Trump’s visit marks the start of shock doctrine Brexit

![]()

Trump landed with a negotiating position. If Theresa May’s Brexit plan goes ahead, it would probably “kill the deal”, he told The Sun, referring to the trade agreement he’s here to discuss.

To understand what’s really going on here, we need to rewind by a week, to a tweet from the man who funded Brexit, Arron Banks:

“In Bermuda with @Nigel_Farage saying he will come back as UKIP leader if Brexit not back on track , Tories in marginally seats watch out! Lightening storm hit studio shortly afterwards – omens…” https://t.co/h3EZwGT8nO

— Arron Banks (@Arron_banks) July 9, 2018

Perhaps the most apt of omens we could ask for, the prospect of two of the men who delivered Brexit returning from a tax haven to take their country back. Because whatever “Leave” meant to the millions who voted for it, it has always been about something else for the elite who pushed it – and for Donald Trump more than any of them.

The term “Shock Doctrine” was first used by Naomi Klein in her 2007 book of the same name. With the subheader “The rise of disaster capitalism”, she outlined her thesis: while advocates of neoliberal capitalism said it would dance hand in hand with democracy as these ideologies encircled the world, in fact neoliberalism marches in step with violence and disaster.

In Chile, the dictator Augusto Pinochet delivered the radical right plans concocted by economist Milton Friedman on the back of his 1973 military coup and aided by the torture and murder of thousands, often using electronic batons to literally shock people into acquiescence. Throughout the late 20th century, the International Monetary Fund came into former colonies when they faced crises and used the leverage of much-needed loans to force mass privatisations, tax cuts for the rich and public spending cuts for the rest.

After the tsunami swept across the Indian Ocean in 2004, beaches were privatised by hotels. After Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005, Klein has since written, “I watched hordes of private military contractors descend on the flooded city to find ways to profit from the disaster, even as thousands of the city’s residents, abandoned by their government, were treated like dangerous criminals just for trying to survive.”

From the privatisation of war in Iraq and Afghanistan to the divvying up of oil contracts afterwards, the rich and powerful and their pet governments have become expert in using crises to ensure that they continue to profit as ordinary people lose everything.

Perhaps the most important example of disaster capitalism is what happened as the former Soviet Union fell apart in the 1990s. While President Boris Yeltsin bumbled on the international stage, Russia was plundered. Powerful men took control of key economic assets, moving billions of dollars offshore and turning themselves into oligarchs overnight.

In the midst of all of this, Britain has played an important role. The vestigial empire – Overseas Territories like Bermuda, Gibraltar, and the Cayman and Virgin Islands; and Crown Protectorates the Isle of Man, Jersey and Guernsey – transformed themselves, along with London, into the planet’s most important network of tax havens and secrecy areas. When the world’s oligarchs asset strip countries in crisis and move the plunder offshore, they are usually placing it under the protection of Her Majesty’s Navy.

As Peter Geoghegan and I have followed the dark money that funded the Brexit campaign, there is one consistent factor: almost all of it has been funnelled through these quirks in the British constitution. Whether it’s Northern Ireland with its secrecy laws or Arron Banks’ use of Gibraltar and Mann as shelters for his cash, the people who funded the drive to pull Britain out of the EU certainly know how to navigate the dark corners of the country’s constitutional cave network.

This, surely, is the easiest way to understand the various connections between Brexit and Russia. The Kremlin is no longer the heart of the Soviet Union. It’s at the centre of a network of billionaire power built by Russia’s disaster capitalist-in-chief: Vladimir Putin, sometimes said to be the richest man in the world. It’s no surprise that this vortex of neoliberal plunder would want to use crisis to influence the management of their preferred money laundry.

It’s not just Russians. Britain’s role for many of the world’s richest lies in our skill in cleaning up their questionable money. But the EU is endlessly threatening to regulate, to force more transparency, to make it harder to stash their cash in the world’s laundromat.

And it’s not just about tax havens and their users: look at the fortunes made on the money markets as the price of the pound crashed around on referendum night, or the high-risk corners of the City of London which seemed much more likely to support Brexit than their more conventional banking neighbours. Or look at the mercenaries.

Over the past fifteen years, a key part of disaster capitalism has been the increasing privatisation of the military. “Security firms” have emerged, and taken on work once done by armies and police forces. And again, Britain is at the centre of this: as the NGO War on Want has documented, since the invasion of Iraq, Britain has become the world leader in this mercenary industry. Once again, the links between the Brexit elite and the world of privatised security are everywhere we turn in our investigations: Cambridge Analytica is the wing of privatised defence contractor SCL. Veterans for Britain – one of the campaign groups investigated by the Electoral Commission – has a string of connections to the private security industry.

With every industry comes a lobby, and both the money-laundering lobby and the mercenary lobby have a strong interest in the UK slipping outside the common rules and regulations of the EU. It’s no surprise that they came in behind Brexit.

This week has been bookended by two key moments for these groups. On Monday, Dominic Raab was appointed as Brexit secretary. Perhaps most famous for saying British workers are too lazy, Raab has been nurtured by the Institute for Economic Affairs, the UK’s original radical right think tank, which refuses to say how it’s funded, but which has published more than one ‘report’ on the advantages of tax havens since the Brexit vote. It seems likely he’ll end up essentially as the IEA’s man in government.

The week ends with the arrival of Trump in the country. Protests will largely focus on his racism and misogyny, but it’s important that we also remember the reason that the government tells us he’s here: for talks on a trade deal.

Here we will finally get to the main point of Brexit, for those who led the charge. Last autumn, the IEA published two sides of A4 – tweeted again this week – arguing ‘let’s get ready for no deal Brexit’. “A ‘no deal’ scenario in which the UK simply leaves the Single Market and Customs Union in 2019, does not have to be the ‘catastrophe’ that many fear.” they say in their summary “…the UK would be able to crack on with its own trade deals with the rest of the world”.

Read between the lines, and I’d argue they are saying what Klein would predict: in the crisis of a cliff-edge Brexit, people will be forced to accept the kind of trade deal that groups like the IEA dream about.

Its brief note focuses largely on the most obvious question of any trade deal: tariffs. It will come as a surprise to no one to hear that a free-market think tank is against them. What it doesn’t talk about is what will likely be most of the content of any major trade deal with the US: what’s normally known as ‘non-tariff barriers’. These can include regulations which protect our food, our hedgerows, our hedgehogs, our education system, our air and our water from whatever scheme businesses might concoct to profit from them. They can include many of our basic rights as workers, students, consumers and citizens. The ownership of British healthcare – as my colleague Caroline Molloy has explained – will be up for grabs, as will any other corner of life currently protected from the profiteering of big business.

During the vast fight over the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, we saw how far the Obama administration tried to force the EU to kneel before American capital. We saw how they wanted any disputes to be arbitrated in corporate courts. Many of the worst of those proposals were stopped by the strength of the left across Europe uniting to resist them.

A cliff-edge Brexit would leave the British left standing alone against our own, bespoke, Trumpian redraft of TTIP. We won’t have Belgian parliaments to hold up the process, or German NGOs to interpret the text, or the combined trade power of Europe to stand up to the White House.

Watch their speeches and read their reports, and it’s increasingly clear that this is what Britain’s hard Brexit elite want. The crisis of a no-deal Brexit is the disaster they seek to force through a US trade deal which will turn Britain into a deregulated offshore haven for the rich, and a service economy workhouse for the rest, just as they’ve long proposed.

Adam Ramsay – July 2018

* Adam Ramsay is the Co-Editor of openDemocracyUK and also works with Bright Green. Before, he was a full time campaigner with People & Planet.

Source:

This article was originally published in the independent online magazine openDemocracy

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence. If you have any queries about republishing, please contact info@opendemocracy.net.

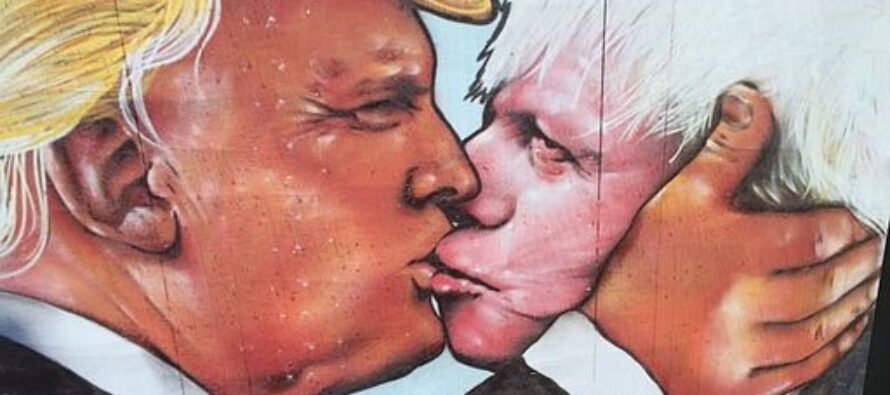

Image:

Donald Trump and Boris Johnson

By Matt Brown from London, England (Donald Trump and Boris Johnson) [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Related Articles

Lehman Brothers collapse, five years on: ‘We had almost no control’

![]()

A Lehman Brothers employee carries her belongings out of its London office on the day the bank collapsed in 2008.

El paro sube en 51.185 personas en agosto

![]()

La creación de empleo retrocede, con 136.834 afiliaciones a la Seguridad Social menos.- La contratación indefinida vuelve a caer ALEJANDRO

Syria: US withdrawal does not erase Coalition’s duty towards Raqqa’s devastated civilians

![]()

UPDATE: This has been modified to reflect a clarification by US forces that the early stages of the withdrawal involve military equipment, but not troops, leaving Syria