August 1969. It all changed forever

![]()

August 69 was a turning point for the North and for many of us who lived here. The Civil Rights Association had been campaigning for an end to discrimination by the Unionist regime at Stormont. I was a member of NICRA and on the committee of its West Belfast branch. I was also very active in the West Belfast Housing Action Committee, campaigning against high rise flats at Divis, and squatting homeless families in the Falls area.

At the start of the year Loyalists and B Specials had attacked a Peoples Democracy March at Burntollet, outside Derry. Sporadic rioting had occurred in the months since then and in Belfast Catholic homes were attacked and some families evicted.

In April Samuel Devenney had been batoned in his home by the RUC. He died three months later on July 16th. That same month an Orange parade had clashed with nationalists in Derry, and in three days of renewed attacks on the Bogside by the RUC, two civilians were shot and wounded. In the course of two days of riots in Dungiven, a Catholic pensioner Francis McCloskey was killed on July 14thin an RUC baton charge. He was first person killed as a result of violence in the most recent phase of conflict.

The British statelet would not concede ‘one man, one vote’, or any principle of equality; it could only be sustained on the basis of inequality. That was what kept Big House unionists in their positions as top dogs; they knew that if change came and inequality was ended they would no longer even have reason to be unionists. The slogans of the regime, ‘Not an inch’ and ‘No surrender’, must prevail at all costs.

On 2 August the Shankill Defence Association, aided and abetted by the RUC and B Specials, launched attacks on Unity Flats after an Orange march. Patrick Corry, a Catholic, was hit by an RUC baton near his home and died four months later. Catholic families were intimidated out of the Crumlin Road area by loyalist gangs.

On 12 August the Orange parade went ahead in Derry. At the edge of the Bogside, young nationalists clashed with loyalists, and the RUC launched baton charges. Fighting side by side with the loyalists, the RUC brought up armoured cars and, for the first time in Ireland, CS gas. For forty-eight hours the mainly teenage defenders of the Bogside used stones, bottles and petrol bombs against the constant baton charges of hundreds of RUC and loyalists. Free Derry was born.

At the height of the Battle of the Bogside I attended an emergency meeting of NICRA in the Wellington Park Hotel in Belfast. It was decided to organize demos throughout the North to stretch the RUC and relieve the pressure on the people of the Bogside. The Belfast demo was to be organized by the West Belfast Housing Action Committee.

In Dublin three cabinet ministers proposed that the Irish army cross the border and seize Derry, Newry and other areas of majority Catholic population. On August 13th An Taoiseach Jack Lynch went on television to announce that ‘the Irish government can no longer stand by and see innocent people injured and perhaps worse’. At around the time of his broadcast I was chairing the protest meeting at Divis Flats. When we marched later to Hasting Street and Springfield Road Barracks we were attacked by the RUC. Later again in the early hours of the morning the RUC opened fire on us from the roof of Springfield Road barracks.

Only half slept I went into work that morning of the 14th, but at 11.30 a.m. someone came into the bar for me, saying, ‘You’re wanted. You should pack in work. The wee man’s looking for you.’ The ‘wee man’ was Billy McMillen.

I went straight from work to Leeson Street, where Billy McMillen and Jimmy Sullivan were in the process of mobilising republicans from all over Belfast and attempting to put in place some defensive arrangements for nationalist areas which were under attack. During the course of that day, there were reports of increasing tension in different parts of the city bordering on loyalist areas, in particular Ardoyne.

That evening a loyalist mob, including many members of the B Specials, armed with rifles, revolvers and sub-machine guns moved from the Shankill Road toward the Falls. They petrol bombed Catholic houses in the streets that lay on their route, beating up their occupants and shooting at fleeing residents. As the mob reached the Falls Road itself, it started to attack St Comgall’s school. A lone IRA volunteer opened fire and the crowd was repelled. The RUC, coming in behind the loyalist civilians and B Specials, opened up with heavy calibre Browning machine-guns from Shorland armoured cars. They directed their firing into the nationalist area, into narrow streets and into Divis Flats itself, where they killed a nine-year-old boy. An RUC sniper from Hasting Street Barracks shot dead a young local man home on leave from the British army.

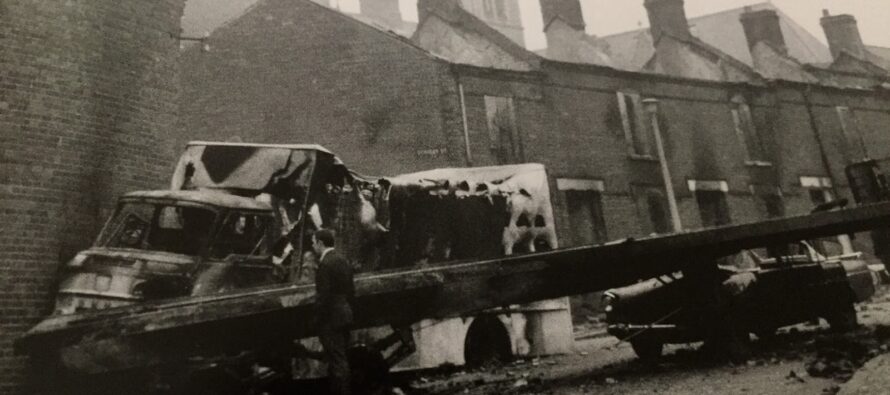

Within a remarkably short space of time, the streets off the Falls Road, and the Falls itself, had been turned into a war zone. Throughout the night, the RUC roared up and down in their armoured vehicles. Dover Street was burned out, and Percy Street, and fighting continued all night in Conway Street. As dawn arose on the morning of 15 August, it did so over a scene of absolute devastation. Six people were dead, five Catholics and one Protestant; about 150 had been wounded by gunfire and 150 Catholic homes had been gutted. The streetscape that I grew up in was gone.

The attacks continued through the 15th. In the Clonard area Gerald McAuley, a fifteen-year-old member of Na Fianna, was shot dead defending Bombay Street, and the street itself was ablaze. Catholic families were fleeing from their homes across Belfast. From the Grosvenor Road, Donegal Road, Tiger’s Bay, York Street, Sandy Row, Highfield and Greencastle: Some fled south, but more moved into safer areas of West Belfast, particularly Andersonstown and Ballymurphy. Relief committees were established in most of these areas.

Local people opened up their homes to these refugees or just emptied their houses of blankets and clothes and gave up their beds to those who had been forced to flee. In the short few weeks of August 1969, all had changed. Forever.

Related Articles

Girls of the Juanambú Battalion

![]()

It was the eighties and President Belisario Betancur opened the negotiating table with the Colombian insurgency.

JOSEBA SARRIONAINDIA, SCRITTORE BASCO

![]()

Joseba Sarrionaindia (1958) scrittore poeta e saggista basco ha vinto il Premio Euskadi della letteratura , che istituisce il Governo della Comunità Autonoma Basca, per il libro “Moroak gara behelaino artean?”. La giuria ha motivato l’assegnazione del premio sottolineando che “era un opera molto solida formalmente, una grande opera, molto documentata, anche nella sua originalità. Passeranno gli anni e l’opera potrà convertirsi in un classico della cultura basca”.

Joseba Sarrionaindia (1958) scrittore poeta e saggista basco ha vinto il Premio Euskadi della letteratura , che istituisce il Governo della Comunità Autonoma Basca, per il libro “Moroak gara behelaino artean?”. La giuria ha motivato l’assegnazione del premio sottolineando che “era un opera molto solida formalmente, una grande opera, molto documentata, anche nella sua originalità. Passeranno gli anni e l’opera potrà convertirsi in un classico della cultura basca”.

Il libro affronta un epoca quella della guerra colonialista spagnola in Marocco negli anni 20 attraverso la descrizione di personaggi e visioni personali sulle culture e il mondo.

Sarrionaindia è considerato un referente della letteratura basca contemporanea. La sua prolifica opera ha attraversato la poetica il romanzo la saggistica passando per una scrittura letteraria sperimentale. Il suo lavoro è stato riconosciuto non solo dai numerosi lettori e lettrici che attendo la sue opere ma anche dalla critica letteraria come il Premio de la Critica di narrativa in euskera, istituito dalla Asociación Española de Críticos Literarios che concesse il premio a Sarrionaindia nel 1986, por Atabala eta euria (Il tamburo e la pioggia), una collezione di racconti e nel 2001 per Lagun izoztua (L’amico congelato), il suo primo romanzo.

Il premio Euskadi che ha una dotazione di 18.000 euro più 4000 euro se l’opera viene tradotta, non verrà dato a Sarrionaindia secondo quanto è stato annunciato dal Governo di Patxi Loepz. La motivazione è data dal fatto che Joseba Sarrioanidia è profuogo dal 1985 quando fuggi dal carcere di Martutene (San Sebtstian) con Inaki Pikaebea ambedue militanti di ETA. Dal 1985 Sarrionaindia scrive dall’ esilio senza che ufficialmente si conosca dove si trovi.

La notizia della concessione dell’ennesimo premio a lo scritto basco ha sollevato il consueto acceso dibattito sui mezzi d’informazione spagnoli. Curiosamente sul quotidiano della destra spagnola, La Razon, ad un articolo dal titolo “Governo basco concede premio a profugo di ETA”, un lettore commenta laconicamente: “Il Premio della Critica di narrativa in euskera è un premio che concede l’Associazione Spagnola dei Critici Letterari nel’l ambito del concorso annuale del Premio della Critica alla migliore opera in prosa scritta in esukera. Nel 1986 venne concesso a Joseba Sarrionaindia per “Atabala eta euria” e nel 2001 lo concessero un’altra volta per “Lagun izoztua”. Non sarà che è un gran scrittore?”

TRADIZIONE E SINCRETISMO di Joseba Sarrionaindia (1984)

Le attuali culture non sono alberi radicati nella terra che tendono i loro rami al vento senza muoversi dal loro luogo. Oggi, come mai nella storia, il mondo è aperto e ci sentiamo parte non solo della nostra terra natale ma di tutto questo mondo, al qualeSakine, Fidan and Leyla: The search for justice continues

![]()

Eight years ago today the bodies of three revolutionary Kurdish women were found at a community centre in a Paris