Roma return home and lament end of dreams of a better life in France

![]()

Roma return home and lament end of dreams of a better life in France

‘We had little in France, but we have nothing in Romania’, say Gypsy families forced from their adopted home

Lizzy Davies in Barbulesti

On the approach to Barbulesti the highway dissolves into gravel and dust. For Romica Raducanu the village in which he was born and brought up feels like the end of the world. His hopes of a new life are for now a distant dream and he is stuck here. Only his T-shirt gives away the place he considers home: emblazoned over stripes red, white and blue is one word – France.

Until three weeks ago Raducanu was living on the outskirts of Montpellier in southern France, eking out a living for his wife and children by collecting scrap metal and selling it on for seven centimes (6p) a kilo. Then, after a summer of growing unease, the crackdown ordered by President Nicolas Sarkozy hit home. Friends were ordered to leave, and the pictures he was seeing in the newspapers became too much. Raducanu was scared.

Without taking the money available to him as part of the “voluntary repatriation” scheme – he didn’t understand the papers, he says, so he didn’t sign them – the 35-year-old and his wife packed their family into the car and set out, with other departing Roma, on the journey of more than 1,000 miles to Romania.

A day later he heard that the police had come to clear away his former home. Now, in the dilapidated surrounds of his new one, he is bitter and depressed.

“We had to leave so that we weren’t sent away. Every day I was seeing in the papers and on the television that more and more people were being expelled,” he says quietly, fiddling with the handle of a bedroom door missing half a pane of glass. Remembering the moment he realised what was going on, he adds: “We were desperate when we heard. Sarkozy hates the Roma. He’s making the same moves as Hitler.”

Vichy comparison

An extreme comment in the same vein provoked fury this week in the Elysée palace, where the French president fumed over the comparisons made by Viviane Reding, European commissioner for justice, between his summer clampdown and persecution of the Jews during the second world war.

But, incendiary as these remarks may be, the vehemence of Raducanu’s anger is perhaps understandable. For, he says, while he had little in France, he has nothing in Barbulesti.

Since the end of July, when Sarkozy made a speech in Grenoble outlining his tough new approach on crime and immigration –the two themes, he implied, were inextricably linked – about 1,000 foreign Roma have left France, mostly for Romania and mostly under a scheme offering €300 (£250) for each adult and €100 for each child returning to their native country.

About 200 non-authorised Roma camps have been cleared, as well as hundreds of traveller sites occupied mostly by French citizens. However, a leaked circular, since amended to avoid singling out an ethnicity, stated that the Roma were the chief targets of the evacuations.

For many French people and other western Europeans who witness the poverty in which a large number of Roma live, in cities from Marseille to Milan to Madrid, their desire to stay is incomprehensible.

Yet most of the 7,500 Roma in Barbulesti, a predominantly Gypsy village 50 miles north-east of Bucharest, say that a life in the wealthy west offers chances unimaginable in their native Romania, where the vast majority are trapped in a cycle of discrimination, unemployment and poverty.

And, as long as this remains the case, they say, they have no intention of staying put. Ever a nomadic people, they will be on the move again soon.

Raducanu, an EU citizen entirely conscious of his right to free movement within the bloc, is already planning his return. “I can’t wait to get back, to work. There is nothing to do here. Hunger. No work. I will go back,” he says. Later, in a flourish of the language he had learned to love, he adds: “C’est très dur, la vie.” Life is very hard.

Appearances

At first sight, it is difficult to understand why Raducanu and his fellow villagers feel this way. With its large, villa-like houses in bright shades of reds, oranges and greens, Barbulesti looks from far off like a Disneyesque hamlet rising from the acres of flat, drab Romanian scrubland. Children wander, rucksacks on their backs, home from school; many roofs have satellite dishes and expensive cars are parked in driveways.

Compared with some of the Roma squats in France, these homes appear salubrious.

Appearances, however, can be deceptive. In one house in the centre of the village carved lion heads sit proudly atop wrought-iron gates and the back garden is shaded from the sun by trellises threaded with vines.

But, inside, the reality of living standards becomes clear. The villa is clean and tidy- but its four rooms are home to four families. “Seven people live in here,” says Stylian, a 34-year-old man who did not want his surname to be published. “And six in here.”

Throughout the house, open wires run precariously over ceilings and walls, and the cheer of paint in electric pink and lime green cannot mask the fact that the mud walls and wattle-and-daub roofs are badly in need of repair. The kitchen, used to feed more than 20 people, is open to the stony ground, and the fridge is virtually bare.

A decades-old well brings up water, and the single toilet is a hole in the ground in an outhouse. “We wash it, we keep it clean,” says Stylian. As he speaks, children play on the rusting hulk of a climbing frame next to a pig sty. The pigs are long gone.

A gruff but genial man, Stylian is another recent arrival in the village from France, where he had been living near the Belgian border on and off since 2002. He repeatedly dodges questions about how he managed to earn enough to support his wife and children; it is admitted that many residents end up begging or working in illegal activities.

But he insists his lack of success was not due to a lack of effort: he tried everything in his power to work legally, he says, but to no avail.

One opportunity as an apple-picker proved particularly elusive. “The paperwork remained in the prefecture, the apples remained in the tree, and we left,” he jokes.

When asked about the trigger for his return a fortnight ago, however, Stylian’s smile vanishes and his voice begins to boom around the driveway. “I don’t agree with these [forced or voluntary] returns. It’s racism,” he says, describing how, frightened by the political climate and police threats of expulsion, he eventually left of his own accord.

Before Sarkozy, he says, there was less prejudice against the Roma in France than in Romania. “But now they’re both the same.” Were it not for the fact that, at home, “you can work all day and not make enough to eat”, he says, there would be no reason to go anywhere else. “Nobody would leave then. Who wants to leave their home?”

In a statement earlier this year, the human rights group Amnesty International issued an urgent appeal, warning that the authorities must stop their “forced evictions” of Roma people and “immediately relocate” those living in “hazardous conditions” on the margins of society.

After a summer in which the plight of France’s estimated foreign Roma, estimated to number between 15,000 and 20,000, came under the spotlight as never before, those words are all-too familiar.

However, the plea was not directed at Paris, but at Bucharest, and the living conditions described were not those of foreigners in a strange land but of Romanian citizens in Romania.

“Across the country Roma families are being evicted from their homes against their will. When this happens, they don’t just lose their homes. They lose their possessions, their social contacts, their access to work and state services,” said Halya Gowan, Amnesty’s Europe and central Asia programme director, in the January appeal.

With unofficial estimates pinning the number of Roma in Romania at 2.2 million, the minority makes up about 10% of the country’s total population. Yet, say human rights groups, the Roma are routinely ignored and pushed out of the mainstream, their needs not met and their voice not heard.

According to Amnesty, endemic prejudice leads to discrimination from the authorities as well as society at large, while the statistics speak for themselves: 75% of Roma live in poverty, compared with 24% of Romanians and 20% of ethnic Hungarians. Unemployment is far higher than the norm, and life expectancy is significantly lower.

For all these reasons – not to mention the economic ties that have deepened since EU accession in 2007 – the Romanian government has been careful in its reaction to the Sarkozy crackdown. As the French have repeatedly pointed out, Bucharest is in no position to judge: if it weren’t for its failure to integrate the Roma, they argue, the “problem” would not be so acute elsewhere in Europe.

Mild rebuke

But, behind the relatively mild diplomatic rebuke issued by President Traian Basescu, who, though telling France he “understands” its position, insists Romanians have the right “to travel without restrictions within the European Union”, there is considerable anger.

“It’s obviously a discriminatory position. It is not normal to expel people collectively,” says Ilie Dinca, head of the National Agency for the Roma (ANR), a government body set up to try to secure funding for Roma-related projects. He is impressed, he says, with the “belated but good” line taken by Reding this week. The commissioner has since apologised for the delay.

And, in a reflection of the confusion expressed by many people in Barbulesti, he adds that he has “a big question mark over the paperwork” returning Roma had been asked to sign in France relating to the “voluntary repatriation” schemes. “Because they weren’t given a copy of what they signed,” Dinca says.

The ANR is at the forefront of government efforts to solve the Roma problem. In the past decade a number of projects designed to facilitate integration and boost living standards have emerged, from the appointment of special health and education “mediators” designed to communicate on behalf of the Roma, to positive discrimination measures in Romanian high schools.

On top of the €22m received from the state, Dinca says, €90m comes from Brussels to go towards various NGOs and Roma-related institutions.

And yet no one – in Bucharest, Brussels, or least of all Barbulesti – believes it is making a lot of difference.

For Viorel-Vivari Banescu, a teacher at a mainstream Romanian school near Barbulesti, the one thing that could change things is education. The most important thing the state can do, he says, is provide retraining opportunities for adult Roma and classes for their children. “They have a tendency to self-victimise, to say ‘I don’t have a job because I’m a Gypsy,'” he says. “But that’s not true. He doesn’t have a job because he doesn’t have any training.”

Pacing the ground in the town, Banescu tries to recruit 14-year-old Posirca Marian, who has been skipping class, a common problem in the local school, which has the county’s biggest number of pupils on paper but in practice sees high absenteeism.

Parents receive €10 from the state for every child they have in school, but often say they still can’t afford the kit required for attendance. “I want to make him my champion and get him through the 7th and 8th grade,” says the teacher.

Over in the Raducanu family’s backyard, lines of tiny socks and vests hang out to dry in the sun, and indoors Romica’s wife, Simona-Mariana, struggles with the couple’s restless brood of toddlers. They are a family of nine living in a two-room house with no proper kitchen.

As he strides up to the paint-chipped door, the village’s vice-mayor, Lita Vasile, snatches a pear out of the mouth of five-year-old Jacob. It is half-rotten. “This is what we’re eating,” he exclaims, brandishing the fruit in his hand. “Sarkozy should think about the basic rights. His [Raducanu’s] kids have nothing to eat today.”

Unlike many of his more bombastic, heavyset friends, Raducanu is a slight young man who speaks quietly, in both French and Romanian, of the “great” people of Montpellier, of the “respectful” French police, and his life there, where, in the embodiment of Sarkozy’s work ethic, he “got up early and even worked Sundays”.

He can provide more for his family there than here, he says, as squeals come through the bedroom window. What are his hopes for the future? “That I will get back to France, to give them something.”

Related Articles

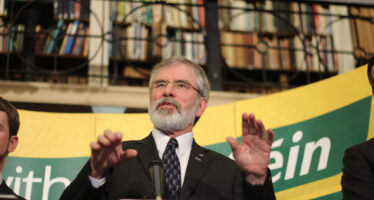

Standing up for Ireland in the EU

![]()

Earlier this year an opinion poll found that 44 per cent of people in Britain were proud of its history of colonialism while only 21 per cent regretted that it happened

Iranian Teenager Facing Execution

![]()

IRANIAN TEENAGER FACING EXECUTIONJuvenile offender Ebrahim Hamidi, now aged 18, has been sentenced to death for allegedly sexually assaulting a

Socialist Irish TD and five activists found not guilty in water-charges protest trial

![]()

Socialist Paul Murphy TD and five other men have been found not guilty of falsely imprisoning former Tanaiste Joan Burton and her adviser during a 2014 water charges protest