Resistance and Revolution as Lived Daily Experience: An Interview with Leila Khaled

![]()

by Ziad Abu-Rish

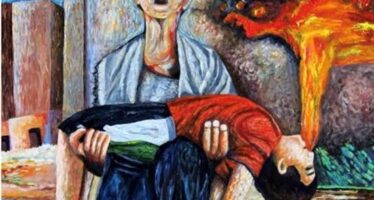

![[Handhalah. Image from manixsblog.blogspot.com] [Handhalah. Image from manixsblog.blogspot.com]](http://www.jadaliyya.com/content_images/3/khalidintro.jpg)

[Handhalah. Image from manixsblog.blogspot.com]

The protests and uprisings that have taken hold across the Arab world have given new contours to processes of politicization, as well as the use of the term “revolution.” Before 2011, references to “the revolution” around the Arab World would conjure images of Gamal Abdul Nasser, Abdul-Karim Qassim, Mu’ammar al-Qaddafi, George Habash, and Yasser Arafat, among others. Put differently, “the revolution”—and all that the term entailed in terms of hopes, dreams, belonging, solidarities, and conflicts—had for many of my generation felt like a distant past, one whose possibilities were foreclosed by a variety of forces; some structural and others contingent. Even those of us that self-identified as leftists, progressives, activists, and/or organizers understood ourselves to be working in a period and context far removed from that described by our parents, mentors, inspirations, and interviewees. As a historian of the second half of the twentieth century, I am often struck by how mobilized the average person was between the 1940s and 1960s, through a combination of political party affiliation, protest participation, and boycott action, to say nothing of simply bearing witness to all that defined those decades. Such degrees of politicization provided a sharp contrast to the effects of post-1970s depoliticization and demobilization across the Arab world as various regimes consolidated their rule and the regional and international order was institutionalized.

The trajectory of Leila Khaled, an icon of the “Palestinian revolution,” one of the tens of thousands that were politicized and mobilized, and an inspiration to many then and since, is one example of the multiplicity of ways in which individuals were politicized and mobilized. Listening to Leila Khaled narrating her experience of such processes was a turning point in my own political trajectory. Day after day of visiting with her, I slowly came to understand that it was not her membership in the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), nor her hijacking of two airplanes (one in 1969 and one in 1970), that made her the person she was. Rather, it was a series of smaller events, processes, and discoveries, which she experienced well before her infamous acts, that politicized and mobilized her. She was neither innately radical nor a conformist.

As 2011 enters its final quarter, Mu’ammar al-Qaddafi has been added to the list of toppled Arab autocrats, while the Ba’thist regime in Syria—which claims the mantle of “resistance” and the legacy of “revolution”—is facing a threat from below the likes of which it has never faced. In Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen, and Libya, “the revolution” is no longer a signifier of a bygone era. It is a lived experience, a reality, and the present. The “revolution” has compelled many to claim and imitate it, in the Middle East and beyond — from Tel Aviv to Madrid and Wisconsin. As one insightful analysis put: “Politics, in short, has returned to the Arab world.” This is true in spite of, and partly as a result of, the varied contradictions of “the revolution” across its different locals, as well as the ongoing struggles to define its scope and legacy.

However, we inhabit a very different world today, defined by different legacies, burdened by revolutions aborted and resistance abandoned. If the previous generation of resistance fighters and revolutionary activists were primarily informed by the experience of colonial rule and its aftermath, today’s generation is primarily informed by decades of indigenous authoritarian rule. Furthermore, those very political parties and ruling regimes that rose to prominence on the rhetoric—and, admittedly, programs—of social revolution and anti-colonial resistance, are now themselves accused of violating principles of social justice and national liberation. While such differences characterize the current processes of politicization and mobilization, the failures and limits of the previous generation’s promises and policies weigh heavily enough to circumscribe said processes with significant degrees of skepticism, cynicism, and fear of the unknown. Nevertheless, a dramatically larger section of the region’s populations are politicized and mobilized than before 2011. A new generation claims “the revolution.”

What follows is a translated transcription of a series of interviews I conducted with Leila Khaled during the summer of 2007. We have much to learn from her and the rest of her generation of activists and revolutionaries. More urgently now, I find myself returning to her experiences, in the context of the Arab uprisings, as we find ourselves confronted by and grappling with the hopes, dreams, demands, and strategies of resistance.

As the question of the “statehood bid”—or rather UN membership—dominates discussions of Palestinian politics, Leila Khaled’s recollection of her experience of the nakba and its aftermath highlight how the deeply rooted questions of destitution, salvation, and return are central to the Question of Palestine. Palestinian refugees throughout the Arab world are six decades after the event still mired in a state of exception. On the one hand, the Israeli government has sought to consolidate its denial of Palestinian return by shifting the goal posts of negotiations from a recognition of “Israel’s right to exist” to one of “Israel as a Jewish state.” On the other, Arab regimes persist in their denial of equal rights for Palestinian refugees residing within their borders, allegedly for the sake of preserving their right of return while at the same time normalizing the condition of their exile. What the statehood discussion completely misses is that the bid itself perpetuates the decades-long Palestinian Liberation Organization’s (PLO) abandonment of Palestinian refugees and Palestinian citizens of Israel.

Occupation is terrorism, to be a refugee is hell.

Having your homeland taken is a crime.

To be a freedom fighter is liberation.

I began with these sentences because I want to focus on a few points in a story about a Palestinian refugee. I was born in Haifa in 1944. However, in 1948 we were driven out by force from our home like all other Palestinians who were evicted from their homeland. We left without my father. We were eight siblings, two brothers and six sisters, including myself. My father was with the resistance fighters at that time and so we had not known where he was since the clashes first broke out in 1947.

My mother decided to take us to her family in Tyre in the south of Lebanon until it was safe for us to return. I was first to be put into the car. I remember all the children crying for the duration of the trip. We did not know where our father was and we were leaving everything behind. My mother asked me why I was crying. I was thinking of my friend Tamara, a girl of my age who was Jewish, a Palestinian Jew. I told my mother that I wanted to be with Tamara. Her mother had opened her home to our family and told my mother that no one could hurt us in her house. She made this gesture immediately after the Deir Yassin massacre. Despite this, the intensification of the clashes and ongoing Zionist operations meant that we had to leave. This is something that has left a deep impression on my psyche until this very day. I remember very clearly the image of people going out into the streets and fleeing. We were going by car while others were walking. We saw them: the elderly, the women, and the children. The weather was not yet hot.

We reached Tyre, and my mother took us to her uncle’s house. The building was surrounded by a big garden with orange trees. The children saw the oranges on the trees and wanted to pick them. My mother slapped us on our hands and said, “These are not your oranges, your oranges are in Palestine.” Sure enough, we had several orange trees on our land in Haifa. I hated oranges for a long time after that. It was not until the 1980s that I began to eat them again. Nevertheless, the sight of oranges takes me back to that day and those words.

My mother refused her uncle’s offer for us all to live in the house with him. Instead, we all lived in the basement, a place that was never meant to be inhabited. All the siblings heard her during the conversation. She was crying the entire time as she repeatedly said that our home was back in Haifa. When asked about the whereabouts of my father, she said she did not know and that he had been working with the revolutionaries. Six months after our arrival in Tyre, our father finally joined us. He had made his way to the Gaza Strip with his fellow fighters. Once in Rafah, he was arrested by the Egyptian authorities and placed in a prison camp. While there, he had suffered a heart attack that left him severely ill. He came to Lebanon with a group of German doctors that had smuggled him out of the camp. He constantly exclaimed: “We lost our country, I lost my family.” The first thing he told my mother when he saw her was that we were not going back. He had realized that our journey would be longer than we all first thought. We did not pay much attention to what he said. Everyday, our siblings would ask our mother about the day of our return.

The first school I attended after arriving in Lebanon was a traditional khuttab school, one where the children would be gathered in the homes of a particular woman who would teach the children how to read the Quran. I changed schools once the Anglican school in Tyre was established in 1950. It was close to our basement home and was basically a giant tent divided into four classes in which students would sit on the ground and listen to a teacher who would teach us from a blackboard propped up by an easel. While there, I approached the headmaster and told him that I knew how to read Arabic. When he asked me to prove it, I read from different chapters of a book. He then wrote a few English letters on the board and asked me to read them. When I was unable to do so, he informed me that I would have to start at the first grade because I did not know English. I was about seven years old at the time. We stayed in that tent and one day during the winter it collapsed over our heads. I went home crying and told my mother that I did not want to go to school. My mother said that I had to and that once I was back in Haifa my school would not collapse on me.

Up to this point in my life, the message was clear. The oranges did not belong to us; ours were in Haifa. The school was not our permanent school; ours was in Haifa. Whenever we asked for new clothes during the holidays, the reply was that our new clothes were to be found in Haifa. All our deprivation was connected to the nakba and all our salvation was connected to our return to Haifa. This was the first thing that was embedded in our conscience: that we must return to Haifa, and that this was our right. For all of us, our future was in Haifa and nowhere else. This was the beginning of the idea of return for our family. Most Palestinian families comprehended their realities in this way. So when children asked about the reason behind their current situation, the answer was that the Zionists had expelled them, occupied their lands, and that there would be a time when we would return to our homes.

The 1940s through the 1960s were decades of intense social and political mobilization throughout the Arab world, ones in which strikes, protests, and marches were regular occurrences. They stand in sharp contrast to the post-1970s era, which was characterized by ever-decreasing mass political party affiliation, protest participation, and boycott action. Such a transformation was a product of intentional policies on the part of regimes—both ‘republican’ and monarchical—that sought to demobilize and depoliticize the general public as the former consolidated their rule. Leila Khaled’s recollection of her activism during her high school and college years is a testament to such a contrast. With very few exceptions, the idea of a general student strike to mark the nakba in the contemporary period would cause many would-be politicized and informed students—to say nothing of teachers, administrators, and parents—to question the efficacy of such an action. High schools and university campuses have become some of the most politically controlled spaces. Nowhere is the success of this strategy more prevalent than in the arguments of the region’s liberal elites, wherein they claim that schools are not the appropriate space for political debates, let alone political action.

In 1958, there was the Lebanese revolt against the term-renewal for President Camille Chamoun. This was a turning point in my life. I was fourteen years old at the time and was very much influenced by my eldest siblings’ involvement in the Arab Nationalist Movement (ANM). Two of my brothers and two of my sisters were members of the ANM. In addition to the consciousness embedded by our parents, the political idea that we had to struggle to go back to our homeland was drawn from my siblings’ political activism.

When the revolt broke out in Tyre in 1958, the army besieged the city and clashes ensued. I took up the role of delivering food to the besieged people by bringing a big tray of food across one of the military checkpoints. When the soldiers questioned me, I would say that I was taking food to my grandmother and thus was able to come and go with some ease. At times, I would be caught in the cross fire and would have to wait until it subsided. Some times, the soldiers would actually help me.

This experience gave me a certain level of respectability, and so I asked to become a member of the ANM. The local ANM leadership said I was too young, that I could be a “friend,” and that after two years pass I would be examined and could become a member. So in 1959 I was accepted as a trainee. That same year, I went to school in Sidon to finish my high school. They required me to repeat the eleventh grade, as they did not want me to graduate from the school having only studied there for one year.

Towards the end of my first year at the new school, I told my fellow students that we needed to strike on 15 May. I was perplexed by their ignorance of the occasion. So I informed them of the anniversary of the Palestinian catastrophe. The school was a boarding school, and so I had to sneak around in the evenings to all the cottages to tell the other students. I coordinated with another student, an ANM member, to mobilize the students to strike. When the morning bell rang on the day of 15 May 1960, and no one responded, we knew that we had succeeded in making the whole school strike. The teachers were calling us to the assembly but we did not respond. The headmaster demanded that we attend. I went and informed her that on this day we were on strike. She asked me where I had learned that word. I told her that the day marks our nakba and that I thought she knew about it. She confirmed that she did but that never in the school’s approximately one-hundred-year history did the students go on strike. I had also sent a message to the boys’ section, some of whom were also members of ANM and other political parties, and who were also conducting a strike.

The administration of the school decided to negotiate with me; that was my first political negotiation. The headmaster wanted all the students to enter the chapel like we did every morning before we started classes to hear a sermon. On this particular day, I gave the talk and focused on the nakba and the reasons for our strike. I told them that this was something normal and part of out lives. The anniversary of the nakba, 15 May, the day of the Balfour Declaration, 2 November, and the anniversary of the UN partition of Palestine, 29 November were the three days every year where all students in Tyre would join with the refugees and protest. This, for me, had been something ordinary and it was unusual to see a school open for classes on one of these days.

At the American University of Beirut (AUB), the ANM was strong among the student body. Elections for the General Union of Palestinian Students (GUPS) were being held during my first year at AUB in 1961. I ran for and was elected to the GUPS administrative committee along with several other people, including As’ad Abdul-Rahman, Bassam Abu-Sharif, Ibrahim al-Abed, and Marwan Baker. It was the first time a woman was elected to that chapter of GUPS.

This one time, we were supposed to organize regular demonstrations in 1963 in solidarity with activities that were ongoing in Nablus at the time. I was distributing pamphlets for the demonstration at night. One of the security guards caught me after curfew and asked me what I was doing. I responded with the fact that I was doing something for my country. He turned out to be a member of the ANM and opened the doors for me and helped me post pamphlets by being a look out. During that time, when AUB students declared demonstrations, the high schools and colleges would follow our lead.

From different parts of the city we gathered at the same point. It was usually the case that the women would be at the front of the demonstration because the assumption was that the police and army would not attack the women. We were a diverse group of Arabs from Bahrain, Kuwait, Lebanon, Palestine, and Saudi Arabia. The army came at us using water hoses and arrested some of us. It was half-past noon and I had to go to a class that started at one. I was drenched and ran back to class, ten kilometers away, getting there just in time. It was exam time for freshman and sophomores. I sat in my seat and received the exam. I turned to the person next to me and told her to let me copy her answers and I just cheated throughout the entire exam.

A few days later, the professor said that the results were in and that there had been a brilliant response. He asked me to stand. He then announced that I had received a grade of zero because I had provided the answers to the sophomore exam and not the freshman exam. I felt ashamed. I told him that I had earned the zero in terms of my answers but that he should appreciate the political work that was accomplished instead. He offered me a make-up exam and I scored very high on it.

Later that week, while in the post office, I received three notes requesting that I report to the Dean’s Office. While there, I was asked if I had read the regulations on the student identification card that prohibited any political activity. I initially denied my political activity, but the Dean confronted me about my pamphlet distribution and placed me on probation. I then told her that I did not accept her warning or her notes because I had been working for my country. I told her that I should be appreciated, as I was not only studying physics and mathematics, but also learning how to love my country. I rejected being reprimanded for working for my country.

Related Articles

Hind Rajab, Almost Six Years Old, Gaza, Palestine: Dead. (A Poem of Barbarism)

![]()

“I’m so scared, please come. Come take me. Please, will you come? Hind Rajab. A Poem of Barbarism, by Séamas Carraher

Reacciones en América Latina a ley aprobada en Israel que legaliza los asentamientos ilegales en Palestina

![]()

son varias las organizaciones internacionales y los Estados que han levantado la voz expresando su repudio y rechazo a dicha iniciativa por parte del Parlamento Israelí

Palestinian Poet calls for All People to Take-Up the Pen (for Gaza)

![]()

Mosab Abu Toha, palestinian poet founder of the Edward Said Library in Gaza, has just issued a call for people to rise up and prove that the pen is and will be – mightier than the sword