ON A DAY THIS WEEK in April, 1915

![]()

“Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians.”

Adolf Hitler, (22 August, 1939)

On a day this week, April 24, 1915, the arrest of Armenian intellectuals began in the Ottoman capital of Constantinople that was to be the signal for the mass murder of an estimated 1.5 million Armenians in the almost-unbelievable destruction of a people, that Turkey, through the Committee of Union and Progress (Ottoman Turkey’s governing political party at that time), the perpetrator, to this day still denies ever occurred….

24 April is now the official date of remembrance for the Armenian Genocide. The first commemoration, organized by a group of Armenian genocide survivors, was held in Istanbul in 1919. Following this initial commemoration, the date became the annual day of remembrance for the Armenian Genocide.

“This thing I’m telling you about,

I saw with my own eyes.

Behind my window of hell

I clenched my teeth

and watched with my pitiless eyes:

the town of Bardez turned

into a heap of ashes.

Corpses piled high as trees.

From the waters, from the springs,

from the streams and the road,

the stubborn murmur of your blood

still revenges my ear.”

Words written by the murdered Armenian poet Siamanto, (Adom Yarjanian) one of the intellectuals deported on what became known as Red Sunday, 24 April 1915. Adom Yarjanian was arrested and – along with what was eventually 2,345 other Armenian intellectuals – was moved to two holding centers near Ankara. Few of those arrested survived.

Genocide? What does it mean? Corpses piled high as trees? Water the colour of blood? The crimes men do to men? Here, certainly, it was to become the death march of the ‘infidel’ – from every province of the collapsing empire, ultimately to the deserts of Deir-al-Zour, (what became known as “the epicenter of death”), now in northern Syria, or some other ‘killing centre’. The word has a particular significance to distinguish its meaning from some of its relatives. It is not just an allegation (Turkey, take note). Not even a mere or so-called atrocity, not just another crime against humanity. Not merely a massacre. Less vague maybe than a ‘final solution’. Also much much more than ethnic cleansing. Though we know only too well all of these played their part… Genocide. Even in the presence of denial (now defined as the last stage of genocide; Turkey, take note again): denial…

Raphael Lemkin Defines Genocide

The word was defined by Raphael Lemkin (who lost most of his own family in the Nazi genocide) in his work “Axis Rule in Occupied Europe” (1943). He came up with the term by combining “genos” (race, people) and “cide” (to kill). His definition:

“Generally speaking, genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation. It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be the disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups.”

This was ultimately to become The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, 1948.

In 1915, 2 million Armenians lived in the Ottoman Empire. Today’s Armenian population in Turkey is estimated to be around 60,000 and live dispersed mainly in three major cities, primarily Istanbul.

1915 was also not the first time for the unspeakable to be perpetrated.

Already in the 1890s Sultan Abdul Hamid II had ordered pogroms against the Ottoman’s largest Christian minority that took the lives of an estimated three hundred thousand Armenians. Now, following the arrest and murder of the Armenian intellectuals (“In the end thousands of Armenian cultural leaders were killed, and the core of Armenia’s intellectual life was destroyed.” Peter Balakian says in The Burning Tigris) the entire Armenian population of a disintegrating Ottoman empire were forced to leave their homes and marched into captivity, brutality, starvation and slaughter as well as being forced to endure an endless litany of abuse, torture, robbery, rape, murder, and thirst until death released an estimated 1.5 million Armenians from this unspeakable atrocity at the hands of their fellow humans…

Grigoris Balakian one of the few survivors of the initial roundup in Constantinople and who recorded his experiences of the genocide in his book “Armenian Golgotha“, at one point on his forced march into exile asked the Turkish Captain of constabulary Shukri Bey Shukri:

“Did you shoot them dead or bayonet them to death?” I asked.

“It’s wartime, and bullets are expensive. So people grabbed whatever they could from their villages—axes, hatchets, scythes, sickles, clubs, hoes, pickaxes, shovels—and they did the killing accordingly.”

Haig Baronian (another Armenian survivor, born in 1908 in Baybourt, Turkey – died November 24, 2003, in USA)

“I do not remember how many days our decimated caravan marched. Day by day, the male contingent of the caravan got smaller and smaller. Under the pretext of not killing them if they would hand over liras, gold coins, men would be milked of what little money they had, and then they would be killed anyway. Days wore on. Those who could not keep up were put out of their misery.

Always bodies were found strewn by the wayside. At one place, my little grandmother loudly cursed the Turkish government for its inhumanity. Pointing to us children, she asked: “What is the fault of children to be subjected to such suffering?” It was too much for a gendarme to bear; he pulled his dagger and plunged it into my grandmother’s back. The more he plunged his dagger, the more my beloved Nana asked for heaven’s curses on him and his kind.

Unable to silence her with repeated dagger thrusts, the gendarme mercifully pumped some bullets into her and ended her life. First my uncle, now my grandmother were left un-mourned and unburied by the wayside. We moved on.”

Taner Akçam in his Preface to ‘The Young Turks’ Crime Against Humanity’ records Abdullahad Nuri, the Turkish official in charge of the Armenian resettlement in Aleppo – in a telegram he sent on the 10 January 1916 to the central government:

“Enquiries having been made, it is understood that hardly 10 percent of the Armenians subjected to the general deportations have reached the places destined for them; the rest have died from natural causes, such as hunger and sickness. We inform you that we are working to bring about the same result with regard to those who are still alive, by using severe measures.”

The almost unbelievable inventory of cruelty is almost endless. Few words would do justice even to its memory, let alone comprehend the depths of its inhumanity which seemed to have no end at that time…or later.

Instead: on this day, 24th April, 2018, a poem; though Adom Yarjanian did not survive, his words remain to haunt us all with his terrifying memories…

The Dance (By Siamanto)

In the town of Bardez where Armenians

were still dying,

a German woman, trying not to cry

told me the horror she witnessed:

“This thing I’m telling you about,

I saw with my own eyes.

Behind my window of hell

I clenched my teeth

and watched with my pitiless eyes:

the town of Bardez turned

into a heap of ashes.

Corpses piled high as trees.

From the waters, from the springs,

from the streams and the road,

the stubborn murmur of your blood

still revenges my ear.

Don’t be afraid. I must tell you what I saw,

so people will understand

the crimes men do to men.

For two days, by the road to the graveyard . . .

Let the hearts of the whole world understand.

It was Sunday morning,

the first useless Sunday dawning on the corpses.

From dusk to dawn in my room,

with a stabbed woman,

my tears wetting her death.

Suddenly I heard from afar

a dark crowd standing in a vineyard

lashing twenty brides

and singing dirty songs.

Leaving the half-dead girl on the straw mattress,

I went to the balcony on my window

and the crowd seemed to thicken like a clump of trees.

An animal of a man shouted, “you must dance,

dance when our drum beats.”

With fury whips cracked

on the flesh of these women.

Hand in hand the brides began their circle dance.

Now, I envied my wounded neighbor

because with a calm snore

she cursed the universe

and gave her soul up to the stars . . .

In vain I shook my fists at the crowd.

‘Dance,’ they raved,

‘dance till you die, infidel beauties.

With your flapping tits, dance!

Smile for us.

You’re abandoned now, you’re naked slaves,

so dance like a bunch of fuckin’ sluts.

We’re hot for you all.’

Twenty graceful brides collapsed.

‘Get up,’ the crowd roared,

brandishing their swords.

Then someone brought a jug of kerosene.

Human justice, I spit in your face.

The brides were anointed.

‘Dance,’ they thundered –

here’s a fragrance you can’t get in Arabia.’

With a torch, they set

the naked brides on fire.

And the charred bodies rolled

and tumbled to their deaths . . .

I slammed the shutters

of my windows,

and went over to the dead girl

and asked: ‘How can I dig out my eyes?”

(Translation by Peter Balakian, Grigoris Balakian’s grandnephew)

Unlike Grigoris Balakian, the resourceful priest who survived (and lived until 1934) Atom Yarjanian, poet, writer, also a member of the Armenian National Assembly, and known by his pen name Siamanto was murdered in detention in Ankara in August 1915. Killed by the Ottoman authorities. “Siamanto, the heroic voice of the Armenian people in exile, was detained until August, when he was executed.”

He was born in 1878, in a town on the shores of the river Euphrates. He studied in Constantinople (Istanbul) in 1891 at the Berberian institute, graduating in 1896, the year of the Hamidian massacres. Like many other Armenian intellectuals, he fled the country under threat of persecution. Abdul Hamid’s massacres had made a deep impression on him. He lived in Paris, Vienna, Zurich and Lausanne until the new constitution was proclaimed in Turkey, when he returned to Constantinople, producing his first book of poetry in 1902 under the pen name of Siamanto. In Geneva, Switzerland, he had contributed to the newspaper Droshak, the organ of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, where he also published his poetry. The paper was highly critical of the Ottoman government and demanded equal rights for Armenians and more autonomy. “Siamanto joined the cause and truly believed in an Armenia free of Turkish oppression”.

1909, the Turkish government soon made it clear that Armenians were still not safe by perpetrating the Adana massacre. In response he wrote his famous ‘Bloody News from my Friend’ depicting the atrocities committed by the Ottoman Turkish government against its Armenian population. Twelve poems confronting murder and atrocity, pain, destruction, sadism, and torture, not knowing that a similar fate was to be handed to him soon:

“Don’t be afraid. I must tell you what I saw, so people will understand /the crimes men do to men. For two days, by the road to the graveyard…”

He was 37 years old when he was murdered.

Turkey’s Denial

In a 2015 article Anadolu Agency (the state-run news agency of the Turkish government) responding to Pope Francis’ use of the ‘forbidden word’ on the anniversary of the genocide replied:

“The Ottoman Empire relocated Armenians in eastern Anatolia following the revolts and there were Armenian casualties during the relocation process.”

Yes. 1.5 million “relocated casualties”. Corpses piled high as trees? Water the colour of blood? The crimes men do to men? Genocide…

In 2006, the well-known Armenian-Turkish journalist Hrant Dink was prosecuted under the infamous Article 301 for insulting the Turkish nation. He received a six-month suspended sentence. He was subsequently assassinated by Ogün Samast, a 17-year-old Turkish nationalist.

Taner Akçam, the Turkish historian who won a ruling from the European Court of Human Rights in October 2011 “making it possible to use the term genocide without legal consequences”, writes in ‘The Young Turks’ Crime Against Humanity’:

“Well into the new millennium, Turkish citizens who demanded an honest historical accounting were still being treated as national security risks, branded as traitors to the homeland or dupes of hostile foreign powers, and targeted with threats. In February 2009, during a raid against the ultranationalist terror organization Ergenekon, the personnel of which were believed to be deeply embedded in the military and state bureaucracy, the police seized a list of “Traitors to National Security.” Included on this “hit list” were Hrant Dink, the Istanbul Armenian journalist who was assassinated in 2007…”

Likewise when the Pope used the word “genocide” in his speech marking the 100th anniversary of the Genocide, the Turkish ambassador was recalled from the Vatican. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan complained: “Whenever politicians, religious functionaries assume the duties of historians, then delirium comes out, not fact. Hereby, I want to repeat our call to establish a joint commission of historians and stress we are ready to open our archives. I want to warn the pope to not repeat this mistake and condemn him.”

Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu also criticised Pope Francis’ comments at the time and in particular where he said “the first genocide of the 20th century” had struck Armenians, saying: “We are ready to talk about historical incidents but we will allow nobody to insult or blackmail our nation over historical disputes.”

“Historical disputes”? Yes. 1.5 million “historical disputes.” Corpses piled high as trees? Water the colour of blood? The crimes men do to men? Genocide…

Peter Balakian (in ‘The Burning Tigris’):

“Unfortunately, writing a history of the Armenian Genocide still entails addressing the Turkish government’s continued denial of the facts and the moral dimensions of this history. As Richard Falk, the eminent professor of international law at Princeton University, has put it: The Turkish campaign of denying the Armenian Genocide is “sinister,” singular in the annals of history, and “a major, proactive, deliberate government effort to use every possible instrument of persuasion at its disposal to keep the truth about the Armenian Genocide from general acknowledgment, especially by elites in the United States and Western Europe.”

He goes on: “Today Turkey would like the media and the public to believe there are “two sides” to the Armenian Genocide. When scholars and writers of Armenian descent write about the Armenian Genocide, the Turkish government calls this a biased “Armenian point of view.” This accusation is as slanderous as it would be for the German government to claim that the work of Jewish scholars and writers represented merely a “Jewish side” of the Holocaust, which is to say a biased and illegitimate version of history.”

Likewise genocide scholars have pointed out that removing the Armenian tragedy as well as other ‘mass violence’ from public discourse, creates “a prevailing mind-set that makes future mass crimes possible”:

“With the disappearance of the Armenian Genocide and other mass violence from public discourse,” (he writes) “a prevailing mind-set that makes future mass crimes possible has also been granted tacit support. Today, Turkish society is confronting the source of all its democracy and human rights issues…. Everything—institutions, mentalities, belief systems, creeds, culture, and even communication—is open to question. The time has come—in fact, it is passing—for the social sciences to contribute to the development of democracy and civic culture in Turkey.” (Taner Akçam)

This has to hold a particular relevance when we look at Turkey’s relationship to another ‘subversive’ minority: the Kurds. The Turkish military solution to the ‘Kurdish Question’ in south eastern Turkey (northern Kurdistan) from 2015 to date raises serious questions about what Turkey perceives as a solution to society’s problems. Likewise since the Afrin invasion in January 2018 Kurds have both feared and called out against what they perceive to be the ethnic cleansing of Kurds from northern Syria as well as frequently using the word genocide (Article 3 of the 1948 Convention also prohibits the “Attempt to commit genocide”) for some of the killing committed in both those operations.

Turkey, of course, does not see things this way.

“The Armenian Allegation of Genocide” – Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Foreign Affairs

“For during these waning days of the Ottoman Empire did millions die, Muslim, Jew, and Christian alike…

…Yet Armenians have attempted to extricate and isolate their history from the complex circumstances in which their ancestors were embroiled. In so doing, they describe a world populated only by white-hatted heroes and black-hatted villains. The heroes are always Christian and the villains are always Muslim. Infusing history with myth, Armenian Americans vilify the Republic of Turkey, Turkish Americans, and ethnic Turks worldwide. Armenians bent on this prosecution choose their evidence carefully, omitting all evidence that tends to exonerate those whom they presume guilty, ignoring important events and verifiable accounts, and sometimes relying on dubious or prejudiced sources and even falsified documents. Though this portrayal is necessarily one-sided and steeped in bias, the Armenian community presents it as a complete history and unassailable fact.”

Peter Balakian:

“The Association of Genocide Scholars and the community of Holocaust scholars—which is to say, the professional scholars who study genocide—affirm that the extermination of the Armenians was genocide, and that this genocide took the lives of about two-thirds of the Armenian population of Ottoman Turkey. Genocide scholars are comfortable putting the number of dead at more than a million (some estimates put it at 1.5 million). Out of exasperation with Turkish denial, the Association of Genocide Scholars in 1997 passed unanimously a resolution stating the facts of the Armenian Genocide. In June 2000, 126 leading Holocaust scholars, also deeply troubled by Turkey’s campaign of denial, published a statement in the New York Times: “126 Holocaust Scholars Affirm the Incontestable Fact of the Armenian Genocide and Urge Western Democracies to Officially Recognize It” .

The Kurds show the way forward?

In Diyarbakir (Amed), northern Kurdistan, as the centenary of the Armenian Genocide approached, Fréderike Geerdink for Public Radio International (PRI) looked at how the Kurds, unlike most of their Turkish neighbours, have faced up to 1915. There are no Armenians any longer in Amed, at least in public (“There are only the so-called “hidden Armenians”: the descendants of those who converted to Islam to save their lives, or of Armenian children who were saved from the massacres by Ottoman soldiers and Kurds and were brought up as Muslims.”)

Geerdink interviewed Abdullah Demirbaş, a Kurdish politician, who admitted that the Kurd’s own struggle since the 1980s “has helped them come to terms with their role in the Armenian genocide”.

‘“Part of this vision is apologizing for our part in the genocide. The Kurds may have been used by the state […] but they should have resisted. Our silence makes us guilty.”

Demirbas has backed up his words with action. During his time as mayor of Diyarbakir’s old town, the municipality began disseminating information in Kurdish and Armenian, where before there was only Turkish. The Surp Giragos Armenian church was also restored and is to be the center point of this year’s commemorations.”’

You would wonder then if the Kurdish project of Democratic Confederalism could offer a solution to some of the causes of mass murder? Demirbaş is quoted as saying:

“If we call these lands ‘Kurdistan’ as a land where only Kurds live, or ‘Armenia’ as a land where only Armenians live, what difference would there be between us and the Turkish state? We have to create a ground for living together on these lands, which belong to all of us. We should no longer rely on the nation-state concept, which created these massacres in the first place.”

Whether the experiment currently being implemented in Rojava, northern Syria by the Kurds and the other minority peoples there offers a solution to humankind’s dilemmas into the future, we are still left with this past and the need “to bury our dead for fear that they walk to the grave in labour” (Dylan Thomas). Maybe, in the end, what we are left with, facing beyond the silence that the unspeakable produces, are some serious questions about what makes us, as a species, the way we are?

Theodor Adorno wrote in Prisms, 1967, (in “An Essay on Cultural Criticism and Society,” Prisms, p.34):

“The more total society becomes, the greater the reification of the mind and the more paradoxical its effort to escape reification on its own. Even the most extreme consciousness of doom threatens to degenerate into idle chatter. Cultural criticism finds itself faced with the final stage of the dialectic of culture and barbarism. To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. And this corrodes even the knowledge of why it has become impossible to write poetry today. Absolute reification, which presupposed intellectual progress as one of its elements, is now preparing to absorb the mind entirely. Critical intelligence cannot be equal to this challenge as long as it confines itself to self-satisfied contemplation.”

And one aspect of our critical intelligence – the one observing these bodies strewn along the side of the road, corpses piled high as trees, water the colour of blood, and the crimes men do to men – must be to question, up to the present, our own less-than-adequate attempts at ‘humanity’ and whether it is possible to transform what we are right now, that is, whether there will ever be a time in history when this practice of inhumanity, one being against the other, ends?

“Dehumanization, although a concrete historical fact, is not a given destiny but the result of an unjust order that engenders violence in the oppressors, which in turn dehumanizes the oppressed…” Paulo Freire wrote in ‘Pedagogy of the Oppressed’…

William Saroyan (in ‘The Armenian & the Armenian’, the final piece in his second book, ‘Inhale & Exhale’, 1936):

“I should like to see any power of the world destroy this race, this small tribe of unimportant people, whose history is ended, whose wars have all been fought and lost, whose structures have crumbled, whose literature is unread, whose music is unheard, whose prayers are no longer uttered. Go ahead, destroy this race. Let us say that it is again 1915. There is war in the world. Destroy Armenia. See if you can do it. Send them from their homes into the desert. Let them have neither bread nor water. Burn their houses and their churches. See if they will not live again. See if they will not laugh again. See if the race will not live again when two of them meet in a beer parlor, twenty years after, and laugh, and speak in their tongue. Go ahead, see if you can do anything about it. See if you can stop them from mocking the big ideas of the world, you sons of bitches, a couple of Armenians talking in the world, go ahead and try to destroy them.”

Genocide? So what does it mean now? Corpses piled high as trees? Water the colour of blood? The crimes men do to men? After the death march of these 1.5 million ‘infidels’ towards the deserts of Deir-al-Zour, through many many places of death… Genocide?

On this day, this week, this 24 April, we need to say to Turkey:

“It is not just an allegation… Not even a mere or so-called atrocity, not just another crime against humanity. Not merely a massacre. It is now surely less vague than a ‘final solution’. It is much much more than an ethnic cleansing… Not delirium, Mr President. Not just 1.5 million “historical incidents” then and not just 1.5 million “historical disputes”, now, Mr. Prime Minister… Nor, sadly, an insult… not even blackmail, Turkey! Genocide.”

Genocide…

For those of us left to make sense of it now, over 100 years later, for at least one day in the year, it must also be, still, a type of desperation: a desperate cry from the depths of whatever it is within us that has the potential to discover what is human, our individual and collective humanity?

A “type of desperation, a desperate cry from the depths”

…on this day then of all days …another poem by another being who survived another genocide, survived to write and then, one day, near the banks of the River Seine, in Paris, decided to stop surviving…

Deathfugue (by Paul Celan)

Black milk of daybreak we drink it at sundown

we drink it at noon in the morning we drink it at night

we drink and we drink it

we dig a grave in the breezes there one lies unconfined

A man lives in the house he plays with the serpents he writes

he writes when dusk falls to Germany your golden hair Margarete

he writes it and steps out of doors and the stars are flashing he whistles his pack out

he whistles his Jews out in earth has them dig for a grave

he commands us strike up for the dance

Black milk of daybreak we drink you at night

we drink in the morning at noon we drink you at sundown

we drink and we drink you

A man lives in the house he plays with the serpents he writes

he writes when dusk falls to Germany your golden hair Margarete

your ashen hair Shulamith we dig a grave in the breezes there one lies unconfined.

He calls out jab deeper into the earth you lot you others sing now and play

he grabs at the iron in his belt he waves it his eyes are blue

jab deeper you lot with your spades you others play on for the dance

Black milk of daybreak we drink you at night

we drink you at noon in the morning we drink you at sundown

we drink you and we drink you

a man lives in the house your golden hair Margarete

your ashen hair Shulamith he plays with the serpents

He calls out more sweetly play death death is a master from Germany

he calls out more darkly now stroke your strings then as smoke you will rise into air

then a grave you will have in the clouds there one lies unconfined

Black milk of daybreak we drink you at night

we drink you at noon death is a master from Germany

we drink you at sundown and in the morning we drink and we drink you

death is a master from Germany his eyes are blue

he strikes you with leaden bullets his aim is true

a man lives in the house your golden hair Margarete

he sets his pack on to us he grants us a grave in the air

he plays with the serpents and daydreams death is a master from Germany

your golden hair Margarete

your ashen hair Shulamith

(This version translated by Michael Hamburger)

Simple as it may sound, what else is there to say, confronted with this enormous and immeasurable darkness, only: We must live in hope.

Genocide. Hope. Words written “after Auschwitz”. After the Armenian Genocide.

We Are Few But We Are Called Armenians (Paruyr Sevak)

We are few, truly, but we are Armenians

And by being few we do not succumb

Because it is better to be few in life, then to control life by being many

Because it is better rather to be few, then to be masters by being many

Because it is better to be few, then to be swindlers

We are few, yes, but we are Armenians

And we know how to sign from yet unhealed wounds

But with a new juice we rejoice and we cheer

We know how to thrust into the foe’s side

And how to lend a helping hand to our friend

How to repay goodness which was done to us

by compensating for each one by ten

And the benefit of it just in the sun

We vote with our lives, not only with our hands

Yet if they desire to rule us with force

We know how to smoke and how to quench their fire

And if it is needed to disperse darkness

we can turn into ashes like burning candles

And we know as well how to make love with lust

And we do this always by respecting others

See we do not put ourselves above anyone,

but we know ourselves We are called Armenians

And why should we not feel pride about that

We are, We shall be, and become many.

séamas carraher

REFERENCES, SOURCES & Links (thanks to)

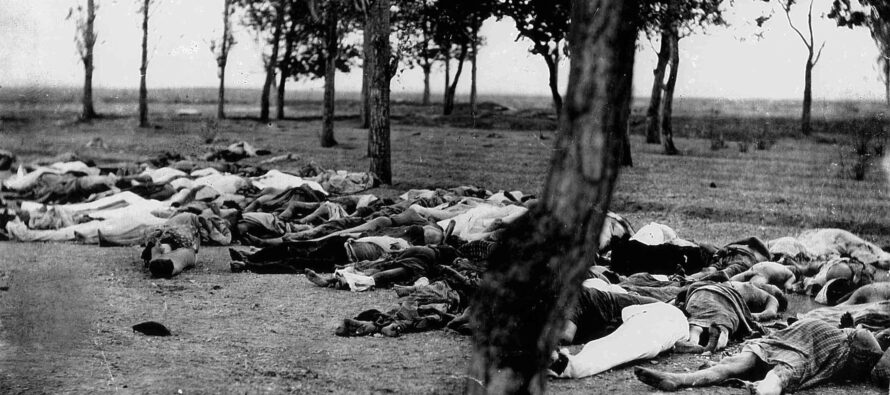

Image:

“Those Who Fell by the Wayside”

By Henry Morgenthau [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Original description: “THOSE WHO FELL BY THE WAYSIDE. Scenes like this were common all over the Armenian provinces, in the spring and summer months of 1915. Death in its several forms—massacre, starvation, exhaustion—destroyed the larger part of the refugees. The Turkish policy was that of extermination under the guise of deportation.”

Image taken from Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story, written by Henry Morgenthau, Sr. and published in 1918.

Hitler Quote:

“Our strength consists in our speed and in our brutality. Genghis Khan led millions of women and children to slaughter – with premeditation and a happy heart. History sees in him solely the founder of a state. It’s a matter of indifference to me what a weak western European civilization will say about me. I have issued the command – and I’ll have anybody who utters but one word of criticism executed by a firing squad – that our war aim does not consist in reaching certain lines, but in the physical destruction of the enemy. Accordingly, I have placed my death-head formation in readiness – for the present only in the East – with orders to them to send to death mercilessly and without compassion, men, women, and children of Polish derivation and language. Only thus shall we gain the living space (Lebensraum) which we need. Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians? (Adolf Hitler)

The text above is the English version of the German document handed to Louis P. Lochner in Berlin. It first appeared in Lochner’s What About Germany? (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1942), pp. 1-4. The Nuremberg Tribunal later identified the document as L-3 or Exhibit USA-28. Two other versions of the same document appear in Appendices II and III. For the German original cf. Akten zur Deutschen Auswartigen Politik 1918-1945, Serie D, Band VII, (Baden-Baden, 1956), pp. 171-172.

See:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hitler%27s_Obersalzberg_Speech

http://armgenocide.blogspot.ie/2008/04/

Paul Celan (Paul Antschel) was born in 1920 into the largely Jewish, German-speaking city of Czernowitz in Romania. He survived the Nazis (and their Romanian allies) ghettos, forced labour and the death camps that killed his parents, eventually ending up in Paris. “Late in his life it is said he was repeatedly hospitalized for severe depression.” He died by drowning in the Seine river in Paris, also on a day this week, April 20, 1970.

Read:

Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

Approved and proposed for signature and ratification or accession by General Assembly resolution 260 A (III) of 9 December 1948, entry into force 12 January 1951, in accordance with article XIII.

Poems of Atom Yarjanian (1878-1915):

https://allpoetry.com/Atom-Yarjanian

Poems on Video:

“The Dance” by Siamanto (Atom Yarjanian) 1910 – read by Anoush Nakkashian

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qeSxEwF75-w

Galway Kinnell Reads “Todesfuge” (Death Fugue) By Paul Celan

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eUVMi1e8wDE

William Saroyan – “I should like to see any power of the world destroy this race”

Video – Music:

Don Seroj – Armenian Genocide

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zNIUm5wZAwk

Deleyaman Duduk and Violin – April 24 Armenian Genocide 4K

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C8jrD6ZHBBo

Isabel Bayrakdarian and The Minasyan Duduk Quartet – Dle Yaman || Music of Armenia

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lAfZZyWUFZQ

“Dle Yaman – English translation and the meaning of the song – “Dle Yaman” was one the thousands of ancient Armenian folksongs collected and preserved by Komitas Vardapet (1869-1935), a composer, musicologist and the founder of modern Armenian classic music. Komitas’s life was spared through the intervention of a group of influential friends during the Armenian Genocide in 1915, but he lived to see everyone he loved to die in the Genocide. Komitas had never recovered from the emotional shock. He died in a psychiatric mental institute. Dle Yaman is a love song, but it acquired a different meaning taking into account the tragic events of 1915-1920 and the destiny of Komitas. Being a love song Dle Yaman is also an anthem of the Armenian Genocide and of Komitas tragic life story.

Our homes face each other, Oh, dle yaman, Isn’t it enough, That my eyes send you a sign? Oh My love! Oh, dle yaman, Isn’t it enough, That my eyes send you a sign? Oh My love! Dle yaman…. the sun has touched the Mount Ararat Oh, dle yaman, Still I remain yearning for my love Oh My love! Oh, dle yaman, Still I remain yearning for my love Oh My love!”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ajl3Y8_zgrk

Video: Genocide

The Armenian Genocide Testimony Collection – 30 Days of Testimony

“The testimony clip series “30 Voices from the Armenian Genocide”, was produced to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide and the first integration of full-length Armenian Genocide testimonies into the Visual History Archive. To help put the testimony clips into perspective, each one is introduced by experts in the field of the Armenian Genocide. The presenters also recommend additional resources for those who would like to learn more. The 30 testimony clips are just a sample of some of the stories from the full-length testimonies viewable in the Visual History Archive.”

https://sfi.usc.edu/collections/armenian

The Armenian Genocide Timeline: Documentaries

The Genocide Education Project

http://www.uacla.com/genocide-timeline.html

Armenian genocide: survivors recall events 100 years on

“The water was the colour of blood”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bAAq1zSXCug

Noam Chomsky 2014 The Armenian Genocide

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V0QBFNUIIBk

Related Articles

“A poet takes care of the silence”

![]()

Italian poet Anna Lombardo meets poet Odveig Klyve. The other interviews to poets Anna Lombardo made for Global Rights can

For The Kurdish People in Diyakabir and Beyond

![]()

Dear President Recep Tayyip Erdo?an, for fuck’s sake, stop killing people in Northern Kurdistan

Silk Road’s revival and challenges

![]()

by Hajrudin Somun* A soldier stands guard in front of the Idkhar Mosque in the Chinese city of Kashgar, a