‘The Bride of Reeds’ and Tamazight Literature’s from Oral to Written

![]()

Rachid Bouxerroub was the inaugural winner of the Assia Djebar fiction prize in the Tamazight category. Nadia Ghanem talks to Bouxerroub and discusses his winning novel, The Bride of Reeds: By Nadia Ghanem

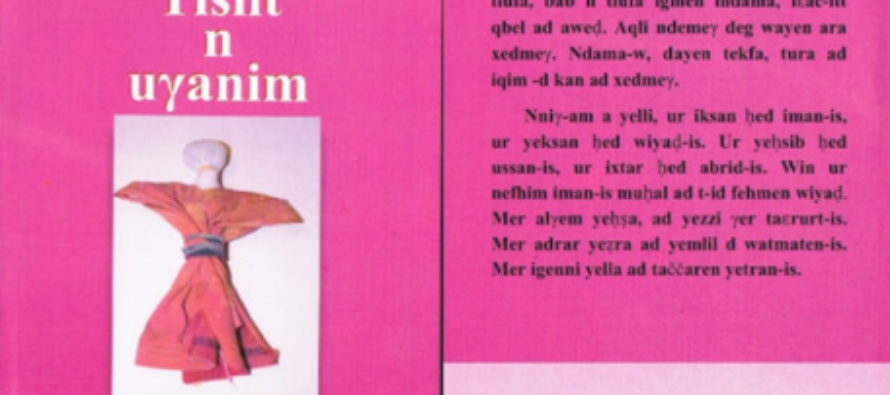

https://arablit.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/bride.png Tislit n’oughanim, El Amel editions, 2015, 157 pages, 250DA.

Last fall, Algerian novelist Rachid Bouxerroub won the Assia Djebar prize for Best Fiction in Tamazight for his novel Tislit n’oughanim (The Bride of Reeds).

The Bride of Reeds is a reference to the small puppet-like toys young girls make from little reed sticks, dress up, and play the bride.

Bouxerroub says the name seemed fitting for a story he centred around Fafuc [pronounced Fafush], a young woman in post-independence Algeria who had no control over her own destiny, like an inanimate doll, until she rebelled.

At the time of the prize, November 2015, Tamazight had not yet been declared “official” by the state — that constitutional amendment came in January 2016. If these languages’ new status has one effect, it will be to ease the production of literature in Tamazight, and new structures like the soon-to-come Tamazight Academy might even support this.

When I met with Bouxerroub and asked what the Assia Djebar prize had concretely changed for him, he said that “winning the Assia Djebar prize was very important. Being linked to the name of such a significant literary figure was wonderful, and on a personal level it motivated me to pursue writing. Concretely, I now have easier access to publishing houses and the media, and I have secured the means to publish my second novel next April. Tislit n’oughanim will also be translated into French and Arabic, this will give the novel a national dimension, and as an author, I will reach a wider audience.”

Algeria is a nation of polyglots. Aside the chaos created by the mismanagement of the nation’s linguistic assets, for literature it means that domestic translation for national consumption is very much sought after. Many authors, the well- and the lesser-known, have been and are translated by Algerian publishing houses from Arabic to French, French to Arabic, and Tamazight to French and Arabic. A multilingual dance both ancient and current.

The Bride of Reeds

In Tislit n’oughanim, the majority of characters are women, it is they who narrate the story. This situation echoes rural Algeria post war of independence when most men were absent, injured or had been killed.

Fafuc begins a life like that of a reed doll: she is orphaned of both mother and father, and has little other choice than to follow the rules ordering village life. It is when she is ousted from her husband’s home and forced to abandon her son that she becomes determined to reclaim the most basic human agency.

Who were the women who inspired Bouxerroub?

“First, it was my mother, may she rest in peace. Secondly it was the situation of Kabyle women in rural Algeria just post-independence. The majority of women at that time were widowed; they saw all manner of misery, and suffered from the harshest of socio-economic and socio-cultural conditions.”

Throughout this story set in ’70s in a small village, then later in the city of Tizi Ouzou, making characters cross into urban scapes, Fafuc denounces many abuses (arranged marriages, confinement, social violence). When asked how natural it was, or not, to speak in the voice of a woman, Bouxerroub said, “I think it is very natural to speak as such. I lived through and felt the intensity of my mother’s suffering, of my sisters and of all the women of our village. Today, through this novel I feel I have released all the hurt my mother experienced, something she couldn’t do herself in the past because of the constraints of morals and traditions. The origin of my inspiration is both experience and reality. I was a child during ’70s; I used to have an elephant’s memory and I’ve kept an enormous amount of memories from that period.”

In this novel, which is his first, Bouxerroub alternates between a fluid narration and dialogues almost poetic, the rhythm and musicality of which echo Kabyle story telling. Was it the result of Tamazight’s own magic or did he particularly work on his text?

“Everything was spontaneous, I did not work or study anything. I wrote the text as it came. This style corresponds to and matches the theme of my novel. When emotions are strong, we become poets and artists without paying attention.”

It’s an interesting remark in light of orality’s influence on this new space, a written and fixed space, attempting to emerge as a new mode of transmission. In that respect, Tislit n’oughanim strongly resembles timucuha [Berber oral stories] in places. Timucuha are a type of tales that resemble both wisdom literature and poetry and which Bouxerroub continues to tell his children: “Yes, and many of them like Lunja n teryell [Lundja and the Ogress], Xettaf la?rayes [Marriage Kidnapper], a?qa yessawalan [The Magic Grain].

From an oral to a written language

One of the most fascinating and exiting aspects of the development of Tamazight since the first cultural activists took charge of its protection is its change in status from an oral language to a written one, a process initiated several decades ago which continues taking shape. This change, which aims in part to place Tamazight on a contemporary map of written languages, is also an attempt at a historical recovery based — loosely at times — on the written evidence of inscriptions in Tifinagh, Tamazight’s very own ancient script.

Oral transmission remains the norm for Tamazight-language speakers, but the consolidation of these languages as written is steadily being given tools and growing more solid. Early militants began structuring this development by working on choosing a script and an alphabet, as a rallying sign for unity, and the canonization of a narration of Berber history. They collected folktales, produced grammars, revived vocabulary with works on neologisms, and pushed for an independent historical timeline.

The next generation supplemented these efforts with the creation of bilingual dictionaries (Tamazight-French, and Tamazight-Arabic), with scholarly studies of the languages’ variety and morphology. Tamazight has been taught in schools since 1995, when it was made part of the national curriculum. School manuals were conceived and have been used since to teach a form of Tamazight they pass for a standard ancient form — a most curious version indeed, but no matter, a birth is rarely immaculate.

Why write in Tamazight?

“Kabyle is my mother tongue and it is the langue in which I can best express my feelings. I also feel that I owe this language a debt,”

Bouxerroub says.

Before parting, I ask him what future he hopes and wishes for literature in Tamazight, he says that “in order for Tamazight culture to move forward, we must produce. I hope that our culture will finally take its rightful place in a universal context.”

https://arablit.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/nadia.jpg&h=81 Nadia is ArabLit’s Algeria Editor and a doctoral student at the School of Oriental and African Studies, where she specializes in the ancient languages of Iraq and Syria. Based between Algeria and the UK, she blogs at tellemchaho.blogspot.co.uk ( http://tellemchaho.blogspot.co.uk/ ) about living in Algeria, and Algerian literature.

Related Articles

Google launches data ‘graveyard’ option

![]()

Internet search giant introduces option that allows users to determine how their online material is used after death. New

WikiLeaks cables claim al-Jazeera changed coverage to suit Qatari foreign policy

![]()

US embassy memos flatly contradict Arabic satellite channel’s insistence that it is editorially independent despite being heavily subsidised by Gulf

The Language Wound – Bilingualism with Kurdish

![]()

“The Language Wound: The use of the mother tongue in education and experiences of Kurdish students”, a study from the