ON A DAY THIS WEEK, IN MARCH, 2012. Adrienne Cecile Rich

![]()

In a day this week, the 27th March, 2012, at her home in Santa Cruz, California, the American poet, feminist and social critic Adrienne Cecile Rich died, after over six decades of creative work. In her essay “As if your life depended on it” she wrote:

Adrienne Rich:

“You must write, and read, as if your life depended on it. That is not generally taught in school. At most, as if your livelihood depended on it: the next step, the next job, grant, scholarship, professional advancement, fame; no questions asked as to further meanings. And, let’s face it, the lesson of the schools for a vast number of children—hence, of readers—is This is not for you.

To read as if your life depended on it would mean to let into your reading your beliefs, the swirl of your dreamlife, the physical sensations of your ordinary carnal life; and, simultaneously, to allow what you’re reading to pierce the routines, safe and impermeable, in which ordinary carnal life is tracked, charted, channeled…

To write as if your life depended on it: to write across the chalkboard, putting up there in public words you have dredged, sieved up from dreams, from behind screen memories, out of silence—words you have dreaded and needed in order to know you exist. No, it’s too much; you could be laughed out of school, set upon in the schoolyard, they would wait for you after school, they could expel you. The politics of the schoolyard, the power of the gang.

Or, they could ignore you.

Born on May 16, 1929 in Baltimore, in the U.S. state of Maryland, into a privileged environment (her father Head of Pathology at the prestigious Johns Hopkins Medical School and her mother formerly a musician and composer). Rich grew up immersed in the culture of the classics found in her father’s well stocked library (as well as the work of Auden, MacNeice and Yeats), nurtured by his apparently at times overbearing encouragement of her literary talents, particularly the art of writing poetry. She would later expand her horizons (“…Shelley, in fact, saw powerful institutions, not original sin or “human nature,” as the source of human misery. For him, art bore an integral relationship to the “struggle between Revolution and Oppression...”) and free herself from these patriarchal limits.

From 1947-51 she escaped the pressures of family by entry to Radcliffe College, in Cambridge, Massachusetts (“a female coordinate institution for the all-male Harvard College”). At the close of her education there she received her bachelor’s degree in English and more importantly, in 1951, her first book A Change of World was published after winning both the 1951 Yale Younger Poets Competition, (judged that year by WH Auden) as well as his notoriously patronising Preface to this her first book: “The typical danger for poets in our age is, perhaps, the desire to be ‘original,’ he wrote. ‘Miss Rich, who is, I understand, 21 years old, displays a modesty not so common with that age, which disclaims any extraordinary vision, and a love for her medium, a determination to ensure that whatever she writes shall, at least, not be shoddily made…. [the poems were] neatly and modestly dressed, speak quietly but do not mumble, respect their elders but are not cowed by them.” Soon after she continued her flight from family to Europe from where she returned in 1953, to Massachusetts to marry Alfred Conrad, a Harvard economist she had met as an undergraduate: “I married in part because I knew no better way to disconnect from my first family,” she says. “I wanted what I saw as a full woman’s life, whatever was possible.” She would later put this period of her life – which embraced an America coping with the Korean War (despite peace talks held in July and October, 1951, the Korean War will continue until July 1953) and the changes that the rest of the 50’s would bring – into perspective through her poems and essays, including the righteous anger of indictment where it was due:

Adrienne Rich (‘Poetry and Commitment, An Essay‘, 2007):

“I’m both a poet and one of the “everybodies” of my country. I live, in poetry and daily experience, with manipulated fear, ignorance, cultural confusion, and social antagonism huddling together on the fault line of an empire. In my lifetime I’ve seen the breakdown of rights and citizenship where ordinary “everybodies,” poets or not, have left politics to a political class bent on shoveling the elemental resources, the public commons of the entire world into private control. Where democracy has been left to the raiding of “acknowledged” legislators, the highest bidders. In short, to a criminal element.”

Likewise in poetry:

Adrienne Rich ( from ‘A Wild Patience Has Taken Me This Far, 1978 – 1981’):

For Ethel Rosenberg

convicted, with her husband, of “conspiracy to commit espionage”: killed in the electric chair June 19, 1953

1.

Europe 1953:

throughout my random sleepwalk

the words

scratched on walls, on pavements

painted over railway arches

Liberez les Rosenberg!

Escaping from home I found

home everywhere:

the Jewish question, Communism

marriage itself

a question of loyalty

or punishment

my Jewish father writing me

letters of seventeen pages

finely inscribed harangues

questions of loyalty

and punishment

One week before my wedding

that couple gets the chair

the volts grapple her, don’t

kill her fast enough

Liberez les Rosenberg!

I hadn’t realized

our family arguments were so important

my narrow understanding

of crime of punishment

no language for this torment

mystery of that marriage

always both faces

on every front page in the world

Something so shocking so

unfathomable

it must be pushed aside

2.

She sank however into my soul A weight of sadness

I hardly can register how deep

her memory has sunk that wife and mother

like so many

who seemed to get nothing out of any of it

except her children

that daughter of a family

like so many

needing its female monster

she, actually “wishing to be an artist

wanting out of poverty

possibly also really wanting

revolution

that woman strapped in the chair

no fear and no regrets

charged by posterity

not with selling secrets to the Communists

but with wanting to distinguish

herself being a bad daughter a bad mother

And I walking to my wedding

by the same token a bad daughter a bad sister

my forces focussed

on that hardly revolutionary effort

Her life and death the possible

ranges of disloyalty

so painful so unfathomable

they must be pushed aside

ignored for years

3.

Her mother testifies against her

Her brother testifies against her

After her death

she becomes a natural prey for pornographers

her death itself a scene

her body sizzling half-strapped whipped like a sail

She becomes the extremest victim

described nonetheless as rigid of will

what are her politics by then no one knows

Her figure sinks into my soul

a drowned statue

sealed in lead

For years it has lain there unabsorbed

first as part of that dead couple

on the front pages of the world the week

I gave myself in marriage

then slowly severing drifting apart

a separate death a life unto itself

no longer the Rosenbergs

no longer the chosen scapegoat

the family monster

till I hear how she sang

a prostitute to sleep

in the Women’s House of Detention

Ethel Greenglass Rosenberg would you

have marched to take back the night

collected signatures

for battered women who kill

What would you have to tell us

would you have burst the net

4.

Why do I even want to call her up

to console my pain (she feels no pain at all)

why do I wish to put such questions

to ease myself (she feels no pain at all

she finally burned to death like so many)

why all this exercise of hindsight?

since if I imagine her at all

I have to imagine first

the pain inflicted on her by women

her mother testifies against her

her sister-in-law testifies against her

and how she sees it

not the impersonal forces

not the historical reasons

why they might have hated her strength

If I have held her at arm’s length till now

if I have still believed it was

my loyalty, my punishment at stake

if I dare imagine her surviving

I must be fair to what she must have lived through

I must allow her to be at last

political in her ways not in mine

her urgencies perhaps impervious to mine

defining revolution as she defines it

or, bored to the marrow of her bones

with “politics”

bored with the vast boredom of long pain

small; tiny in fact; in her late sixties

liking her room her private life

living alone perhaps

no one you could interview

maybe filling a notebook herself

with secrets she has never sold

Her second book The Diamond Cutters, appeared in 1955, a book she would later say she would have preferred not to have been published, but the 50’s overall marked a retreat from her creative work and between 1955 and 1959 her three children (David, Pablo and Jacob) were born as well as the experience that would later produce (in 1976): ‘Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution’, combining her experience of motherhood with feminist theory: “Before Of Woman Born, there had been little to no scholarly feminist analysis of the institution of motherhood. The book has since become a classic feminist text, and motherhood has become an essential issue of feminism.” (Linda Napikoski, 2014)

Adrienne Rich: (‘Of Woman Born – Motherhood as Experience and Institution’)

“I wrote it as a concrete and particular person, and in it I used concrete and particular experiences of women, including my own, and also of some men. At the time I began it, in 1972, some four or five years into a new politicization of women, there was virtually nothing being written on motherhood as an issue. There was, however, a movement in ferment, a climate of ideas, which had barely existed five years earlier. It seemed to me that the devaluation of women in other spheres and the pressures on women to validate themselves in maternity deserved exploration. I wanted to examine motherhood—my own included—in a social context, as embedded in a political institution: in feminist terms.”

This creative hiatus was broken in 1963 by the publication of ‘Snapshots of a Daughter in Law‘ a work she received significant criticism for (“I was seen as ‘bitter’ and ‘personal’; and to be personal was to be disqualified, and that was very shaking because I’d really gone out on a limb… I realised I’d gotten slapped over the wrist, and I didn’t attempt that kind of thing again for a long time.“) From this point until her death in 2012 Adrienne Rich would work through each decade alternating (if not synthesizing) the role of poet, intellectual, critic (“political in her ways…”), as well as shaping a voice with which to express her identity as a woman (“The enemy, always just out of sight / snowshoeing the next forest, shrouded / in a snowy blur, abominable snowman / —at once the most destructive / and the most elusive being / gunning down the babies at My Lai / vanishing in the face of confrontation.” (‘The Phenomenology of Anger‘, 1972)

In summarising her voyage through these often tumultuous times, the critic Mary Lynn Broe, describes her as:

“… [Adrienne Rich] one of America’s most significant living writers and a poet and a public intellectual with a substantial audience both inside and outside the academy. … from the passionate and eloquent poems of a largely personal feminist awakening, from the mid 60s to the early 80s, to the equally (if differently) passionate and eloquent poems of a more broadly public re-imagination of our country and its history, beginning with her work of the mid 1980s. Rich has remained committed to the reconstruction of poetry’s place in public as well as private life, nationally and globally.”

Likewise Carol Muske in the New York Times Book Review was to write that Rich began as a “polite copyist of Yeats and Auden, wife and mother. She has progressed in life (and in her poems …) from young widow and disenchanted formalist, to spiritual and rhetorical convalescent, to feminist leader…and doyenne of a newly-defined female literature.”

However, like for so many of that era, it would be the 1960’s and its dreams and hope (and finally despair: “There was a sense coming out of the 60’s that revolution was not going to be accomplished overnight.“) for change that was to shape her work and the position from which she would confront it (“The freedom of the wholly mad / to smear & play with her madness / write with her fingers dipped in it / the length of a room” – ‘The Phenomenology of Anger‘, 1972.) In 1959 her third and last child, Jacob, was born. By the end of 1963 there were 15,000 US military advisers in South Vietnam. On August 28th, 1963, Martin Luther King delivered his “I have a dream” speech. And in the midst of these events Rich’s Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law, was “a much more personal work which explored her female identity, and marking a transformation in both her style and subject matter.” Rich and her family were to move to New York (1966) where she would begin teaching the graduate poetry course at Columbia University. The 1960’s saw radical ideas “flooding the campus, in particular the anti-Vietnam movement and women’s liberation.” In 1968, she also took up a teaching post at City College as part of the Seek programme which attempted to reach out to underprivileged students. “The SEEK program, a remedial English program for poor, black, and third world students entering college, which was raising highly political questions about the collision of cultural codes of expression and the relation of language to power, issues that have consistently been addressed in Rich’s work. She was also strongly impressed during this time by the work of James Baldwin and Simone de Beauvoir. Though Rich and her husband were both involved in movements for social justice, it was to the women’s movement that Rich gave her strongest allegiance. In its investigation of sexual politics, its linkage, as Rich phrased it, of ‘Vietnam and the lovers’ bed,’ she located her grounding for issues of language, sexuality, oppression, and power that infused all the movements for liberation from a male-dominated world.” (Deborah Pope) “In her work, radical ideas would begin to surface in the 1969 collection Leaflets, but more decisively in her prose, which had now begun appearing in feminist journals.” (John O’Mahoney) New York also offered the promise of the New Left, of ‘women’s liberation’, the Civil Rights struggle, the anti-war war movement, Black Panthers… “In 1968, she signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.” This move ‘to the left’ (“her sometimes polemical leftism” David Orr) was to profoundly shape the direction of her life and her struggle with language and the society that gave it its ultimate meaning, i.e.: “The tradition of those who have written against the silences of their time and location.” (‘Poetry & Commitment.’)

It was this dialectic between a world struggling for change and a poet whose voice sought to give a presence to that change – (“No one writes lyrics on a battlefield / On a map stuck with arrows / But I think I can do it if I just lurk / In my tent pretending to / Refeather my arrows” ‘Quarto’, 2009) – that was also to shape her output away from the formally accomplished work that Auden had admired so much to the often-struggling-dense-complex production that was to continue up to her death. In her essays she writes:

Adrienne Rich (“From a notebook, March 7, 1974″):

“The poet today must be twice-born. She must have begun as a poet, she must have understood the suffering of the world as political, and have gone through politics, and on the other side of politics she must be reborn again as a poet.

But today I would rephrase this: it’s not a matter of dying as a poet into politics, or of having to be reborn as a poet “on the other side of politics” (where is that?), but of something else—finding the relationship.”

…the challenge of which it would seem, for those of us on the Left, in this end-of-history post-cold-war, post-communist-state-experiment period, has been demonstrated, if not always clearly articulated?

Rich was also forced to confront the challenge of this process of change within herself. In 1970 she and her husband Alfred Conrad (2 January 1924 – 18 October 1970) separated. Shortly afterwards he shot himself. It was October 1970. Angela Davis was arrested in New York. Salvador Allende was elected president in Chile. Alfred Conrad was 46 years old. In turmoil after the suicide (“It was shattering for me and my children,” she says. “It was a tremendous waste. He was a man of enormous talents and love of life.”) Rich walked away from a world she experienced as having no place for her as a woman, a patriarchal universe that silences and represses so much: “I would have loved to live in a world / of women and men gaily / in collusion with green leaves, stalks, / building mineral cities, transparent domes, / little huts of woven grass / each with its own pattern— / a conspiracy to coexist / with the Crab Nebula, the exploding / universe, the Mind—” (‘The Phenomenology of Anger‘, 1972) “In the years that followed, Rich began to cut ties with old friends, including some of her closest confidants. She left New York for the West Coast, where she would live for the rest of her life. She came out as a lesbian. She began to write more prose, revealing a talent for polemic. Her feminist politics bloomed suddenly into a very explicit sort of radicalism, the kind unafraid to march onto the pages of intellectual journals and complain that ‘the way we live in a patriarchal society is dangerous for humanity.’” (Michelle Dean, 2016)

Adrienne Rich (Writing of Ann Sexton, 1928-1974, in 1974):

“In 1966 I helped organize a read-in against the Vietnam War, at Harvard, and asked her to participate. Famous male poets and novelists were there, reading their diatribes against Mc-Namara, their napalm poems, their ego-poetry. Anne read—in a very quiet, vulnerable voice—”Little Girl, My Stringbean, My Lovely Woman”—setting the first-hand image of a mother’s affirmation of her daughter against the second-hand images of death and violence hurled that evening by men who had never seen a bombed village.”

“By 1970, partly because she had begun, inwardly, to acknowledge her erotic love of women, Ms. Rich and her husband had grown estranged. That autumn, he died of a gunshot wound to the head; the death was ruled a suicide. To the end of her life, Ms. Rich rarely spoke of it.” (Margarita Fox, NYT)

It was also around this time that Rich discovered the writing of Mary Wollstonecraft, James Baldwin, and, particularly, Simone De Beauvoir, whose ‘The Second Sex’, written in 1949 (on “the pervasiveness and intensity and mysteriousness of the history of women’s oppression”) “…talked about things that I had been half thinking but feeling no confirmation for“. A quick glance at the notes and references to her published writing clearly shows someone exploring the boundaries and diversity of human thought, which for Rich was also to include her identity “as a Jewish woman, the Holocaust and the struggles of black women“.

Adrienne Rich: (1972)

Diving into the Wreck (“one of the most beautiful poems to come out of the women’s movement,” Cheryl Walker)

First having read the book of myths,

and loaded the camera,

and checked the edge of the knife-blade,

I put on

the body-armor of black rubber

the absurd flippers

the grave and awkward mask.

I am having to do this

not like Cousteau with his

assiduous team

aboard the sun-flooded schooner

but here alone.

There is a ladder.

The ladder is always there

hanging innocently

close to the side of the schooner.

We know what it is for,

we who have used it.

Otherwise

it’s a piece of maritime floss

some sundry equipment.

I go down.

Rung after rung and still

the oxygen immerses me

the blue light

the clear atoms

of our human air.

I go down.

My flippers cripple me,

I crawl like an insect down the ladder

and there is no one

to tell me when the ocean

will begin.

First the air is blue and then

it is bluer and then green and then

black I am blacking out and yet

my mask is powerful

it pumps my blood with power

the sea is another story

the sea is not a question of power

I have to learn alone

to turn my body without force

in the deep element.

And now: it is easy to forget

what I came for

among so many who have always

lived here

swaying their crenellated fans

between the reefs

and besides

you breathe differently down here.

I came to explore the wreck.

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

I came to see the damage that was done

and the treasures that prevail.

I stroke the beam of my lamp

slowly along the flank

of something more permanent

than fish or weed

the thing I came for:

the wreck and not the story of the wreck

the thing itself and not the myth

the drowned face always staring

toward the sun

the evidence of damage

worn by salt and sway into this threadbare beauty

the ribs of the disaster

curving their assertion

among the tentative haunters.

This is the place.

And I am here, the mermaid whose dark hair

streams black, the merman in his armored body

We circle silently

about the wreck

we dive into the hold.

I am she: I am he

whose drowned face sleeps with open eyes

whose breasts still bear the stress

whose silver, copper, vermeil cargo lies

obscurely inside barrels

half-wedged and left to rot

we are the half-destroyed instruments

that once held to a course

the water-eaten log

the fouled compass

We are, I am, you are

by cowardice or courage

the one who find our way

back to this scene

carrying a knife a camera

a book of myths

in which

our names do not appear.

Erica Jong: (From Ms. 1973)

“This stranger-poet-survivor carries ‘a book of myths’ in which her/his ‘names do not appear.’ These are the old myths … that perpetuate the battle between the sexes. Implicit in Rich’s image of the androgyne is the idea that we must write new myths, create new definitions of humanity which will not glorify this angry chasm but heal it.”

John O Mahoney (The Guardian):

“Diving into the Wreck, published in 1973, was even more forceful and assured, qualities that earned Rich the national book award, shared with Allen Ginsberg. Aside from the title poem, the volume also included “The Phenomenology of Anger”, in which Rich argued that “anger can be visionary, a kind of cleansing clarity“. Viewed as hectoring and hysterical by some male critics, the poem proclaimed: “the only real love I have ever felt/ was for children and other women/ everything else was lust, pity,/ self-hatred, pity, lust.” However, it was in Twenty One Love Poems (1976), that all the strands of Rich’s personal and political transformation came together: “The rules break like a thermometer,/ quicksilver spills across the charted systems/ we’re out in a country that has no language/ …whatever we do together is pure invention/ the maps they gave us were out of date/ by years…”

It is 1974: her collection ‘Diving into the Wreck‘, (“Coming out here we are up against it / Out here I feel more helpless / with you than without you”) a collection of exploratory and often angry poems, (“…of disaster, with a willingness to look into it deeply and steadily, to learn whatever dreadful information it contains, to accept it, to be part of it, not as victim, but as survivor…” Ruth Whitman, Harvard Magazine,1975) shares the 1974 National Book Award for Poetry with Allen Ginsberg and his ‘The Fall of America’. Declining to accept it individually, Rich is joined onstage by the two other feminist poets nominated, Alice Walker and Audre Lorde, to accept the prize on behalf of all women “whose voices have gone and still go unheard in a patriarchal world.” Poetry becomes a political act, like the 1968 Black Power / Human Rights salute at the Olympic Games.

Adrienne Rich (‘Poetry and Commitment, An Essay‘, 2007):

“For now, poetry has the capacity—in its own ways and by its own means—to remind us of something we are forbidden to see. A forgotten future: a still-uncreated site whose moral architecture is founded not on ownership and dispossession, the subjection of women, torture and bribes, outcast and tribe, but on the continuous redefining of freedom—that word now held under house arrest by the rhetoric of the “free” market. This ongoing future, written off over and over, is still within view. All over the world its paths are being rediscovered and reinvented: through collective action, through many kinds of art. Its elementary condition is the recovery and redistribution of the world’s resources that have been extracted from the many by the few.”

In 1976, Rich began her ‘partnership’ with Jamaican-born novelist and editor Michelle Cliff, which lasted until her death. In her controversial work Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution, published the same year, Rich acknowledged that, for her, lesbianism was a political as well as a personal issue, writing, “The suppressed lesbian I had been carrying in me since adolescence began to stretch her limbs.” 1978, the ‘Dream of a Common Language’ (which included the chapbook ‘Twenty-One Love Poems’, “marked the first direct treatment of lesbian desire and sexuality in her writing, themes which run throughout her work afterwards, especially in A Wild Patience Has Taken Me This Far (1981) and some of her late poems in The Fact of a Doorframe (2001).”

Adrienne Rich (Twenty-One Love Poems,)

I

Wherever in this city, screens flicker

with pornography, with science-fiction vampires,

victimized hirelings bending to the lash,

we also have to walk . . . if simply as we walk

through the rainsoaked garbage, the tabloid cruelties

of our own neighborhoods.

We need to grasp our lives inseparable

from those rancid dreams, that blurt of metal, those disgraces,

and the red begonia perilously flashing

from a tenement sill six stories high,

or the long-legged young girls playing ball

in the junior highschool playground.

No one has imagined us. We want to live like trees,

sycamores blazing through the sulfuric air,

dappled with scars, still exuberantly budding,

our animal passion rooted in the city.

II

I wake up in your bed. I know I have been dreaming.

Much earlier, the alarm broke us from each other,

you’ve been at your desk for hours. I know what I dreamed:

our friend the poet comes into my room

where I’ve been writing for days,

drafts, carbons, poems are scattered everywhere,

and I want to show her one poem

which is the poem of my life. But I hesitate,

and wake. You’ve kissed my hair

to wake me. I dreamed you were a poem,

I say, a poem I wanted to show someone . . .

and I laugh and fall dreaming again

of the desire to show you to everyone I love,

to move openly together

in the pull of gravity, which is not simple,

which carries the feathered grass a long way down the upbreathing air.”

The late-70s: Rich produced key socio-political essays, including: ‘Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence‘, one of the first to address the theme of “lesbian existence”. In this essay, she asks “how and why women’s choice of women as passionate comrades, life partners, co-workers, lovers, community, has been crushed, invalidated, forced into hiding“. (Wikipedia) The essay was also published as a slender volume in 1981.

Adrienne Rich:

“The work that lies ahead, of unearthing and describing what I call here lesbian existence, is potentially liberating for all women. It is work that must assuredly move beyond the limits of white and middleclass Western women’s studies to examine women’s lives, work, and groupings within every racial, ethnic, and political structure. There are differences, moreover, between lesbian existence and the lesbian continuum–differences we can discern even in the movement of our own lives. The lesbian continuum, I suggest, needs delineation in light of the double-life of women, not only women self-described as heterosexual but also of self-described lesbians. We need a far more exhaustive account of the forms the double-life has assumed. Historians need to ask at every point how heterosexuality as institution has been organized and maintained through the female wage scale, the enforcement of middle-class women’s “leisure”, the glamorization of so-called sexual liberation, the withholding of education from women, the imagery of “high art” and popular culture, the mystification of the “personal” sphere, and much else. We need an economics that comprehends the institution of heterosexuality, with its doubled workload for women and its sexual divisions of labor, as the most idealized of economic relations.”

Some of the essays she wrote from this period were republished in ‘On Lies, Secrets and Silence: Selected Prose, 1966–1978’ in 1979. “In integrating such pieces into her work, Rich claimed her sexuality and took a role in leadership for sexual equality.” (Wikipedia)

From 1976-79 she worked as Professor and in 1979 herself and her partner moved to the West Coast and Santa Cruz, about 120km south of San Francisco, where she continued to teach, as well as produce work both as poet and essayist (“…maybe filling a notebook herself / with secrets she has never sold). For the rest of her life Rich would both write, publish and reflect on the challenges of her situation as a poet and a woman in an unfinished world. “I’m not talking about literary “intertextuality” or a “world poetry” but about what Muriel Rukeyser said poetry can be: an exchange of energy, which, in changing consciousness, can effect change in existing conditions….” she was to say in 2006, at the plenary lecture at the Conference on Poetry and Politics at Stirling University, Scotland and which she also read at the National Book Awards and which eventually became the manuscript ‘Poetry & Commitment.’ She continued to produced prolifically – for example in the 1980’s: she published in 1982: ‘A Wild Patience Has Taken Me this Far: Poems 1978-1981’. In 1983: ‘Sources’. In 1984: ‘The Fact of a Doorframe: Poems Selected and New, 1950-1984’. Also in June 1984, Rich presented a speech at the International Conference of Women, Feminist Identity, and Society in Utrecht, Netherlands titled ‘Notes Toward a Politics of Location’. “Her keynote speech is a major document on politics of location and the birth of the concept of female “locatedness.” (Wikipedia). The essay was later (1986) published in her prose collection ‘Blood, Bread, and Poetry – Selected Prose, 1979–1985′ which also includes the essay: “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence”. In 1986 also: ‘Your Native Land, Your Life: Poems.’ In 1989: ‘Time’s Power: Poems, 1985-1988‘… However: “…since the mid-50s, Rich has conceived of her poetry as a long process, rather than a series of separate books.” (Poetry Foundation) She also won numerous awards, including in 1986: the Inaugural Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize and in 1989 an honorary doctorate from Harvard University as well as the National Poetry Association Award for Distinguished Service to the Art of Poetry, also in 1989.

In 1991, in response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, George Bush invaded Iraq – Operation Desert Storm (17 January 1991 – 28 February 1991) filling television screens across the world:

Adrienne Rich: (‘Defy the Space That Separates’, 1996)

“…in a decade that began with the Gulf War and that has witnessed accelerated social disintegration, the lived effects of an economic system out of control and antihuman at its core. Contempt for language, the evisceration of meaning from words, are cultural signs that should not surprise us. Material profit finally has no use for other values, in fact reaps benefits from social incoherence and atomization, and from the erosion of human bonds of trust — in language or anything else. And so rapid has been the coming-apart during the years of the nineties…that some of us easily forget how the history of this Republic has been a double history, of selective and unequal arrangements regarding property, human bodies, opportunity, due process, freedom of expression, civility and much else. What is new: the official recantation of the idea that democracy should be continually expanding, not contracting — an idea that made life more livable for some, more hopeful for others, caused still others to rise to their fullest stature — an appeal to the desire for a common welfare and public happiness, above the balance sheets of profit…”

In the same year her next published work, ‘An Atlas of the Difficult World‘ (1991) – (“To a certain extent in Atlas, I was trying to talk about the location, the privileges, the complexity of loving my country and hating the ways our national interest is being defined for us.“) – won both the Los Angeles Times Book Award in Poetry and the Lenore Marshall/Nation Award (as well as the Poet’s Prize in 1993 and Commonwealth Award in Literature in 1991:

An Atlas of the Difficult World

II

Here is a map of our country:

here is the Sea of Indifference, glazed with salt

This is the haunted river flowing from brow to groin

we dare not taste its water

This is the desert where missiles are planted like corms

This is the breadbasket of foreclosed farms

This is the birthplace of the rockabilly boy

This is the cemetery of the poor

who died for democracy This is a battlefield

from a nineteenth-century war the shrine is famous

This is the sea-town of myth and story when the fishing fleets

went bankrupt here is where the jobs were on the pier

processing frozen fishsticks hourly wages and no shares

These are other battlefields Centralia Detroit

here are the forests primeval the copper the silver lodes

These are the suburbs of acquiescence silence rising fumelike

from the streets

This is the capital of money and dolor whose spires

flare up through air inversions whose bridges are crumbling

whose children are drifting blind alleys pent

between coiled rolls of razor wire

I promised to show you a map you say but this is a mural

then yes let it be these are small distinctions

where do we see it from is the question

“Rich’s poetry has maintained its overtly political, feminist edge throughout the decades since the Vietnam War and the social activism of the 1960s and 70s” (Poetry Foundation)….continuing to contribute to a wide number of personal and social concerns from the time of her move to California to her death in 2012 arising from her relationship to language and her position there as poet as well that of a woman whose real identify has been lost/displaced (?) or as an intellectual whose question is continuously compelled to seek for its answer beneath each surface:

Adrienne Rich: (From: ‘On Lies, Secrets, and Silence: On History, Illiteracy, Passivity, Violence, and Women’s Culture‘ )

“The television screen has throughout the world replaced, or is fast replacing: oral poetry; old wives’ tales; children’s story-acting games and verbal lore; lullabies; “playing the sevens”; political argument; the reading of books too difficult for the reader, yet somehow read; tales of “when-I-was-your-age” told by parents and grandparents to children, linking them to their own past; singing in parts; memorization of poetry; the oral transmitting of skills and remedies; reading aloud; recitation; both community and solitude. People grow up who not only don’t know how to read, a late-acquired skill among the world’s majority; they don’t know how to talk, to tell stories, to sing, to listen and remember, to argue, to pierce an opponent’s argument, to use metaphor and imagery and inspired exaggeration in speech; people are growing up in the slack flicker of a pale light which lacks the concentrated burn of a candle flame or oil wick or the bulb of a gooseneck desk lamp: a pale, wavering, oblong shimmer, emitting incessant noise, which is to real knowledge or discourse what the manic or weepy protestations of a drunk are to responsible speech. Drunks do have a way of holding an audience, though, and so does the shimmery ill-focused oblong screen.”

In 1997, the poet made headlines [Poet Adrienne Rich Refuses to Accept National Medal for the Arts, Democracy Now, July 16, 1997] when she refused the National Medal of Arts for political reasons. “I could not accept such an award from President Clinton or this White House,” she wrote in a letter published in the New York Times “because the very meaning of art, as I understand it, is incompatible with the cynical politics of this administration…[Art] means nothing if it simply decorates the dinner table of the power which holds it hostage.” Rich was also protesting against the House of Representatives’ vote to end the National Endowment for the Arts as well as other policies of the Clinton Administration regarding the arts generally and literature in particular.

Adrienne Rich: (‘Why I Refused the National Medal for the Arts‘, LA Times Books, August 3, 1997)

“Whatever was “newsworthy” about my refusal was not about a single individual–not myself, not President Clinton. Nor was it about a single political party. Both major parties have displayed a crude affinity for the interests of corporate power while deserting the majority of the people, especially the most vulnerable. Like so many others, I’ve watched the dismantling of our public education, the steep rise in our incarceration rates, the demonization of our young black men, the accusations against our teenage mothers, the selling of health care–public and private–to the highest bidders, the export of subsistence-level jobs in the United States to even lower-wage countries, the use of below-minimum-wage prison labor to break strikes and raise profits, the scapegoating of immigrants, the denial of dignity and minimal security to our working and poor people. At the same time, we’ve witnessed the acquisition of publishing houses, once risk-taking conduits of creativity, by conglomerates driven single-mindedly to fast profits, the acquisition of major communications and media by those same interests, the sacrifice of the arts and public libraries in stripped-down school and civic budgets and, most recently, the evisceration of the National Endowment for the Arts. Piece by piece the democratic process has been losing ground to the accumulation of private wealth.

There is no political leadership in the White House or the Congress that has spoken to and for the people who, in a very real sense, have felt abandoned by their government…

Marxism has been declared dead. Yet the questions Marx raised are still alive and pulsing, however the language and the labels have been co-opted and abused. What is social wealth? How do the conditions of human labor infiltrate other social relationships? What would it require for people to live and work together in conditions of radical equality? How much inequality will we tolerate in the world’s richest and most powerful nation? Why and how have these and similar questions become discredited in public discourse?”

On the issue of Rich’s complex relationship to Marxism, “Poet and scholar” Julie R. Enszer wrote:

“In the 1970s Rich expressed doubts about Marxism, particularly how men on the Left used feminism and racism to discredit the WLM. During the 1990s, Rich, an autodidact, studied Marxism seriously. Her 2001 essay collection, Arts of the Possible, argues passionately for the importance of socialism in contemporary debate. Rich wrote, ‘Marx’s depiction of early nineteenth-century capitalism and its dehumanizing effect on the social landscape rang truer than ever at the century’s end.’ Stating ‘[t]he questions Marx raised are still alive and pulsing,’ she encouraged people ‘to become less afraid to ask the still-unanswered questions posed by Marxism, socialism, and communism. Not to interrogate old, corrupt hierarchical systems, but to ask anew, for our own time: What constitutes ownership? What is work? How can people be assured of a just share in the products of their precious human exertions? … How much inequality will we go on tolerating in the world’s richest and most powerful nation?’ In her most recent prose collection, A Human Eye, Rich continued her engagement with radical political traditions with meditations on Che Guevara, Rosa Luxemburg and Muriel Rukeyser. Rich’s work was not without controversy. Her open discussions about feminism and lesbianism caused some literary critics to diminish her work. Some feminist critics situate Rich as an essentialist — invested in the inherent good of women to the exclusion of understanding the role of social construction in sex and gender — particularly Of Woman Born. This is a reductionist understanding of Of Woman Born and of Rich’s oeuvre in general.”

Adrienne Rich (‘Credo of a Passionate Skeptic’ LA Times, March 11, 2001)

“It interests me that in “Women and Honor,” that poetically terse piece of writing, I first invoked the name of Marx–to dismiss Marxism “for women.” I was of course echoing the standard anti-Marxism of the postwar American cultural and political mainstream. But, as I indicate in “Raya Dunayevskaya’s Marx,” written more than a decade later, this anti-Marxism, uncriticized and uninvestigated, was present also in the women’s movement. Marxism was tainted there, both by garden-variety anticommunism and by the fear that class would erase gender once again, when gender was just beginning to be understood as a political category.

Sometime around 1980 I felt impelled to go back and read what I had dismissed or felt threatened by: I had to find out what Marx, along the way of his own development, had actually written. I began working my way through those writings, in the assorted translations and editions available to me, an autodidact and an outsider, not an academic or post-Marx Marxist. There were passages that whetted my hunger; others I traversed laboriously and in intellectual fatigue. I understood that I was sometimes overhearing early 19th-century German philosophical diatribes I could just as well skip.

What kept me going was the sense of being in the company of a great geographer of the human condition, and specifically, a sense of recognition: how profit-driven economic relations filter into zones of thought and feeling. Marx’s depiction of early 19th-century capitalism and its dehumanizing effect on the social landscape rang truer than ever at the century’s end.

Along with that flare of recognition came profound respect and empathy for Marx’s restless vision of human capacities and the nature of their frustration. I found no blueprint for a future utopia but a skilled diagnosis of skewed and disfigured human relationships. I found a Marx who would have been revolted by Stalinism, by the expropriation of his ideas in the name of tyranny, by the expropriation of his name: “I am not a Marxist,” he said. In the feminism I had embraced, as in the social field where it was rooted, there was a salient dialectic: racism as destructive presence, race as great social teacher. Time and again racial actualities pushed against the “primary oppression” of gender; time and again the lesson was forgotten. I came to realize that we were afraid: that a focus on class (read Marxism) might blot out a focus on gender and race; that gender (feminism) might blot out race and class; that you could look at history and see the big eraser wiping out each successive lesson of justice, so that collective knowledge could not accumulate. For the pressing motif of this excessive society was and is: There is not enough (space, livelihood, validation) for all.

I’m not sure that I could have read Marx with so much patience and appetite had I not participated in the inevitable shortcomings of the feminist movement in the United States. Though some feminists (mostly women of color) insisted on intersections of race, class, and gender, emphasis was more often laid on women’s individual class identifications and how they negotiated them, or on poverty and welfare, than on how class, poverty and the need for welfare are produced and perpetuated in the first place. (Both kinds of work, of course, are necessary.) Elsewhere, movement was being parochialized into “women’s culture.” Meanwhile, the expansion of capitalism’s force field, the impoverishment of women within it, and the steep concentration of wealth were all brutally accelerating…”

In 2011, in her last volume of poetry published in her lifetime (‘Tonight No Poetry Will Serve’) there is a poem to Walter Benjamin, both ‘Jewish’ and ‘Marxist’ refugee, written in 2007, when she is 78 years old and 67 years after the suicide of Benjamin on the French/Spanish border at Port Bou, 26 September 1940, in flight from the Nazis:

Benjamin Revisited

The angel

of history is

flown

now meet the janitor

down

in the basement who

shirtless smoking

has the job of stoking

the so-called past

into the so-called present

No longer “angels” now but “janitors” in a time of endings…on a day this week, March 27, 2012, Adrienne Rich, 82 years old, died of complications from rheumatoid arthritis (from which she had suffered for many years), at her home in Santa Cruz, in California…

Adrienne Rich:

Ballade of the Poverties (for James and Arlene Scully, 2009)

There’s the poverty of the cockroach kingdom and the rusted toilet bowl

The poverty of to steal food for the first time

The poverty of to mouth a penis for a paycheck

The poverty of sweet charity ladling

Soup for the poor who must always be there for that

There’s poverty of theory poverty of swollen belly shamed

Poverty of the diploma or ballot that goes nowhere

Princes of predation let me tell you

There are poverties and there are poverties

There’s the poverty of cheap luggage bursted open at immigration

Poverty of the turned head averted eye

The poverty of bored sex of tormented sex

The poverty of the bounced check poverty of the dumpster dive

The poverty of the pawned horn of the smashed reading glasses

The poverty pushing the sheeted gurney the poverty cleaning up the puke

The poverty of the pavement artist the poverty passed out on pavement

Princes of finance you who have not lain there

There are poverties and there are poverties

There is the poverty of hand-to-mouth and door-to-door

And the poverty of stories patched up to sell there

There’s the poverty of the child thumbing the Interstate

And the poverty of the bride enlisting for war

There is the poverty of stones fisted in pocket

And the poverty of the village bulldozed to rubble

There’s the poverty of coming home not as you left it

And the poverty of how would you ever end it

Princes of weaponry who have not ever tasted war

There are poverties and there are poverties

There’s the poverty of wages wired for the funeral you

Can’t get to the poverty of bodies lying unburied

There’s the poverty of labor offered silently on the curb

The poverty of the no-contact prison visit

There’s the poverty of yard-sale scrapings spread

And rejected the poverty of eviction, wedding bed out on street

Prince let me tell you who will never learn through words

There are poverties and there are poverties

You who travel by private jet like a housefly

Buzzing with the other flies of plundered poverties

Princes and courtiers who will never learn through words

Here’s a mirror you can look into: take it: it’s yours.

Adrienne Rich (from ‘What Is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics’):

“This is the difference between the United States and Turkey in the late 1930s, when the revolutionary poet Nazim Hikmet was sentenced to twenty-eight years in prison “on the grounds that the military cadets were reading his poems.” This is the difference between the United States and Greece, where, both in the 1930s and after World War II, the socialist poet Yannis Ritsos was interned in concentration camps, exiled, placed under house arrest, his writings burned. This is the difference between the United States and the Stalinized Soviet Union, when the poet Osip Mandelstam (among countless other writers, in Russian and Yiddish, murdered in those years) was persecuted and exiled for an anti-Stalin poem, or, in the 1970s, the poet Natalya Gorbanevskaya sent to a “penal mental institution,” or, in the 1980s, the poet Irina Ratushinskaya to a prison for “dangerous state criminals.” This is the difference between the United States and Chile in 1973, where the junta who came into power the day of Pablo Neruda’s death sacked the poet’s house and banned his books….In the United States, depending on who you are, suppression is qualitatively different. So far, it’s not a question of creating human martyrs, since the blacklisted writers of the McCarthy era, although artists denied state and federal funding as “obscene” are under government censorship, and efforts to deport the writer Margaret Randall, based on her writings, were vigorously pursued for five years by the INS. Instead, poetry itself—I mean not words on paper only, but the social recognition and integration of poetry and the imaginative powers it releases—poetry itself is “banned” (in the terminology of the South African apartheid laws: forbidden to speak in public, forbidden to be quoted, to meet with more than one or two persons at the same time). Poetry itself, in our national life, is under house arrest, is officially “disappeared.” Like our past, our collective memory, it remains an unfathomed, a devalued, resource. The establishment of a national “Poet Laureateship” notwithstanding, poetry has been set apart from the practical arts, from civic meaning. It is irrelevant to mass “entertainment” and the accumulation of wealth—thus, out of sight, out of mind.”

During the course of a long life, Adrienne Rich published more than 25 poetry collection and 8 collections of essays as well as, for what it is worth, winning numerous awards…

Surely there is much to be explored and learnt within the vast intellectual and feeling world of this contemporary American writer, not least her consistent effort to prise open the steel lid on a society that has achieved hegemony over so much of our thought and practice, at least in the developed sectors of an increasingly unequal unjust globalised world. What is there to learn, then? What else, maybe, other than to dive deep into the wreck of the ship our affluent societies have become at the price of coming close to, or actually rendering, language almost meaningless? It is Rich’s deep alienation from the world of thought and feeling of this dominant yet superficial discourse (that of course covers up and protects power and privilege) that, alongside her excluded position as a woman, should serve to those of us coming later as a signpost, likewise for for those of us unhappy with the comfortable lies of contemporary capitalism, as well as so many of us excluded because of our differences or of our wanting-other or desiring-to-be-different to the superficial yet powerful outrages of this commodified universe. Despite the complexity of her thought as well as her complex explorations beneath the surface in order to name what is of hope or truth or promise to be found there, among the wreckage, the poet, in the unraveling of her work as it developed year after year, should become one more sister or brother or comrade in our struggle to resist the banal, to question the obvious, to challenge the powerful and to return to us all the promise of a steel-hard-yet-tender truth projected, like a promise, into a history with its opposite, often its ugly-violent-opposite, as its dominant impulse…

Margalit Fox (New York Times Obituary, 27 March 2012):

“Triply marginalized — as a woman, a lesbian and a Jew — Ms. Rich was concerned in her poetry, and in her many essays, with identity politics long before the term was coined…For Ms. Rich, the personal, the political and the poetical were indissolubly linked; her body of work can be read as a series of urgent dispatches from the front…In a 1984 speech she summed up her reason for writing — and, by loud unspoken implication, her reason for being — in just seven words. What she and her sisters-in-arms were fighting to achieve, she said, was simply this: ‘the creation of a society without domination.'”

Eve Endless (The Guardian, 6 April 2012):

“Adrienne Rich’s poems were acts of change, explosive political entities, never tricks or games or vain displays of craft (although they were exquisitely crafted). Reading her, I understood that poets were not meant to hover above the world; poems were burned in the grief, loneliness and outrage of the world. Her poems were rhythmic mappings of survival. She did not mean to be an activist. She meant to tell the truth in the language of her body. Her poems broke taboos and questioned the givens. I read “The Blue Ghazals” when I was 18 years old, and Rich made me believe for the first time that perhaps the bifurcation of struggle and song was not in fact the path to great literary achievement, but instead a dangerous road to narcissism, abstraction and denial…

She taught me that the lives of women existed in the future. And that language was the pathway to that future. She taught me women were living lives inside constructs of lives and that poetic grace and surprise could reveal and shatter those constructs…

She taught me women could be angry – and that anger is fertiliser. And she taught me that ‘… poetry can break isolation, show us to ourselves when we are outlawed and made invisible, remind us of beauty where no beauty seemed possible, remind us of kinship where all that seems possible is separation'”.

Lawrence Joseph:

“For Rich, the poet inside a wrecked society must will an imagined common language to get to human love, which is for her the central subject of any personal or social order. A poetry of ideological commitment must enter the heart and mind, become as real as one’s body, as vital as life itself—that’s what makes it poetry.”

Julie R. Enszer:

“Rich was keenly engaged intellectually and politically in struggles for justice; her work as a writer reflects these political commitments. Over a long life with a prodigious literary output, Adrienne Rich demonstrated repeatedly the importance of, and her commitment to, the will to change.”

Adrienne Rich: (‘Defy the Space That Separates’)

“We need poetry as living language, the core of every language, something that is still spoken, aloud or in the mind, muttered in secret, subversive, reaching around corners, crumpled into a pocket, performed to a community, read aloud to the dying, recited by heart, scratched or sprayed on a wall. That kind of language.”

Emily Taylor Merriman: (‘Catch if you can your country’s moment’):

“During Adrienne Rich’s career her formal poetic skill and evolving technical strategies have served, exemplified and sometimes even embodied her social and political goals. Over more than fifty years, from such early verse as “Aunt Jennifer’s Tigers” (1951) through “Planetarium” (1968), “An Atlas of the Difficult World” (1991), and “Terza Rima” (2001), the prolific Rich, driven by “inner necessity”…has used her ability to compose exquisite English verse in service of her aim of reorganizing social structures, liberating the oppressed, and establishing connections between marginalized groups of people. Her prose writings, too—the highly influential feminist treatise Of Woman Born (1976), for example, as well her direct comments on the development of her own craft in short essays like “When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Revision” (1971)—articulate her sociopolitical analyses and her hopes for change. They provide a useful but non-determining frame of reference for comprehending her poetic themes and methods. Rich’s poetry consistently demonstrates her desire to marry her remarkable technical abilities to a transformative political vision that will bear the fruit of ‘freedom’.”

Adrienne Rich (‘Credo of a Passionate Skeptic’, LA Times, March 11, 2001)

“I believe in the necessity for a poetic language untethered from the compromised language of state and media. Yet how, I have wondered, can poetry persist as a ligatory art rather than as an echo chamber of fragmentation and alienation? Can the language of poetry become too abstract (some might say elitist) even as it tries to claim what Octavio Paz has called “the other voice”? Is there a way of writing on the edge? Of course I think there is, and has been; I test my own work from that likelihood. “Language,” I find in Marx, “is the presence of the community.” In a 1979 essay by Gary Snyder: ‘The community and its poetry are not two.'”

Mark Doty (Afterword: ‘Poetry and Commitment, An Essay‘, 2007):

“Her lived commitment to questioning and revealing the structures of power and how we live within them turns out to be “the huge rockshelves” under her work, as Rich put it once in a great poem called “Transcendental Etude.” These rockshelves are the ground upon which she has founded a sustaining poetic, a life’s work—but also the ground upon which to build her profoundly generous gift to others: a deep, public valuing of the common life…Her poems are foundational texts of our time, and, in the future, when readers want to understand the great reconsideration of gender and power that reshaped American life, it is to Rich’s poems that they will turn.

Her restless empathy for those not in positions of power—women, the poor, laborers, queer women and men, the immigrant—is the ethical basis of her art. And if the critic in his position of aesthetic purity believes that poems suffer from it, then perhaps we’ve labored under a hobblingly narrow definition of poetry, a fiction of a realm in which words in their harmonies and shadings operate at a remove from the world, in some sacred grove. That idyllic glen, if it ever existed, was entered by human traffic long ago, and where people live, inequity resides. Rich has spent her entire career gazing into that difficult truth.”

Adrienne Rich (‘Credo of a Passionate Skeptic’, LA Times, March 11, 2001)

“At times in the past decade and a half I have felt like a stranger in my own country. I seem not to speak the official language. I believe many others feel like this, not just as poets or intellectuals but as citizens–accountable yet excluded from power. I began as an American optimist, albeit a critical one, formed by our racial legacy and by the Vietnam War. In both these cases it was necessary to look hard truths in the face in order to change horrible realities. I believed, with many others, that my country’s historical aquifers were flowing in that direction of democratic change. I became an American skeptic, not as to the long search for justice and dignity, which is part of all human history, but in the light of my nation’s leading role in demoralizing and destabilizing that search, here at home and around the world. Perhaps just such a passionate skepticism, neither cynical nor nihilistic, is the ground for continuing.”

And finally, it seems that Adrienne Cecile Rich, unlike Ethel Rosenberg murdered June 19, 1953 by the darkness that American society seems unable to adequately confront, did manage to join the march to “take back the night (“Ethel Greenglass Rosenberg would you / have marched to take back the night“), as well as “collecting signatures for battered women who killed” and again, unlike Ethel Rosenberg, Rich lived a long and productive life and spoke much so we have a record to explore “what she would have to tell us” (“What would you have to tell us / would you have burst the net“). Whether she “has burst the net” then, maybe it will be for our collective future, if we survive, to judge…

Adrienne Rich (‘Poetry and Commitment, An Essay‘, 2007):

“But—let’s never discount it—within every official, statistical, designated nation, there breathes another nation: of unappointed, unappeased, unacknowledged clusters of people who daily, with fierce imagination and tenacity, confront cruelties, exclusions, and indignities, signaling through those barriers—which are often literal cages—in poetry, music, street theater, murals, videos, Web sites—and through many forms of direct activism…”

REFERENCES, SOURCES & Links (thanks to)

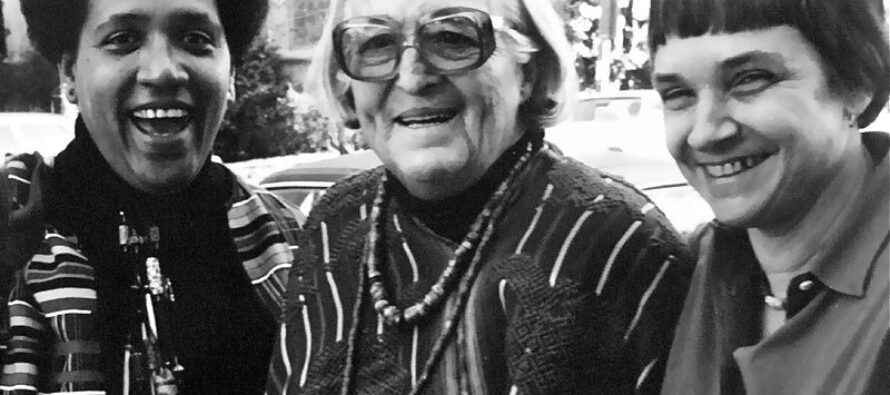

Image

By K. Kendall from Portland, OR, USA (Audre Lorde, Meridel Lesueur, Adrienne Rich 1980) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Partial Bibliography

Papers

http://oasis.lib.harvard.edu/oasis/deliver/~sch00021

Rich, Adrienne, Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence

http://people.terry.uga.edu/dawndba/4500compulsoryhet.htm

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poets/detail/adrienne-rich

Sources & References:

Books explored:

Rich, Adrienne, “What Is Found There.” W. W. Norton & Company, 2015.

Rich, Adrienne, “Later Poems: Selected and New.” W. W. Norton & Company, 2013.

Rich, Adrienne “Of Woman Born Motherhood as Experience and Institution“, W. W. Norton & Company, 1976.

Rich, Adrienne, “On Lies, Secrets, and Silence, Selected Prose 1966–1978” W. W. Norton & Company, 1979.

Rich, Adrienne, “An Atlas of the Difficult World.” W. W. Norton & Company, 1991.

Rich, Adrienne, “Poetry and Commitment.” W. W. Norton & Company, 2007.

Rich, Adrienne, “A human eye: essays on art in society, 1996–2008” W. W. Norton & Company, 2009.

Essays:

http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/m_r/rich/onlineessays.htm

Emily Taylor Merriman: in “Recovery and Regeneration in the Poetry of Adrienne Rich” (Edited by William S. Waddell) Cambridge Scholar Publishing, 2007

References:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2002/jun/15/featuresreviews.guardianreview6

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/apr/06/adrienne-rich-eve-ensler-jackie-kay

https://www.thoughtco.com/of-woman-born-by-adrienne-rich-3528976

https://newrepublic.com/article/132117/adrienne-richs-feminist-awakening

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/29/books/adrienne-rich-feminist-poet-and-author-dies-at-82.html

http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/m_r/rich/bio.htm

http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/m_r/rich/wreck.htm

http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/m_r/rich/progressive.htm (Interview)

https://www.solidarity-us.org/node/3684

https://www.democracynow.org/1997/7/16/national_medal_for_the_arts

http://www.npr.org/2012/03/29/149619634/adrienne-rich-resolution-amid-the-turbulence

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poets/detail/adrienne-rich

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adrienne_Rich

Audio:

Substantial Sound Archive of the poet reading her work

https://writing.upenn.edu/pennsound/x/Rich.php

Video:

Democracy Now, Obituary

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lJH4Y-ylOzE

Adrienne Rich: “For Ethel Rosenberg”

What Kind of Times Are These.”

Related Articles

‘Living Together in Spite of Our Differences’: A Talk with Amin Maalouf

![]()

The Abu Dhabi International Book Fair opened this year on April 27, the morning after the International Prize for Arabic Fiction was announced, and closes today

33 Years Later: Memory and Violence in Literary Sabras and Shatilas

![]()

It’s now been thirty-three years since the Sabra and Shatila massacres in Lebanon’s Palestinian refugee camps. They continue to show up in novels, poems, and memoirs

Entrevista con Alain Badiou

![]()

Todo lo que necesitas es amor Eduardo Febbro Página/12 Alain Badiou es un pensador que podría llamarse polifónico: ha abordado