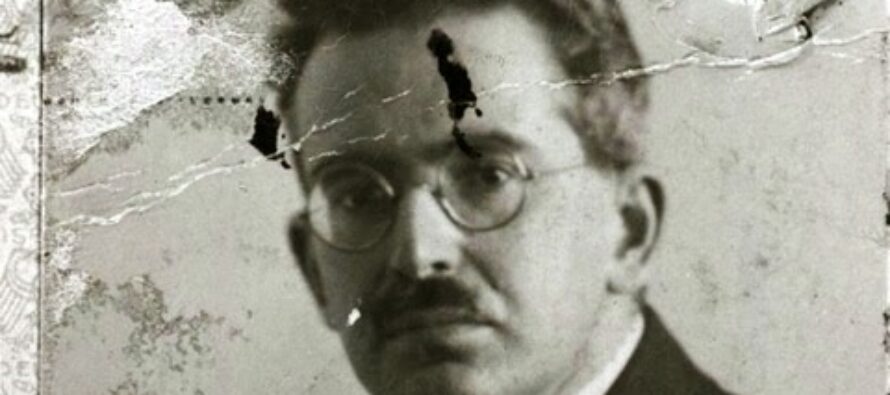

ON A DAY THIS WEEK… WALTER BENJAMIN

![]()

ON A DAY THIS WEEK …

ON A DAY THIS WEEK, in September, 1940

Seamas Carraher

On a day this week, the 26th (or 27th) of September, 1940, and maybe early in the morning, certainly in his hotel room in the Hotel de Francia,

in the village of Portbou, on the French-Catalonian (Spanish) border, the radical German Jewish intellectual, Marxist, and writer Walter Benjamin died by suicide after almost a decade fleeing the Nazis and on threat of being handed over to the Gestapo by Spanish border guards the following day…He was just 48 years old.

In his last written work, Theses on the Philosophy of History (Über den Begriff der Geschichte) Benjamin quotes a poem by his friend Gerhard (Gershom) Scholem, the German born Israeli philosopher who wrote:

“Mein Flügel ist zum Schwung bereit,

ich kehrte gern zurück

denn blieb ich auch lebendige Zeit,

ich hätte wenig Glück.”

“My wing is ready to fly

I would rather turn back

For had I stayed mortal time

I would have had little luck.”

Gerhard Scholem,

“Angelic Greetings”

He goes on to describe Klee’s Angelus Novus and his own Angel of History that would pursue him for the rest of his short life:

There is a painting by Klee called Angelus Novus. An angel is depicted there who looks as though he were about to distance himself from something which he is staring at. His eyes are opened wide, his mouth stands open and his wings are outstretched. The Angel of History must look just so. His face is turned towards the past. Where we see the appearance of a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe, which unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble and hurls it before his feet. He would like to pause for a moment so fair [verweilen: a reference to Goethe’s Faust], to awaken the dead and to piece together what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise, it has caught itself up in his wings and is so strong that the Angel can no longer close them. The storm drives him irresistibly into the future, to which his back is turned, while the rubble-heap before him grows sky-high. That which we call progress, is this storm. (Theses on the Philosophy of History – Über den Begriff der Geschichte, Thesis IX)

Born in Berlin on July 15, 1892, 3 years before his brother Georg (born in 1895 and to die on 26 August, 1942 in the Nazi Concentration Camp at Mauthausen) and his sister Dora, born in 1901. His father’s business ventures being successful Benjamin’s early years were nurtured by the privileges of an upper-middle-class childhood including the services of a governess.

This situation was not to last as Benjamin was to spend the greater part of his adult life in poverty, a consequence of his commitment to the work of writing, as Hannah Arendt said: “No one, of course, (was) prepared to subsidize him in the only “position” for which he was born, that of an homme de lettres, a position of whose unique prospects neither the Zionists nor the Marxists were, or could have been, aware.”

Walter Benjamin: “The poor—for the rich children of my age they existed only as beggars. And it was a great advance in my understanding when for the first time poverty dawned on me in the ignominy of poorly paid work” [Schriften I, 632]

By 1912, shortly before the start of the ‘First World War’ and at the age of 20, Benjamin had begun his fragmented university career at the Albert Ludwigs University in Freiburg im Breisgau “in order to study philosophy”. Freiburg was to offer him little. He soon returns to Berlin, enrolling in the Royal Wilhelm Friedrich University there. He attends lectures by “Ernst Cassirer, a neo-Kantian best known for his philosophy of symbolic forms, Benno Erdmann, also a Kantian philosopher, Adolph Goldschmidt, the German art critic and historian, Max Erdman, a leading Kantian scholar, and the social and economics philosopher Georg Simmel.” In the spring of 1913 he returns to Freiburg for the summer semester where he attends lectures given by the neo-Kantian philosopher Heinrich Rickert.

His dissatisfaction with his early encounters in philosophy were to shape his unique approach to thought and critical theory in general.

It is also around this period (August 1912) that he comes in contact with Zionism which will be encouraged by his lifelong friendship with Gershom Scholem: “With Scholem, Benjamin again experiences the pull of Zionism and his Jewish identity, topics on which they frequently converse”. The relationship with Scholem, beginning in July 1915 in the library of the University of Berlin “…would have a lifelong influence upon Benjamin’s relation to Judaism and Kabbalism, notably in his interpretations of Kafka in the early 1930s and in the messianic interpretation of the Paul Klee painting Angelus Novus in his later theses ‘On the Concept of History’.” However Benjamin’s interest in Zionism would be cultural as opposed to the nationalist or political version. “Nevertheless Scholem would prove instrumental in establishing and, in part, shaping the legacy of Benjamin’s works after his death.” (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

In the interim Benjamin avoids involvement in the murderous First World War, faking illness (initially from palsy) in order to avoid conscription. He is successful and receives a year’s deferment. He will be called up twice again and both times, through faking illness, will be lucky enough to avoid mobilisation and able to continue with his attempt to consolidate an academic career.

Before the end of both war and empire and the brief upsurge of the militant Left in the failed German revolutions of 1919-1921, in the fall of 1917 he enrolls at the University of Bern in order to undertake a doctoral dissertation. The subject of his dissertation is the philosophical basis of the theory of criticism developed within German Romanticism”. ‘The Concept of Art Criticism in German Romanticism’, was awarded summa cum laude, by the Swiss University, in 1919.

1921, Benjamin publishes his essay Kritik der Gewalt (The Critique of Violence) exploring the relationship between justice and violence in the context of human meaning. (“The task of a critique of violence can be summarized as that of expounding its relation to law and justice.”)

Walter Benjamin: “For the function of violence in lawmaking is twofold, in the sense that lawmaking pursues as its end, with violence as the means, what is to be established as law, but at the moment of instatement does not dismiss violence; rather, at this very moment of lawmaking, it specifically establishes as law not an end

unalloyed by violence but one necessarily and intimately bound to it, under the title of power. Lawmaking is powermaking, assumption of power, and to that extent an immediate manifestation of violence. Justice is the principle of all divine endmaking, power the principle of all mythic lawmaking.”

The Task of the Translator also comes from this period, 1921, (“No poem is intended for the reader, no picture for the beholder, no symphony for the audience…”)

Walter Benjamin:

“The concept of life is given its due only if everything that has a history of its own, and is not merely the setting for history, is credited with life. In the final analysis, the range of life must be determined by the standpoint of history rather than that of nature, least of all by such tenuous factors as sensation and soul. The philosopher’s task consists in comprehending all of natural life through the more encompassing life of history. And indeed, isn’t the afterlife of works of art far easier to recognize than that of living creatures?” (The Task of the Translator)

In 1924 Hugo von Hofmannsthal, in the Neue Deutsche Beiträge magazine, publishes Goethes Wahlverwandtschaften (Elective Affinities), about Goethe’s third novel, Die Wahlverwandtschaften (1809). “Where the presence of truth should be possible, it can be possible solely under the condition of the recognition of myth—that is, the recognition of its crushing indifference to truth.” Benjamin was to write…

Later in 1924 Benjamin and Ernst Bloch stay on the Italian island of Capri where Benjamin writes Ursprung des deutschen Trauerspiels (The Origin of German Tragic Drama), as a habilitation dissertation meant to qualify him as a tenured university professor in Germany. He also met the Latvian Bolshevik and actress Asja L?cis, then living in Moscow with whom he became emotionally involved and who was to be a lasting intellectual influence upon him. Both Bloch and L?cis introduce him to radical left-wing politics, and in particular the work of the Hungarian Marxist critic Georg Lukács, specifically his seminal work: ‘History and Class Consciousness’: (“Orthodox Marxism…is the scientific conviction that dialectical materialism is the road to truth and that its methods can be developed, expanded and deepened only along the lines laid down by its founders.”) At the same time, Benjamin also begins his own study of Marx’s writings. At the end of 1924, he summarizes this change in a letter to his friend Scholem:

Walter Benjamin: “I hope some day the Communist signals will come through to you more clearly than they did from Capri. At first, they were indications of a change that awakened in me the will not to mask certain actual and political elements of my ideas in the old Franconian way I did before, but also to develop them by experimenting and taking extreme measures. This of course means that the literary exegesis of German literature will now take a back seat.”

Luckily so, as his thesis on Baroque drama, submitted early in 1925 to Hans Cornelius, in the University of Frankfurt (among whose students were Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno) is unsuccessful in providing him with an academic career. “Cornelius declares that he is unable to understand it and passes the thesis to two colleagues who have the same response (one of these two colleagues is Max Horkheimer who, with Adorno, is a founding figure of the Frankfurt School and later becomes, in the 1930s, a friend and correspondent of Benjamin)”.

Wikipedia goes on to tell us that a year later, in 1925, Benjamin withdrew The Origin of German Tragic Drama as his possible qualification for the habilitation teaching credential at the University at Frankfurt am Main, fearing its eventual rejection. Thus ends Benjamin’s protracted and uncomfortable relationship with academic criticism and the university. He was not to be an academic instructor…(three years later, in 1928, The Origin of German Tragic Drama was published as a book). From this point on and despite ongoing criticism from the Frankfurt School, his insights will be forced to seek wider significance than that of the narrow world of academics and ‘professional’ intellectuals. This process will culminate and possibly find its conclusion in his last work, written early in 1940, the Theses on the Philosophy of History – Über den Begriff der Geschichte.

Walter Benjamin: (Theses on the Philosophy of History – Über den Begriff der Geschichte)

“The true picture of the past whizzes by. Only as a picture, which flashes its final farewell in the moment of its recognizability, is the past to be held fast. “The truth will not run away from us” – this remark by Gottfried Keller denotes the exact place where historical materialism breaks through historicism’s picture of history. For it is an irretrievable picture of the past, which threatens to disappear with every present, which does not recognize itself as meant in it.” – Thesis V

Benjamin’s lack of success in his academic pursuits, is a situation that will occur over and over in the course of his life, as if fated always to be unlucky, as the “political theorist” Hannah Arendt says in her essay on Benjamin (her cousin by marriage) in ‘Men in Dark Times’:

Hannah Arendt: “It is the element of bad luck, and this factor, very prominent in Benjamin’s life, cannot be ignored here because he himself, who probably never thought or dreamed about posthumous fame, was so extraordinarily aware of it.”

Walter Benjamin: (Theses on the Philosophy of History – Über den Begriff der Geschichte)

“’Among the most noteworthy characteristics of human beings,’ says Lotze, ‘belongs… next to so much self-seeking in individuals, the general absence of envy of each present in relation to the future.’ This reflection shows us that the picture of happiness which we harbor is steeped through and through in the time which the course of our own existence has conferred on us. The happiness which could awaken envy in us exists only in the air we have breathed, with people we could have spoken with, with women who might have been able to give themselves to us. The conception of happiness, in other words, resonates irremediably with that of resurrection [Erloesung: transfiguration, redemption]. It is just the same with the conception of the past, which makes history into its affair. The past carries a secret index with it, by which it is referred to its resurrection. Are we not touched by the same breath of air which was among that which came before? is there not an echo of those who have been silenced in the voices to which we lend our ears today? have not the women, who we court, sisters who they do not recognize anymore? If so, then there is a secret protocol [Verabredung: also appointment] between the generations of the past and that of our own. For we have been expected upon this earth. For it has been given us to know, just like every generation before us, a weak messianic power, on which the past has a claim. This claim is not to be settled lightly. The historical materialist knows why.” Thesis II

Nevertheless his unique career as writer and critic has continued to develop. By 1921, as well a publishing the ‘Critique of Violence’ (‘Zur Kritik der Gewalt’), “Benjamin announces a new project: the launch of a journal to be named after the drawing by Paul Klee (which Benjamin had bought in the spring of that year), the “Angelus Novus” – a drawing Benjamin will keep with him through his remaining years in Germany and subsequent exile. Benjamin’s stated aim in this journal is to “restore criticism to its former strength” by recognizing its foremost task, namely, to “account for the truth of works,” a task he considers “just as essential for literature as for philosophy.” (David S. Ferris)

1923 he began his experimental book entitled One-Way Street, dedicated to Asja L?cis on its publication in 1928:

Walter Benjamin: “But stable conditions need by no means be pleasant conditions, and even before the war there were strata for whom stabilized conditions amounted to stabilized wretchedness.” (One Way Street – A Tour of German Inflation).

“The city furnishes the sensuous, imagistic material for One-Way Street, whilst the genres of the leaflet, placard and advertisement provide the constructive principle by which it is rearranged as a constellation. This formal methodology resembles the technological media of photography and film, as well as the avant-garde practices of Russian Constructivism and French Surrealism. This entails what Adorno describes as a “philosophy directed against philosophy” or what Howard Caygill calls a “philosophizing beyond philosophy”.

The presentation of contemporary capitalism as metropolitan modernity in One-Way Street also marks the turning point in Benjamin’s writings, away from what he retrospectively called “an archaic form of philosophizing naively caught up in nature” towards the development of “a political view of the past”. The theory of experience outlined in his early writings is enlisted for revolutionary ends.” (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

1923 also saw his friend Scholem’s departure for Palestine. “Other than two brief encounters in Paris in the 1930s, the authors were never to meet again. Following Scholem’s departure, the discussion takes the form of letters—those best preserved date from the years 1933 to 1940—that Scholem published with great satisfaction toward the end of his life.” (Eric Jacobson)

Working with Franz Hessel (1880–1941) he translated the first volumes of À la Recherche du Temps Perdu (In Search of Lost Time) by Marcel Proust in 1925. The next year, 1926, he began writing for the German newspapers Frankfurter Zeitung (The Frankfurt Times) and Die Literarische Welt (The Literary World); that paid enough for him to reside in Paris for some months.

July 1926: Benjamin is informed of his father’s death. In December 1926 until the beginning of February 1927 he visits L?cis in Moscow an event that as well as undermining Benjamin’s faith in the relationship also produced his Moscow Diary:

David S. Ferris: “His stay in Moscow leads him to reflect on the choice prompted by his new political leanings: joining the Communist Party or maintaining his independence as a “left-wing outsider” (Moscow Diary, 72). Benjamin decides “to avoid the extremes of ‘materialism” giving the excuse, “as long as I continue to travel, joining the party is obviously something fairly inconceivable” (Moscow Diary, 73). Benjamin will remain a traveler through the different intellectual and political forces he explored in these years. “

Walter Benjamin:

“Only purely external considerations hold me back from joining the German Communist Party. This would seem to be the right moment now, one which it would be perhaps dangerous for me to let pass. For precisely because membership in the Party may very well only be an episode for me, it is not advisable to put it off any longer. But there are and there remain external considerations which force me to ask myself if I couldn’t, through intensive work, concretely and economically consolidate a position as a left-wing outsider which would continue to grant me the possibility of producing extensively in what has so far been my sphere of work. (Moscow Diary)

He continues to reflect in the Diary:

January 9. Further considerations: join the Party? Clear advantages: a solid position, a mandate, even if only by implication. Organized, guaranteed contact with other people. On the other hand: to be a Communist in a state where the proletariat rules means completely giving up your private independence. You leave the responsibility for organizing your own life up to the Party, as it were. But where the proletariat is oppressed, it means rallying to the oppressed class with all the consequences this might sooner or later entail. The seductiveness of the role of outsider – were it not for the existence of colleagues whose actions demonstrate to you at every occasion how dubious this position is. Within the Party: the enormous advantage of being able to project your own thoughts into something like a preestablished field of force. The admissibility of remaining outside the Party is in the final analysis determined by the question of whether or not one can adopt a marginal position to one’s own tangible objective advantage without thereby going over to the side of the bourgeoisie or adversely affecting one’s own work. Whether or not a concrete justification can be given for my future work, especially the scholarly work with its formal and metaphysical basis. What is “revolutionary” about its form, if indeed there is anything revolutionary about it. Whether or not my illegal incognito among bourgeois authors makes any sense. And whether, for the sake of my work, I should avoid certain extremes of “materialism” or seek to work out my disagreements with them within the Party. At issue are all the mental reservations inherent in the specialized work which I have undertaken so far. And the battle will only be resolved – at least experimentally – by joining the Party, should my work be unable to follow the rhythm of my convictions or organize my existence on this narrow base. As long as I continue to travel, joining the Party is obviously something fairly inconceivable.” (Moscow Diary)

Early in 1928, Benjamin and Theodor Adorno meet again in Berlin (having originally met in Frankfurt as students in 1923) and begin a friendship that will last until Benjamin’s death. Through Adorno, Benjamin will deepen his relationship with the Frankfurt School (Institut für Sozialforschung):

“…the School consisted of dissidents who felt at home neither in the existent capitalist, fascist, nor communist systems that had formed at the time. Many of these theorists believed that traditional theory could not adequately explain the turbulent and unexpected development of capitalist societies in the twentieth century. Critical of both capitalism and Soviet socialism, their writings pointed to the possibility of an alternative path to social development.” (Wikipedia)

The School will support Benjamin through some of the most difficult years in the 30s. A complex relationship nonetheless, “even though its two founders, Adorno and Max Horkheimer, both felt that Benjamin was one of the few who were closest to its critical approach”, Benjamin’s path will be more individualist, despite the support of the Frankfurt School and “will develop a more idiosyncratic Marxism that incorporates elements of Brecht and the Frankfurt School along with a messianic sense of history.” (David S. Ferris)

Walter Benjamin: (Theses on the Philosophy of History – Über den Begriff der Geschichte)

“‘Secure at first food and clothing, and the kingdom of God will come to you of itself.” – Hegel, 1807

The class struggle, which always remains in view for a historian schooled in Marx, is a struggle for the rough and material things, without which there is nothing fine and spiritual. Nevertheless these latter are present in the class struggle as something other than mere booty, which falls to the victor. They are present as confidence, as courage, as humor, as cunning, as steadfastness in this struggle, and they reach far back into the mists of time. They will, ever and anon, call every victory which has ever been won by the rulers into question. Just as flowers turn their heads towards the sun, so too does that which has been turn, by virtue of a secret kind of heliotropism, towards the sun which is dawning in the sky of history. To this most inconspicuous of all transformations the historical materialist must pay heed.” – Thesis IV

In May 1929 Benjamin is introduced to Bertolt Brecht by L?cis, the third of these three friendships that were to last until his death, as well as, in Brecht’s case, profoundly shape his commitment to a ‘philosophy of praxis’.

Hannah Arendt: “And there is indeed no question but that his friendship with Brecht—unique in that here the greatest living German poet met the most important critic of the time, a fact both were fully aware of—was the second and incomparably more important stroke of good fortune in Benjamin’s life. It promptly had the most adverse consequences; it antagonized the few friends he had, it endangered his relation to the Institute of Social Research, toward whose “suggestions” he had every reason “to be docile” (Briefe II, 683), and the only reason it did not cost him his friendship with Scholem was Scholem’s abiding loyalty and admirable generosity in all matters concerning his friend. Both Adorno and Scholem blamed Brecht’s “disastrous influence” (Scholem) for Benjamin’s clearly undialectic usage of Marxian categories and his determined break with all metaphysics; and the trouble was that Benjamin, usually quite inclined to compromises albeit mostly unnecessary ones, knew and maintained that his friendship with Brecht constituted an absolute limit not only to docility but even to diplomacy, for “my agreeing with Brecht’s production is one of the most important and most strategic points in my entire position” (Briefe II, 594)”

David S. Ferris: “Scholem recalls the influence of Brecht as the arrival of “a new element, an elemental force in the truest sense of the word in [Benjamin’s] life” (Friendship, 159). Although Benjamin had already experienced an important exposure to Marxism through Asja L?cis and his reading of Lukács, it was not until he formed his friendship with Brecht that this exposure was transformed into a deeper commitment. This transformation resulted from extended conversations in Germany and in Denmark where Benjamin visited Brecht in the summers of 1934, 1936, and 1938.”

It is the influence of these three friends and colleagues that, arguably, provide the key to some of the complexities of probably one of the most difficult of 20th century thinkers:

“Debate over Benjamin’s conception of history was for many years preoccupied with the question of whether it is essentially ‘theological’ or ‘materialist’ in character (or how it could possibly be both at once), occasioned by the conjunction of Benjamin’s self-identification with historical materialism and his continued use of explicitly messianic motifs (Wolhfarth 1978; Tiedemann 1983–4). This was in large part the polemical legacy of the competing influence of three friendships—with Gershom Scholem, Theodor W. Adorno and Bertolt Brecht—applied to the interpretation of Benjamin’s final text, the fragments ‘On the Concept of History’ (‘Über den Begriff der Geschichte’, popularly known as the ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’). Scholem promoted a theological interpretation, Brecht inspired a materialist one, while Adorno attempted to forge some form of compatibility between the two. Yet the question is badly posed if it is framed within received concepts of ‘theology’ and ‘materialism’ (the paradox becomes self-sustaining), since it was Benjamin’s aim radically to rethink the meaning of these ideas, on the basis of a new philosophy of historical time.” (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

In an environment now of world-wide economic crisis (in Germany unemployment had reached 4 million during 1930 itself) Benjamin spent the early 30s working on plans for a left-wing periodical to be entitled ‘Crisis and Critique’, with Ernst Bloch and Brecht, among others. The stimulus came from discussions between Benjamin and Brecht after they had drawn closer in May 1929. “Although not a single issue of the journal was ever published, the project deserves attention as a development in aesthetic politics typical of the years immediately before the Nazi dictatorship….”(Wizla)

The collapse of the Journal did not deter Benjamin from his work. In a 1930 letter to Scholem he wrote: “The goal is that I be considered the foremost critic of German literature.“

Hannah Arendt: “It was no accident that Benjamin chose the French language for expressing this ambition: “Le but que je m’avais proposé…c’est dètre considéré comme le premier critique de la littérature allemande. La difficulté c’est que, depuis plus de cinquante ans, la critique littéraire en Allemagne n’est plus considérée comme un genre sérieux. Se faire une situation dans la critique, cela…veut dire: la recréer comme genre.” (“The goal I set for myself…is to be regarded as the foremost critic of German literature. The trouble is that for more than fifty years literary criticism in Germany has not been considered a serious genre. To create a place in criticism for oneself means to re-create it as a genre”) (Briefe II, 505).”

However, all was to change.

Supported by the big bankers and industrialists who believed he would be “good for business” as well curb the power of the trade unions and the communists, on January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler is named chancellor, turning Germany into a one party state intent on exterminating any and all opposition to its Nazi ideology.

Following the Reichstag Fire in February and witnessing the subsequent persecution of the Jews, in March 1933, Benjamin follows Adorno, Brecht and many other Jewish friends, departing Nazi Germany for the last time, into an exile he divided between Paris, Ibiza, San Remo and Brecht’s house near Svendborg, Denmark. In Ibiza “…he learns that his brother Georg, who has been an active member of the German Communist Party since the late 1920s, has been arrested.” Rejecting the option to emigrate to Palestine, as Scholem suggests, Benjamin returns to Paris in October.

Walter Benjamin: (The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction)

“Fascism attempts to organize the newly created proletarian masses without affecting the property structure which the masses strive to eliminate. Fascism sees its salvation in giving these masses not their right, but instead a chance to express themselves. The masses have a right to change property relations; Fascism seeks to give them an expression while preserving property. The logical result of Fascism is the introduction of aesthetics into political life. The violation of the masses, whom Fascism, with its Führer cult, forces to their knees, has its counterpart in the violation of an apparatus which is pressed into the production of ritual values.”

From 1933 to 1940 he continued to work and travel unraveling the threads of a life that would appeared unfinished as it was in progress but which subsequently others would piece together into the recently acclaimed ‘Walter Benjamin’: a creation no less ‘conceptual’ (and ‘manufactured’) than probably any of the other key concepts he wrote about in an effort to undermine and subvert contemporary culture.

In the summer of 1933 until the autumn, he visits Brecht in Denmark and later visits Italy, where he stays with Dora, his former wife. He stays here throughout 1934 until 35 – a situation he describes as nesting “in the ruins of my own past”. “While he complains of the intellectual isolation of San Remo, these months allow him to work on his notes for the Arcades Project. He also sees his son Stefan again after a gap of almost two years. Stefan, now sixteen years old, had stayed on in school in Berlin and then in Vienna after Dora’s move to Italy.” (David S Ferris). The Passagenwerk or Arcades Project (exploring the Paris of the iron-and-glass covered “arcades”) was begun around 1927 and still uncompleted at the time of Benjamin’s death.

Walter Benjamin: (Theses on the Philosophy of History – Über den Begriff der Geschichte)

“The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the “emergency situation” in which we live is the rule. We must arrive at a concept of history which corresponds to this. Then it will become clear that the task before us is the introduction of a real state of emergency; and our position in the struggle against Fascism will thereby improve. Not the least reason that the latter has a chance is that its opponents, in the name of progress, greet it as a historical norm. – The astonishment that the things we are experiencing in the 20th century are “still” possible is by no means philosophical. It is not the beginning of knowledge, unless it would be the knowledge that the conception of history on which it rests is untenable.” – Thesis VIII

The anti-Semitic Nuremberg Laws (Nürnberger Gesetze) were introduced on 15 September 1935 by the Reichstag; the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour, which forbade marriages and extramarital intercourse between Jews and Germans and the employment of German females under 45 in Jewish households, and the Reich Citizenship Law, which declared that only those of German or related blood were eligible to be Reich citizens; the remainder were classed as state subjects, without citizenship rights. On 14 November, the Reich Citizenship Law officially came into force on that date. Benjamin, along with many other exiles and refugees, was now a man without a country.

Also by 1935 the Institute for Social Research had moved to New York. However in this period they publish 2 essays by Benjamin ‘Problems in the Sociology of Language’, the second ‘Eduard Fuchs, Collector and Historian‘ and shortly after, in 1936: The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit):

“It was produced, Benjamin wrote, in the effort to describe a theory of art that would be “useful for the formulation of revolutionary demands in the politics of art.” He argued that, in the absence of any traditional, ritualistic value, art in the age of mechanical reproduction would inherently be based on the practice of politics.” (Wikipedia)

Walter Benjamin: (The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction)

” “Fiat ars – pereat mundus”, says Fascism, and, as Marinetti admits, expects war to supply the artistic gratification of a sense perception that has been changed by technology. This is evidently the consummation of “l’art pour l’art.” Mankind, which in Homer’s time was an object of contemplation for the Olympian gods, now is one for itself. Its self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order. This is the situation of politics which Fascism is rendering aesthetic. Communism responds by politicizing art.”

“For Benjamin, art, in the form of film—the “unfolding result of all the forms of perception, the tempos and rhythms, which lie preformed in today’s machines”—thus harboured the possibility of becoming a kind of rehearsal of the revolution. “[A]ll problems of contemporary art”, Benjamin insisted, “find their definitive formulation only in the context of film” In this respect, it was the combination of the communist pedagogy and constructive devices of Brecht’s epic theatre that marked it out for him as a theatre for the age of film.” (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

Despite being a refugee Benjamin continues to write, in 1937 he is working on ‘The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire‘ (eventually rejected for publication by the Institute of Social Research in 1938):

Walter Benjamin: “Sundering truth from falsehood is the goal of the materialist method, not its point of departure. In other words, its point of departure is the object riddled with error, with doxa. The distinctions that form the basis of the materialist method, which is discriminative from the outset, are distinctions within this extremely heterogeneous object; it would be impossible to present this object as too heterogeneous or too uncritical. If the materialist method claimed to approach the matter [die Sache] “in truth,” it would do nothing but greatly reduce its chances of success. These chances, however, are considerably augmented if the materialist method increasingly abandons such a claim, thus preparing for the insight that “the matter in itself” is not “in truth.””

…and continuing his interactions with both Adorno, the Frankfurt School and Brecht in exile in Denmark as well as his correspondence with his friend Scholem. This was to continue until the production of Über den Begriff der Geschichte (later published as Theses on the Philosophy of History) written early in 1940 and his last work (with the exception, possibly, of the mysterious manuscript that disappeared in Portbou as Lisa Fittko, in her memoir years later, narrates). As the Nazis close in he spends time in a prison camp near Nevers, in central Burgundy, entrusts many of his manuscripts to Georges Bataille (1897–1962) at the Bibliothèque Nationale, (“Bataille hid the manuscript in a closed archive at the library where it was eventually discovered after the war”) and pays a last visit to Brecht in the summer of 1938.

“In October, Benjamin writes: “I do not know how long it will continue to be physically possible to breathe European air; after the events of the past weeks, it is spiritually impossible even now...” (David Ferris) Benjamin is referring to Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler in the Munich Agreement of September 1938.

Esther Leslie: “But there were other traitors and acts of betrayal to account for, such as the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, signed on 23 August 1939. It contained a secret clause: Poland and eastern areas were to be divided between Germany and the Soviet Union. The Soviets hoped to gain Bessarabia, Latvia, Estonia, Finland and Poland east of the Vistula and San rivers…Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939. The Soviets invaded eastern Poland on 29 September. Non-aggression went alongside a trade treaty and arrangements for extensive exchange of raw materials and armaments. This vile alliance of the vile stemmed from the Communist Party’s attempt at double-dealing. In this instance, the political worldlings are the European proletarians and the betrayers are the politicians who affirmed a supposed anti-fascist tactic. This tactic resulted in the Communist Party welcoming Hitler as Stalin’s ally. The Communist Party leadership called for capitulation before the Nazis. Prior to this accord, Stalin had agreed to withdraw International Brigades from Spain and had reduced aid to the Republican government. The fascist General Franco finally defeated the young democratic government in March 1939.”

The German armies invade Poland in September 1939, and Benjamin along with other German and Austrian nationals is interned at the Olympic stadium in Paris.

Walter Benjamin: (Theses on the Philosophy of History – Über den Begriff der Geschichte)

“The conformism which has dwelt within social democracy from the very beginning rests not merely on its political tactics, but also on its economic conceptions. It is a fundamental cause of the later collapse. There is nothing which has corrupted the German working-class so much as the opinion that they were swimming with the tide. Technical developments counted to them as the course of the stream, which they thought they were swimming in. From this, it was only a step to the illusion that the factory-labor set forth by the path of technological progress represented a political achievement….The Gotha Program [dating from the 1875 Gotha Congress] already bore traces of this confusion. It defined labor as “the source of all wealth and all culture.” Suspecting the worst, Marx responded that the human being, who owned no other property aside from his labor-power, “must be the slave of other human beings, who… have made themselves into property-owners.” – from Thesis XI

Without his German citizenship and now a stateless person, Benjamin applies for French citizenship…He begins to work on his Theses on the Concept of History:

“The theses are notable for Benjamin’s willingness to combine historical materialism and dialectical thought with theological ideas, notably the messianic. This work, not published until after his death, is regarded by Benjamin as not only a summation of the different strands of thought present in his work but an explosive one.” (David Ferris)

Esther Leslie: “How to understand the connection between progress and catastrophe is the task of ‘U?ber den Begriff der Geschichte’. In letters to Max Horkheimer and Gretel Adorno, Benjamin emphasizes the unsystematic character of these historical-philosophical ‘theses’. He claims that his series of graphic and anecdotal vignettes have the ‘character of an experiment’. ‘War and the constellation engendered by it’, Benjamin admits, form the seedbed of the theses. The disjunction of history and theory, the shock of fascism, the horror of militarism, mean that to stop the recurrence of the nightmare new modes of thought must be written and new modes of practice developed. The theses intervene in the present.”

The Theses begin with a story which clearly demonstrate the impoverishment of Marxist and communist policy and practice in the period, where social democracy as well as Stalinism had succeeded finally, after years of struggle, in disempowering the working class.

Walter Benjamin: (Theses on the Philosophy of History – Über den Begriff der Geschichte

“It is well-known that an automaton once existed, which was so constructed that it could counter any move of a chess-player with a counter-move, and thereby assure itself of victory in the match. A puppet in Turkish attire, water-pipe in mouth, sat before the chessboard, which rested on a broad table. Through a system of mirrors, the illusion was created that this table was transparent from all sides. In truth, a hunchbacked dwarf who was a master chess-player sat inside, controlling the hands of the puppet with strings. One can envision a corresponding object to this apparatus in philosophy. The puppet called “historical materialism” is always supposed to win. It can do this with no further ado against any opponent, so long as it employs the services of theology, which as everyone knows is small and ugly and must be kept out of sight.” ) – Thesis I

Esther Leslie: “Benjamin’s friend Scholem later determined many interpretations of the theses, branding them a product of Benjamin’s shocked awakening to the reality of Marxism, at the moment when the Hitler–Stalin pact was signed. And so Scholem fixed an image of Benjamin as a naive, disillusioned utopian. Scholem’s deciphering cancels out Benjamin’s own account of the theses’ motivation in a letter to Gretel Adorno. They represent well-pondered thoughts, for the theses, he divulges, had been germinating for 20 years. That is to say, from 1939 back two decades to 1919 – when, perchance, the seed of the thoughts is planted by the final, fatal struggle of the one political group enthusiastically cited in the theses, Luxemburg’s and Liebknecht’s Spartakus, revolutionary challenger to social democracy, and those two cut down with its tacit approval.”

Walter Benjamin: (Theses on the Philosophy of History – Über den Begriff der Geschichte)

“The chronicler, who recounts events without distinguishing between the great and small, thereby accounts for the truth, that nothing which has ever happened is to be given as lost to history. Indeed, the past would fully befall only a resurrected humanity. Said another way: only for a resurrected humanity would its past, in each of its moments, be citable. Each of its lived moments becomes a citation a l’ordre du jour [order of the day] – whose day is precisely that of the Last Judgment.” – Thesis III

Esther Leslie: “Revolution as interruption in the continuum of history dovetails with Marx’s idea of revolution as the end of the prehistory of humanity and the beginning of true human history. Benjamin’s image is similar to an image of class society in Engels’ Anti-Du?hring (1876–78). This image likewise invokes the image language of locomotion. The bourgeois class, unable to control the energies of the forces of production, is ‘a class, under whose leadership society is racing to ruin like a locomotive whose jammed safety valve the machinist is too weak to open’. Engels’ image suggests the potential barbarism that will arise if the status quo of production relations is not suspended. It poses the question of control of policy and control of the technical apparatus.”

Walter Benjamin: (Theses on the Philosophy of History – Über den Begriff der Geschichte)

“‘We need history, but we need it differently from the spoiled lazy-bones in the garden of knowledge.’

– Nietzsche, On the Use and Abuse of History for Life

The subject of historical cognition is the battling, oppressed class itself. In Marx it steps forwards as the final enslaved and avenging class, which carries out the work of emancipation in the name of generations of downtrodden to its conclusion. This consciousness, which for a short time made itself felt in the “Spartacus” [Spartacist splinter group, the forerunner to the German Communist Party], was objectionable to social democracy from the very beginning. In the course of three decades it succeeded in almost completely erasing the name of Blanqui, whose distant thunder [Erzklang] had made the preceding century tremble. It contented itself with assigning the working-class the role of the savior of future generations. It thereby severed the sinews of its greatest power. Through this schooling the class forgot its hate as much as its spirit of sacrifice. For both nourish themselves on the picture of enslaved forebears, not on the ideal of the emancipated heirs.” – Thesis XII

Esther Leslie: “Benjamin’s theses propagate a politics through images. Their cryptic, poetic references derive a language for thinking when language has failed. Like poems, they are intended to say so much with few words. The politics of images rewrites the terms of historiography, disciplines, thought. To think differently means to recast the available components. What else is Marxism? But Marxism must be something else than what it has become. Quotations from Korsch’s Karl Marx manuscript in the Passagenwerk affirm Marxism, in as much as it provides ‘a completely undogmatic guideline for research and practice’, as understood most clearly, Benjamin suggests, by Sorel and Lenin.”

By early 1940: he is now in active flight from the Nazis, leaving Paris for Lourdes along with his sister Dora on the 13th June, just one day before the Germans entered the city (June 14, 1940). The Vichy government is established in July. Benjamin’s situation becomes more desperate with Jewish refugees being handed over to the Gestapo under the terms of the armistice agreement: “The French government is required to deliver on demand all German nationals designated by the Reich and who are in France, in French possessions, colonies, protectorates and territories under mandate.”

Walter Benjamin: (Letter To Theodor W. Adorno, Lourdes, August 2, 1940)

“The complete uncertainty about what the next day and even the next hour will bring has dominated my existence for many weeks. I am condemned to read every newspaper (they now come out on a single sheet of paper) like a summons that has been served on me and to detect in every radio broadcast the voice of the messenger of bad tidings.”

By August he is informed that the Institute via Max Horkheimer has secured a visa for him to enter the United States. He travels to Marseilles in order to pick up his visa from the American Consulate. “However, he still lacks the necessary exit visa from France. Without this, the other papers are useless. Benjamin stays in Marseilles for over a month in the hope of receiving the exit visa.”

September 1940: he travels from Marseilles to Banyuls-sur-Mer, a small town close to the Spanish border, in the company of Henny Gurland and her son with the intention finally of crossing secretly into Spain and then on to Portugal to secure passage to the United States.

On September 25, as Lisa Fittko’s account narrates, Benjamin, Fittko acting as guide and Gurland and her son explore the clandestine climb along the ‘Route Lister’ over the Pyrenees into Spain. Benjamin, in bad health, sleeps on the path that night fearful that he will not make it back up the following morning. The next morning, on September 26, Fittko returns and the party eventually reaches Portbou on the Spanish side only to find the border closed to those without an exit visa from the French. They are told that they will be returned to France the following morning.

That night, or early the following morning, in the Hotel de Francia in Portbou, Benjamin takes an overdose of the morphine tablets he has kept in his possession since leaving Paris.

“Thus ended the life of the person who would be acclaimed, by George Steiner, for example, as the greatest critic of the twentieth century.” (Michael Tausig)

Walter Benjamin: (Theses on the Philosophy of History – Über den Begriff der Geschichte)

“In relation to the history of organic life on Earth,” notes a recent biologist, “the miserable fifty millennia of homo sapiens represents something like the last two seconds of a twenty-four hour day. The entire history of civilized humanity would, on this scale, take up only one fifth of the last second of the last hour.” The here-and-now, which as the model of messianic time summarizes the entire history of humanity into a monstrous abbreviation, coincides to a hair with the figure, which the history of humanity makes in the universe.” – Thesis XVIII

His death is recorded in the Portbou register as occurring at 10 p.m. on September 26, 1940. Henny Gurland narrates (in a letter to her husband which Scholem later published in his book on Benjamin ‘The Story of a Friendship’) being called to his room early in the morning of the 27th to receive his last instructions before he lapsed into a coma:

“At 7 in the morning Frau Lipmann called me down because Benjamin had asked for me. He told me that he had taken large quantities of morphine at 10 the preceding evening and that I should try to present the matter as illness; he gave me a letter addressed to me and Adorno TH.W… [sic] Then he lost consciousness. I sent for a doctor, who diagnosed a cerebral apoplexy; when I urgently requested that Benjamin be taken to a hospital, i.e., to Figueras, he refused to take any responsibility since Benjamin was already moribund.” (to Arkadi Gurland, October 11, 1940)

In this week, during the course of these 2 eventful days in the life of this radical intellectual, writer and critic of contemporary culture, September 26th and 27th, 1940, in a hotel room in Portbou, Walter Benjamin became another victim of the barbarism that he himself argued was the foundation for all human history to date…..

“There has never been a document of culture, which is not simultaneously one of barbarism.”

He was hastily buried in the catholic graveyard in Portbou as Dr. Benjamin Walter. Within months, Hannah Arendt, herself a refugee passing through, was unable to locate his grave and his bones were possibly placed quite quickly in the common grave (fosa común) there.

Of his short 48 years alive, Walter Benjamin produced an enormous amount of work which is still in the process of being assembled, translated and published. In July this year, 2016, Verso published: ‘The Storyteller: Tales out of Loneliness: “The Storyteller gathers for the first time the fiction of the legendary critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin, best known for his groundbreaking studies of culture and literature.”

So many people have laid claim both ideologically and intellectually to this complex character and the fragmented body of work that he left behind that it might be honest to take ownership of our own use of Benjamin in the ongoing work of developing a culture of liberation, 76 years later, in a different Europe, a more complex world. (Ben Mauk in a recent article says: “Too often, modern academics approach Benjamin as a Rorschach test, gazing at the text and thereby gauging their own predilections toward Marxism, poststructuralism, sociology, Jewish mysticism, urban theory, or modern-day Dadaism. No thinker in modern history is so overdetermined by the pet theories and partial readings of others. And few writers are more diminished in the secondary literature, which invariably suffocates the wit and slyness of the original.”)

Arendt, the non-Marxist critic of the Moscow revolution, might have given the clue, in her essay on Benjamin in “Men in Dark Times.”

Hannah Arendt: “What is so hard to understand about Benjamin is that without being a poet he thought poetically and therefore was bound to regard the metaphor as the greatest gift of language.”

“It seems plausible that Benjamin, whose spiritual existence had been formed and informed by Goethe, a poet and not a philosopher, and whose interest was almost exclusively aroused by poets and novelists, although he had studied philosophy, should have found it easier to communicate with poets than with theoreticians, whether of the dialectical or the metaphysical variety.”

Esther Leslie: “Benjamin’s last jottings look at the nightmare of industrial labour and how so much destruction has become possible amidst such productivity. The next bloody massacre colours these formulations. Benjamin hopes to relate history in ways that do not reinforce the sense that such history as has happened was inevitable. He wants to suggest that the rulers who have ruled need not always rule. It need not go on like this. It must not go on like this, for this is hell. Progress, the continuation of business as usual, is catastrophic”

It is this, almost anarchic and poetic commitment to freedom of thought, of movement, freedom to explore both depth and surface, to move beyond the concept into the more immediate ‘image’, to explore and even transgress the known and accepted boundaries, that arguably brings Benjamin to the forefront of our struggles in this new century to create and develop our own culture of liberation adequate to the present; however this culture will take shape, irrespective, its need is apparent to many of different ideological backgrounds. And however it will manifest:

Benjamin, the Marxist, closes his Theses with the quote:

Walter Benjamin: (Theses on the Philosophy of History – Über den Begriff der Geschichte)

“It is well-known that the Jews were forbidden to look into the future. The Torah and the prayers instructed them, by contrast, in remembrance. This disenchanted those who fell prey to the future, who sought advice from the soothsayers. For that reason the future did not, however, turn into a homogenous and empty time for the Jews. For in it every second was the narrow gate, through which the Messiah could enter.”

There is much to be learnt from the life and work of this writer, ‘poet’, critic, and finally refugee…

Not least, maybe, that all statues, revolutionary or reactionary will fall, but the quest of the human mind to make sense of our being-here, our progress and regress, dialectical or not, our journey to, through and beyond history – this work we have been committed with and burdened to, despite the appalling despair that the evidence of history and our own past give evidence to… goes on.

Scholem writes at the end of ‘Walter Benjamin: the Story of a Friendship’:

“Many years later, in the cemetery that Hannah Arendt had seen, a grave with Benjamin’s name scrawled on the wooden enclosure was being shown to visitors. The photographs before me clearly indicate that this grave, which is completely isolated and utterly separate from the actual burial places, is an invention of the cemetery attendants, who in consideration of the number of inquiries wanted to assure themselves of a tip. Visitors who were there have told me that they had the same impression. Certainly the spot is beautiful, but the grave is apocryphal.”

Taussig, having visited the non-existent grave much later (in the Spring of 2002), adds:

“Benjamin’s life after death was his final essay in this regard. There are no bones we can point to, no honest gravestone, no embalmed corpse, nor locks of hair.”

Bertolt Brecht, on hearing of his friend’s death in 1941, wrote a simple poem:

ON THE SUICIDE OF THE REFUGEE W.B .

I’m told you raised your hand against yourself

Anticipating the butcher.

After eight years in exile, observing the rise of the enemy

Then at last, brought up against an impassable frontier

You passed, they say, a passable one.

Empires collapse. Gang leaders

Are strutting about like statesmen. The peoples

Can no longer be seen under all those armaments.

So the future lies in darkness and the forces of right

Are weak. All this was plain to you

When you destroyed a torturable body.

But Benjamin, surely, deserves the final word:

“The only writer of history with the gift of setting alight the sparks of hope in the past, is the one who is convinced of this: that not even the dead will be safe from the enemy, if he is victorious. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious.”

Theses on the Philosophy of History – Über den Begriff der Geschichte, – Thesis V1

séamas carraher

september 2016

*****

REFERENCES AND SOURCES (Thanks to)

Photograph: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Walter_Benjamin_vers_1928.jpg

Akademie der Künste, Berlin – Walter Benjamin Archiv, this image (or other media file) is in the public domain because its copyright has expired and its author is anonymous.

Biographical Details:

David S. Ferris, The Cambridge Introduction to Walter Benjamin, Cambridge University Press, (2008).

Erdmut Wizisla, Walter Benjamin and Bertolt Brecht – the story of a friendship, Yale University Press, (2004-2009).

Eric Jacobson, Metaphysics of the Profane, Columbia University Press, (2003).

Lisa Fittko, Escape Through the Pyrenees, Northwestern University Press, (1991). Hannah Arendt, Men in Dark Times, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, (1968).

Esther Leslie, Walter Benjamin – Overpowering Conformism, Pluto Press, (2000).

Gershom Scholem, Walter Benjamin: The Story of a Friendship, New York Review Books Classics, (2003).

Michael Taussig, Walter Benjamin’s Grave, The University of Chicago Press, (2006).

The Last Passage, http://walterbenjaminportbou.cat/en/content/el-darrer-passatge

The Storyteller: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/04f63124-69ea-11e6-ae5b a7cc5dd5a28c.html?siteedition=intl)

Ben Mauk, The Name of the Critic: On “Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life” http://theamericanreader.com/the-name-of-the-critic-on-walter-benjamin-a-critical-life/

Walter Benjamin Texts:

Walter Benjamin Bibliography: “The current standard German edition of Benjamin’s work remains Suhrkamp’s seven volume Gesammelte Schriften, edited by Tiedemann and Schweppenhauser, although a new Kritish Gesamtausgabe is currently being edited, also by Suhrkamp and projected at twenty-one volumes over the next decade. The standard English edition is Harvard University Press’ recent four volume Selected Writings, Early Writings, and The Arcades Project.”

Walter Benjamin, SELECTED WRITINGS, VOLUME 1 (1913-1926), Edited by Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings, The Belknap Press Of Harvard University Press (1996).

Walter Benjamin, SELECTED WRITINGS, Volume 4, Michael W. Jennings, General Editor, The Belknap Press Of Harvard University Press (2003).

The Correspondence of Walter Benjamin, 1910-1940, edited and annotated by Gershom Scholem and Theodor W. Adorno, (translated by Manfred R. Jacobson and Evelyn M. Jacobson), University of Chicago Press, (1994).

Walter Benjamin, Rolf Tiedemann, ed., The Arcades Project, New York: Belknap Press, (2002).

READ

Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, (1936)

https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/benjamin.htm

Copy of Frau Gurland’s Letter of October 1, 1941:

Download:

Theses on The Concept of History: http://www.globalrights.info/

Watch:

‘One Way Street – Fragments for Walter Benjamin’, by John Hughes (1993, 58 min,)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-xj7YqPyEOA

Related Articles

What Future, What Human Race, What Meaning: New Zealand’s Animal Welfare Bill?

![]()

This new piece of legislation recognises for the first time “that animals have feelings and can experience pleasure and pain”

Historiador español se adentra en las dudas en torno al posible asesinato de Pablo Neruda

![]()

El también periodista Mario Amorós realizó una rigurosa investigación sobre el último año de vida del poeta, resultado que ahora

The murder of Sakine, Fidan and Leyla: Many Questions to Answer

![]()

On the evening of 9 January 2013 Fidan Dogan (Rojbin), Sakine Cansiz (Sara) and Leyla Saylemez’s friends started to look