A changing vision on drugs: Colombia

![]()

From 19 to 21 April 2016 the United Nations host in New York a special session of the General Assembly on drugs (UNGASS). In spite of the obvious fact that many scholars, institutions and civil society from all over the world are changing their points of view on how to lead the fight against drugs, the United Nations, characterized by its slow apparatus and its running-behind-the-facts nature, isn’t expected to adequately get hold of these developments. But the outcome should at least reflect the generalized opinion, based on clear figures published after thorough academic research, that the War on Drugs hopelessly failed.

The agreement on the fourth point of the Agenda, Solution to the problem of Illicit Drugs, made at the peace talks between the Colombian government and the FARC-EP, is an interesting case to show that times might be changing.

In 2000, during the peace process of El Caguán (a peace process that was broken up in 2001), the FARC-EP proposed a Pilot Project for the Substitution of Coca Crops . It was a pilot project for the substitution of illicit crops in a town called Cartagena del Chairá, without using aerial spraying, violence or repression. Although it was positively received by the international community, the government never paid much attention to this proposal and never gave it a try.

However, almost two decades later, at the peace talks in Havana, Cuba, the discussion on illicit drugs was re-taken with the fourth point of the Agenda: Solution to the problem of Illicit Drugs. The insurgency made 50 proposals on the matter, in the same vein as in 2000: No aerial spraying or forced eradication of crops, but a social focus should be the the course to take, at least what the coca growers and the consumers concerns. Thus, it is important to understand that peasants don’t grow coca crops because they want to, but because they don’t have other means of subsistence.

In the agreement, this understanding of the problem of drug-trafficking as a social problem and not a criminal issue is omnipresent. The weakest links of the drug-trafficking chain – that is, the growers and the consumers – are supported with substitution and public health programs, respectively. The substitution programs are closely linked to the first agreement on Comprehensive Rural Reform, as they provide health care, education, technical assistance, soft loans and tertiary roads for peasants to be able to grow legal crops. With the substitution programs the campesinos should be able to change quickly and voluntarily to other crops that should provide them welfare and well-being.

Substitution will be implemented through Comprehensive Plans for Substitution and Alternative Development in each region; these Plans will be build and agreed with representatives from the whole municipality. The community commits to real substitution of crops and to not re-planting them, while the government commits to cease persecution of the communities for two years from the beginning of the implementation.

Prosecution will take place against those who really profit from drug-trafficking: the networks for money laundering and drug-traffickers. Finally, the agreement also recognizes that the problem of illicit drugs isn’t Colombia’s problem; it is an international thing that needs a global solution. Therefore, it was agreed to hold an international conference within the framework of the United Nations, that should open the doors to a new drug policy world-wide.

In February this year, a small delegation including myself visited the guerrilla camps of southern Colombia. I met with a lot of coca growers who had many questions about what had been agreed on the subject of illicit drugs. There was a lot of interest for the subject, because as they put it: this is about our future. There were strong rumours about the government and the FARC-EP who would work together and force the campesinos to eradicate their coca crops, and those who didn’t collaborate would be fumigated. The Peace Delegation had a meeting with social leaders from the area, in which we explained the content, scope and real impact of this agreement.

In March, the government started a project for forced eradication of coca crops in the natural parks of Tinigua and La Macarena, in the South-East of the country, as denounced by the inhabitants of the area.

Forced eradication, without implementing other sustainable substitution programs blatantly violates the spirit of what has been agreed in Havana.

As we are heading towards agreements on a final and bilateral ceasefire and cessation of hostilities, on paramilitarism and on decommissioning of arms – and, in the end, towards a Final Peace Accord, the question is: wouldn’t it be the perfect moment to start implementing some aspects of the agreement on illicit drugs right away?

* member of the Peace Delegation of the FARC-EP in Havana, Cuba

@tanja_FARC

Related Articles

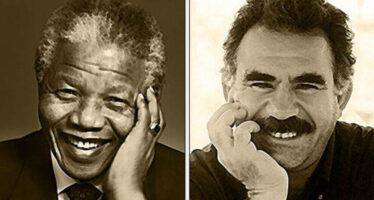

‘International Öcalan Freedom Campaign’ kicks off in South Africa

![]()

South Africa’s largest trade union confederation launched a joint campaign in support of jailed Kurdish people’s leader Abdullah Ocalan.

Women of faith and the Northern Ireland peace process: breaking the silence

![]()

Mairead Maguire, Betty Williams and other members of the “Peace People’ are well-known, but the actions of other groups of Catholic and Protestant women are not

OBAMA NON CHIUDE GUATANAMO

![]()

DemocracyNow. Il presidente statunitense Barack Obama ha firmato un ordine esecutivo che crea un sistema formale per arrestare indefinitivamente i