Media reform: In the public interest

![]()

Reforming the media after the phone hacking scandal: a Red Pepper roundtable

If powerful interests are to be prevented from closing down the movement for wholesale reform of the media in the wake of the News International phone hacking scandal, there needs to be an equally powerful popular campaign to examine questions of ownership, accountability, ethics and the public interest. This was the theme of exchanges at a Red Pepper roundtable with participants from the Co-ordinating Committee for Media Reform

Michael Calderbank?(Red Pepper)?There’s a danger that the response to phone hacking will be taken really narrowly: ‘why was it allowed to happen, how to clean up this specific practice?’

Dan Hind?(author, The Return of the Public)?That is certainly the line that most of the media will be most comfortable with.

Fiona Swarbrick?(National Union of Journalists)?I think if it is narrowed down in that way then the obvious and easy conclusion will be that this is about a few nasty journalists acting unethically.

DH?It is striking how narrow and constrained the response has been so far, in both print and broadcast.

MC?But clearly that is only the surface. We need to know what were the forces at work structurally that pressured media environments into accepting that normal journalistic standards could be waived.

Dave Boyle?(Co-operatives UK)?Indeed. The context in which journalists are expected to remain faithful to the profit motive, editorial chains of command and a set of ethics will be neatly forgotten. We have to be wary of positing a golden age. There wasn’t a golden age, or if there was it had gone by the 1960s.

DH?There is a temptation to think that everything would be okay if we go back to the good old days of World in Action, the Sunday Times ‘Insight’ team, and so on. The kind of well-intentioned liberal press culture that was stronger in some respects in the 1960s and 1970s didn’t do what was required of it. It couldn’t stop the rise of Murdoch or the new right.

FS?I’m not saying this in a purely ‘good old days’ vein but it was certainly a different scene when the industry was more highly unionised. The NUJ code of conduct held sway, the print unions refused to carry ads for South African Airlines, etc.

DH?The most important difference was that the trade union movement was a major media player through the Daily Herald until the 1960s. Closing the Daily Herald and its rebranding as the Sun is arguably the beginning of the end for the post-war settlement.

Aidan White?(former general secretary, International Federation of Journalists)?The unions were some sort of restraint on the excesses of employers in those days, certainly. Wapping was clearly when it all changed, particularly because it opened the door to levels of corruption that were unheard of before.

FS?That was certainly the point where it broke at News International (NI) and you could extrapolate that to the whole industry. Central to the dispute was the desire to derecognise the unions – not just an economic but a political decision by Murdoch.

MC?What have been the commercial pressures on journalists since then? Presumably many less staff and the remaining staff having less time?

FS?It’s important to understand the culture at NI. When people are both delighted to have a job on a major title and terrified of losing it, and ethics are not prized highly, it is inevitably going to lead to this sort of transgression. It’s rich that the editorial leadership of the paper claims to have no knowledge [of phone hacking]. I don’t know how that sits with a culture of fear. There is not, for example, a problem of bad timekeeping at NI, because people are too scared to do the wrong thing. It seems to me that these same journalists would not chance doing something so risky without sanction from their managers.

Peter Lee-Wright?(Goldsmiths Leverhulme Media Research Centre)?Our researchers found hundreds of journalists all complaining of being tied to desks, required to scrape stories from other sites, not free to leave the office to chase leads. Desk jockeys – but better than being unemployed. It is no coincidence that Nick Davies revealed this in Flat Earth News before going on to break the phone-hacking story. The two are intricately connected.

DH?But the people bribing police and bugging phones weren’t the same as those being pressured to generate more and more churnalism, were they?

FS?No, it wasn’t junior staff in general. But the stakes to be in rather than out of a career only get higher as you get more senior. I’m not excusing it but I think it is certainly about the structure.

PL-W?A dependent staff accepts the local terms of engagement – just like the style bible, or the doxa [French sociologist Pierre] Bourdieu writes about. People find it easier not to question the local modus operandi.

AW?We need to create a working and professional environment where journalists can act freely.

FS?Maybe protection in the form of a conscience clause?

AW?A conscience clause is absolutely essential – or at least formal recognition of the right to act according to some agreed code of practice and ethics.

FS?I have been wondering how a conscience clause could work in practical terms. Maybe as an adjunct to whistleblowing protection?

AW?It should be part of contractual arrangements and allow someone to break with any policy or editorial instruction without fear of victimisation.

DB?I presume newspapers could be regulated to respect such clauses as a condition of continued registration?

AW?We should be looking for a number of policy changes – a conscience clause; new limits on monopolies; a new structure for self-regulation; perhaps a new body to encourage standards and improved training; and also matters related to internal democracy with genuine independence for editors. We need a completely new framework for accountability in the media. Not one framed only in law but the sort of co-regulation that exists in Denmark, where there’s a self-regulating media but the regulatory council can go to law when it needs to enforce its judgements.

PL-W?A 2007 Ofcom survey found 73 per cent of the UK public in favour of media regulation to ensure impartiality, 80 per cent to ensure plurality. But the big circle to square is that regulation is generally nation-bound, while many of the key players are global. Deregulation has accelerated that, and the Press Complaints Commission is only a local distraction in a bigger picture. Even [Sir David] Calcutt, whose 1990 inquiry recommended the establishment of the PCC, disowned it three years later.

AW?I think that a framework of laws that does not encroach upon editorial independence but sets down clear rules that oblige media owners to be transparent about their activities and to respect journalists’ and consumers’ rights is a starting point.

PL-W?Murdoch has given us a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to question the direction of travel. I was astonished how quickly the Murdoch argument – about public service broadcasting not only being inefficient but an unwarrantable brake on free trade – gained traction. Now we can talk about other objectives than profit.

AW?For regulation to work – and I favour forms of self rule on matters of content – it is necessary to prohibit opt-outs by media that don’t want to toe the line. The decision by Express Newspapers to quit the PCC was scandalous because they only did so in order to follow an unethical mode of journalism that had brought them into direct confrontation with their journalists.

MC?Is the PCC dead in the water? What comes next?

DB?Something that can’t be dipped in and out of, so that if the secretary of state rules you into the ambit of the new body, then you’re bound to implement its policies and be bound by its rulings.

AW?The PCC is not dead, but needs to be killed off. Any new structure must be multi-platform. In an age of converged media it is absurd to have different forms of regulation of content when it is the same stream of information being delivered in different ways. What comes next could be a more progressive institution – less focus on policing and more on advocacy for high standards, media education and promoting best practice in journalism. Mediating disputes should be improved by insisting on internal procedures that deal with complaints quickly, fairly and transparently.

DB?I think that’s right. Regulation shouldn’t involve central oversight of operations. Stipulating internal procedures that make the right outcomes more likely seems a better way forward.

PL-W?We need to find a public interest test that ensures plurality without rendering a business worthless. Any new system needs to find a way of marrying the various imperatives, possibly being less concerned about cross-media ownership, allowing expansion where the public interest is met.

AW?We also need to recognise that the media standards and ethics debate feeds into a general concern about corruption and lack of morality in public life. There’s a narrative here that needs to be addressed. How do we create responsible use of information in an open media environment and how do we maintain scrutiny of the centres of power to eliminate the sort of corruption exposed by the phone hacking scandal? These questions are current in all western media systems where market changes and convergence have rendered much of the old structure of media regulation obsolete.

PL-W?The truth is that no one is making money from newspapers. No one has found a way of commodifying their online propositions, outside the specialist sectors. Even Murdoch is struggling. His real business is TV subscriptions and advertising. News is a loss-leader he was all too willing to sacrifice to secure his aborted takeover of BSkyB, and he could close Wapping tomorrow without great loss – he’s already moving to smaller premises. Whatever system evolves has to recognise the interconnectivity of the media business.

FS?Exactly, news is not a big-profit proposition. So we need a model that is not driven by making profit but by producing news.

DH?The more ‘virtuous’ news is, the less profitable (and the less friendly to profit-making) it becomes. You can make money out of celebrity gossip, not so much out of investigations into the financial sector.

AW?This is very important. There needs to be recognition that journalism in the public interest or as a public good will require new forms of funding – levies on advertising, perhaps, or even money from the public purse. We need to recognise that the market will not deliver the information pluralism that democracy needs.

PL-W?There is a model being moderately successfully tried by the Bureau for Investigation in the US that relies for its investigative journalism on trust and foundation funding before finding the appropriate journalistic platform for distribution. Scandinavia and the Netherlands use forms of public support for secondary local newspapers to ensure plurality. But our problem seems to be supporting the primary sources, local or national.

DB?Any new form needs to be from a source that will exist as long as there are people who want news – which means either the state (directly, or through levies) or through people themselves.

MC?But central state direction is not good for pluralism either.

AW?State direction is always to be opposed but looking at community-driven systems that receive state support might be useful. That’s why some form of public support will probably have to be figured into the equation.

DB?My fear with charitable/trust funding is that I’m not sure how much such funding there is for ‘virtuous news’. I think we’d reach peak grant funding fairly quickly.

PL-W?We don’t have the philanthropic resources the US has but it might be a good time to tap these billionaires who have been offering to pay more tax. At least they could see the results!

FS?There isn’t one model for this. It would be good to have different types of owners as well as different owners.

PL-W?The first Leveson ‘seminar’ is on economics, and there is no doubt that addressing these business issues, and accompanying concerns about cross-media ownership, should precede all else. Unless there are realistic options on the table, the corporate lobbyists will have an open field to press the deregulatory case.

DH?Market institutions and public service ones have failed in the last decade, and demonstrably so. Now we’ve exhausted all other options, I think we should try democracy.

PL-W?What people want remains the most problematic part – it is not necessarily what we want to give them. The problem is a compound of

multi-platform explosion, information overload, and consumerist distraction, which has undermined conventional production and distribution models. Some form of responsible stewardship – aggregation in the communal interest – needs to be considered as a way of defraying production costs, just as television supports independent production.

DH?Well, I propose that we take public money and make it available to journalists whose proposals secure a certain threshold of public support. It would establish a direct patronage relationship between the citizen and the journalist and allow people excluded from publicity to mobilise in their own interests. The idea of being able to fund a journalist to investigate wrongdoing at the council, or whatever, is a straightforward proposition for the public.

AW?That’s certainly part of the mix but for it to work there would also have to be other revenue streams from local or state sources.

DB?I was musing with Dan about a matched model, where public funds match those raised or invested locally via a co-op.

MC?It’s important to remember the local aspect, particularly as the local press has been getting hammered. The Mule collective in Manchester (see next page) is one such co-op already established. They could bid for public funds under your scheme?

DH?Outfits like that would benefit from direct public support of the kind I propose. Any publication that actually connected with its audience would.

PL-W?No one will like this but I suspect the long-term structural answer is in to some degree decoupling production and distribution, as imposed on the BBC and ITV. The 500-channel TV set and the internet have destroyed the unitary organ model but what could come out of this are newspapers as production houses of talent, from which digital distribution allows people to source their favourite bits, whether they be football coverage, arts reviews or political comment, and revenues revert to producers. I agree that some form of state-organised/sponsored quality/plurality threshold should ideally be factored in to offset lowest common denominator drift, but there will never be any way of forcing people back to reading the way we did.

AW?The important point is that people should have access to reporting that is not available today. You can’t find public interest journalism of the kind we are talking about even in the middle of the night when the shopping channels hold sway. The point is to encourage this form of journalism and then make it available.

DB?It seems to me that the media organisations that exist and thrive in the world we’re trying to envisage will be the better for being structured around accountability, public interest and – as recipients of public funds – have controls on what they do with generated surpluses. Co-operatives would fit well here.

DH?First, describe the failure of the media and reach a mass audience with that description. Second, propose a clear alternative that is an actual alternative. That’s how the left wins this debate.

PL-W?The challenge is to seize the agenda, excite and involve the public in demanding more from this process, so that the Leveson inquiry cannot allow the government to kick real reform into the long grass. It is a matter of tapping public anger and making real connections with other stories sidelined by commercial fiat to alert the public to possible alternatives – whatever they may be.

MC?We need to be convincing at the level of detail but not leave everyone cold. The raw lobbying power of the corporates will take a lot of resisting. It’s a positive starting point that the Co-ordinating Committee for Media Reform is coming together (see box), linking experts with campaigners.

FS?Yes, the heat needs to stay on from the public or we will have severe difficulties.

AW?Sure, but we need to recognise that the field is open. The public are part of the game now in a way that they never were in the past. The left has an opportunity to take the initiative in an area of public policy where our voices have been largely ignored.

Tip of a larger problem

Dr Aeron Davis, one of the initiators of the Co-ordinating Committee for Media Reform (CCMR), explains the background to its formation

The phone-hacking scandal is the visible tip of a problem with much deeper causes. It is a consequence of larger trends. We need to look at the larger causes not just of phone hacking but many other problematic practices that have become standard in the past two decades.

Many academics and campaign groups have been concerned that the commercial pressures on newsrooms to deliver audiences and cut news-gathering corners have placed impossible pressures on journalists in their day-to-day activities. Phone-hacking is one consequence. There are many others:?computer hacking, unattributed use of PR and newswire material, wholesale plagiarism from other news sources, over-hyped and inflated stories, planting stories and fabricated quotes. Many of us have first-hand accounts and/or experiences of such practices and journalists put under extreme pressures to deliver.

A large part of the problem is an equation of the ‘public interest’ with what the market delivers: what sells most is what is assumed to be in the public’s interest. The need to offer something that grabs the eye, by whatever means, supersedes all else.

But the same public, who are drawn to celebrities and scandals, also want to know about real political issues and how they affect them. In today’s complex, fast-moving society, the public, and indeed many ‘experts’, are unable to keep on top of what is happening in all areas and what is in their interest.

So news needs to be better at looking at things such banking and stock markets, energy issues, inner-city areas and deprivation, and many other subjects that are clearly of public concern but are only reported when there is a financial crisis or widespread rioting. These things are in the public interest but the public may not be aware of them beforehand and may not choose their news on such a basis.

The ownership and regulation question is key. Certain questions of ownership and basic regulation are not complex – if there is the political will, for example, to put limits on media ownership. But regulating private companies operating in a market, and on a range of content and practice issues, is more complex. It is also clear that the economics of the market model of news has been breaking down and is now in crisis – in the UK and elswhere. It is unsustainable – either leading to many news organisation collapsing or the alteration of news in such a way that it no longer resembles ‘news’.

News media are a key public interest concern in democracies, just like the judiciary or police service or education. If left to the market alone, and to some barely-enforced form of self-regulation, as with the banking system or MPs’ expenses, it will be corrupted and break away from its fundamental raison d’etre.

If the first step is recognition of the wider problems, the next is to look at and have an open debate about the many alternatives beyond the raw market. These include combinations of national and local, private and public regulation, funding and infrastructures.

Part of the CCMR’s remit will be to look beyond the UK and also to look at other professions. But first it is necessary to move away from the free market/freedom of the press mantra that is used to fend off all change. These two are not inextricably intertwined and there are many alternatives.

Co-ordinating Committee for Media Reform

In the light of the Leveson inquiry into the regulation and ethics of the press and the review to advise on a new communications bill, there is a real need to co-ordinate the work of advocacy groups campaigning to protect the public interest. The aim of the Co-ordinating Committee for Media Reform (CCMR) is to bring key organisations together.

The CCMR was initiated by reseachers at the Goldsmiths Leverhulme Media Research Centre and has been welcomed by many of the leading media reform groups, including the Campaign for Press and Broadcasting Freedom, Voice of the Listener and Viewer, Media Standards Trust, National Union of Journalists, 38 Degrees, Avaaz, Compass, Coalition of Resistance, Media Wise and others.

For more details see www.mediareform.org.uk

Related Articles

Sakine, Fidan and Leyla

![]()

Sakine CANSIZ (Sara):12 February 1958- 9 January 2013 She was born in Dersim, She was Kurdish and Alevi. She defended

“Aquí es completamente imposible juzgar los crímenes del fascismo español”

![]()

Entrevista a María José Barreiro López de Gamarra y Agustín García Clavé sobre la querella contra el franquismo y la

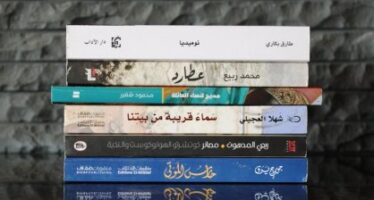

‘Experimental Works’ Chosen for 2016 International Prize for Arabic Fiction Shortlist

![]()

The region’s recent historical tragedies are certainly explored here, from the Palestinian nakba