police accidentally hit upon the real killers, five weeks ago. The wife hadn’t killed him after all, nor was it a Turkish drug dealer, as the police speculated for a time. Enver Simsek, a florist and the father of two children, 38 at the time of his death, became the victim of a gang of neo-Nazi killers on Sept. 9, 2000.

For years, the far-right terrorists Uwe Böhnhardt and Uwe Mundlos went on a killing spree around Germany and managed to elude the authorities. Enver Simsek was their first victim. Nine others followed before the two neo-Nazis took their own lives on Nov. 4, 2011. Germany has learned a lot about the killers since then, but too little about their victims.

Semiya Simsek’s hands are shaking. “All of you — the police, the media, society — declared us guilty,” she says. The police treated Semiya’s mother as a suspect for a year and a half. They questioned neighbors and relatives. The victim’s parents, suspicious of their daughter-in-law, severed ties with the family.

Two other Turks were murdered in June 2001, one in Nuremberg and one in Hamburg. They were shot with a Ceska pistol, the same type of weapon used in the first attack, leading investigators to conclude that the murders had to be connected. They speculated that other members of the Turkish immigrant community might have committed the killings.

The police searched the Simseks’ apartment for weapons. Enver Simsek had bought flowers in the Netherlands every week. Suspecting that this could have been a cover for smuggling drugs, the police brought in tracking dogs. The neighbors began whispering about the Simseks. At school, Semiya was accused of being the daughter of a drug dealer. “The police have no idea what they did to my family,” she says today.

There was little reason to suspect any connection between some of the victims and the Turkish underworld. Did the investigators allow themselves to be influenced by prejudices about Turkish immigrants? Many media organizations, including SPIEGEL, suspected that Turkish criminals were behind the killings.

If Germans are under the impression that Turks are such a barbaric people that they would simply go around murdering each other, and that they would even do so over as little as a döner shop or a drug deal as a matter of course, this prejudice is far more dangerous than any racist terrorist, says Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu in a SPIEGEL interview.

Black Spot on the Floor

Ali Tasköprü was in Turkey, at his mother’s deathbed, when the long-awaited news arrived: It was neo-Nazis who had killed his son Süleyman in a Hamburg greengrocer’s shop on June 27, 2001. It happened 10 years ago, and now he knew the truth. But when he heard the news, everything came rushing back: how the family had tried to defend itself against rumors and how it had lived under a dark shadow for so long. Now the shadow was finally lifting. It was the neo-Nazis. When Tasköprü told his mother the news, she smiled — and died two hours later.

The three shots that killed Süleyman destroyed Ali’s life, permeating it with mistrust, fear and disappointment. On the day of the murder, a policeman on patrol came into the shop. He drank a cup of coffee with Süleyman and then told him that he had to move his car, which was in a no-parking zone. The father, who had to run a few errands for the shop, left in the car and was gone for 20 or 30 minutes.

There was a black spot on the floor when he returned. Perhaps, he thought, a jar had fallen down and the contents leaked on the floor. Then he saw Süleyman and realized that the black spot was a pool of blood. Tasköprü pressed his son to his chest. Süleyman was still alive and tried to say something to his father, but he could no longer speak. He died a short time later, at the age of 31.

Tasköprü was in a state of shock, and yet he was taken to the police station immediately and questioned for hours. Later on, the officers wanted to know whether his son had been involved in criminal activities. Tasköprü felt doubly victimized. First he had lost his son, and now the family honor was being dragged through the mud.

Other Turks, including good friends of the family, kept asking questions. Perhaps Süleyman was involved in something, after all, they said, because it was in all the papers. Eventually Tasköprü had had enough and broke off the friendships. “These people never believed me,” he says today. “For that reason, I will never sit at a table with them again, and I will never speak with them again, either.”

The revelations about the neo-Nazi murders have created new suspicions. “There are so many unanswered questions,” says Semiya Simsek, the daughter of the first victim. When she called the Federal Criminal Police Office for more information, she was told to read the newspaper.

‘We Felt Like Criminals’

The Federal Office of Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance has at least promised the families psychological counseling. Simsek, who works as a teacher in Frankfurt, plans to move to Turkey in the summer to join her mother there. She says that she no longer feels comfortable in Germany. Although acquaintances have already apologized for suspecting the family, she says that there are few people with whom she can talk about her feelings.

She is often on the phone with Gamze Kubasik, a pharmacy student from Dortmund in western Germany. The two women hardly know each other, but there is one thing they have in common: Kubasik’s father Mehmet was also murdered by the Zwickau neo-Nazis. And she too had to live with false accusations for years. Kubasik was questioned for eight or nine hours on the day after the murder. She and her siblings were fingerprinted and their saliva samples were taken. “We felt like criminals,” she says.

Her mother Elif, who lives in the same building as her daughter, still hasn’t overcome the tragedy that descended on the family. Since the images of the real murderers began appearing on television, she has only been able to sleep with the help of sleeping pills. She tries to take her mind off things by cleaning the apartment — constantly. She scrubs the floor and polishes the lamps. But she cannot wipe away her dark thoughts as if they were dust.

She believes that her husband would still be alive if the police had only investigated the radical right-wing groups more thoroughly. “Germany killed my husband,” she says.

REPORTED BY ANDREA BRANDT, JÜRGEN DAHLKAMP, MAXIMILIAN POPP AND UFUK UCTA

Translated from the German by Christopher Sultan

Related Articles

La resistencia saharaui al otro lado de la frontera

![]()

Jaida Ihazaza espera noticias de su hijo desaparecido hace cinco años. / FOTO: Alberto G. Palomo. Cientos de saharauis

Young prisoner Berivan awarded in Sweden

![]()

The arrested fifteen-year-old girl’s family was honored by the Swedish Committee of Human Rights Association of Europe as a symbol

Exit poll shows Fine Gael/Labour govt has been ousted

![]()

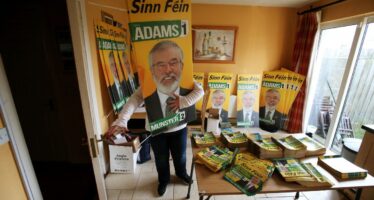

An exit poll of Ireland’s general election carried out by the Irish Times indicates no possibility of a return to government for the current Fine Gael/Labour coalition