The tragedy and courage of Ballymurphy

![]()

Today – Wednesday – the Dáil debate an all-party motion in support of the Ballymurphy Massacre Relatives. Their story is one of great tragedy, courage and tenacity. Its also a story of my home place – where I grew up and the people I knew. Below are my remarks from today.

Support the Ballymurphy Families!

Ba mhaith liom mo bhuíochas a ghabháil leis an Taoiseach as díospóireacht uile-pháirtí an lae. Seo céim thábhachtach chun tosaigh do theaghlaigh Bhaile Uí Mhurchú agus iad sa tóir ar an fhírinne agus cóir.

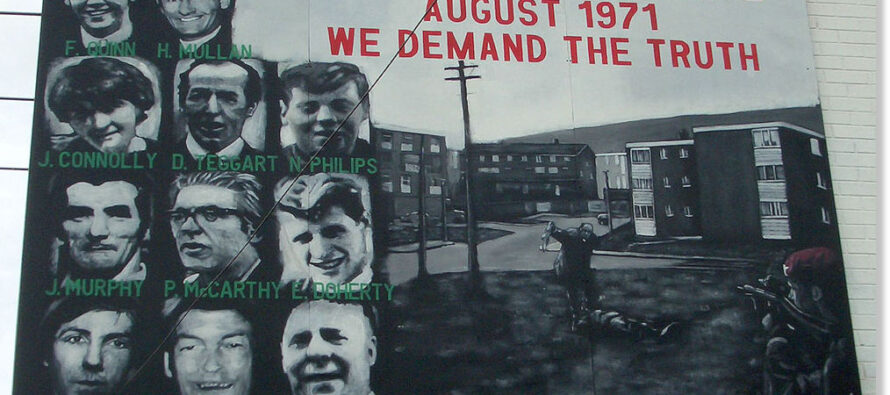

Today’s motion is an important step forward in the search for truth and justice for the Ballymurphy families. Ballymurphy is a large housing estate at the foot of Black Mountain in west Belfast. Like other housing estates throughout these islands, it was badly built in the 1950s – jerry-built houses in an area which lacked many of the basic facilities for education, recreation, jobs, and for young people. My mother was allocated a home there in the late 1950s, so the people who are gathered in the Visitors Gallery today are my neighbours or the children or grandchildren of my neighbours and friends. They are the relatives of the 11 citizens killed in Ballymurphy in August 1971. Tá fáilte mhór rompu uilig.

I also want to welcome the British ambassador, Dominick Chilcott, here today. I trust he will convey the feeling of this Oireachtas to his Government and ask why, decades into a peace process, the Government in London does not accept the right of these victims of British state terrorism to have their truth acknowledged.

I also welcome the relatives of some of the victims of the McGurk’s pub bombings, who have accompanied the Ballymurphy relatives today. Tá gaolta na ndaoine seo ag lorg na fírinne. They are the victims of a war which commenced in the north-eastern part of the island in the late 1960s. War was the British state’s response to the civil rights struggle. The Irish Government of the day stood idly by as ordinary people found themselves caught up in a carnival of reaction against very modest demands for civil rights.

On 9 August 1971, internment was introduced. By that time British troops had been on the streets for two years. They enforced their will through curfew, rubber bullets, gas, water cannon and lead bullets. On the back of the initial internment swoops, the Parachute Regiment was deployed in Ballymurphy. They, like the royal marine commandos, were the shock troops of the British military, deployed against communities which were deemed to be particularly rebellious. When I was growing up in Ballymurphy it was not particularly rebellious at all, but the events of 1969, 1970 and 1971 politicised and republicanised an entire community. Ballymurphy never went to war. The war came to us.

The bombing at McGurk’s pub in north Belfast was another horrific example of that war. It took place in December 1971, four months after the events in Ballymurphy. In both instances, as in many others involving British state forces, the establishment sought to cover up and to deny any responsibility for the deaths. The McGurk’s families have initiated legal proceedings against the PSNI, the British Ministry of Defence and the Norther Ireland Office, NIO.

An investigation by the Police Ombudsman for the North found the RUC had exhibited an investigative bias by blaming the loyalist attack on republicans. New evidence uncovered by researchers for the families at the British National Archives in London reveals links between the McGurk’s bar bombing and other similar incidents, including the Kelly’s bar attack on 13 May 1972 in Ballymurphy. These links provide evidence of collusion between British state agencies and Unionist death squads. We have also seen this in the recent RTE and BBC television programmes which looked at collusion, and which reinforce the view that the issue of collusion warrants a stand-alone debate in this Dáil. We have put this case to the Taoiseach and I ask once again that a debate be scheduled in the autumn.

Ach inniu táimid ag díriú isteach ar an slad a tharla i mBaile Uí Mhurchú.

For the Ballymurphy families with us today, their story begins in the early hours of Monday, 9 August 1971. Thousands of British soldiers, supported by the RUC, smashed their way into hundreds of Nationalist homes.

I was in Ballymurphy that night. I watched my own home being smashed into.

I watched other male members of my family being dragged off. I watched my mother and my younger brothers and sisters fleeing. The house was occupied for days by the Parachute Regiment. They destroyed everything. They shit on beds, they urinated in wardrobes, they broke up family and religious memorabilia They dragged away over 300 men and boys into the night, many of them to be tortured later. In the following hours in the Murph, they shot dead ten citizens: nine men, including a local priest, and a mother of eight children. Contrary to what the Tánaiste implies, there was gunfire only from one side when these citizens were killed. That gunfire came from the Parachute Regiment.

The innocent victims were Fr. Hugh Mullan, Francis Quinn, Daniel Teggart, Joan Connolly – a mother of eight – Joseph Murphy, Noel Phillips, Edward Doherty, John Laverty, Joseph Corr and John McKerr. An 11th man, local community worker Paddy McCarthy, died from a heart attack after a British army patrol subjected him to a mock execution. Eleven families lost loved ones and 57 children were bereaved.

As a consequence of internment, many Belfast citizens fled their homes seeking safety in refugee camps in this State. Among them were some of the Ballymurphy families and their children. Some of those in the Visitors Gallery today watched the funerals of their parents on news footage broadcast by RTE. Others were too young to comprehend the enormity of what happened.

Five months later the same paras were on the streets of Derry and shot dead

14 people. The main difference between what happened on Bloody Sunday in Derry and what happened in Ballymurphy was that a part of the assault in Derry was televised. It immediately became a huge issue of controversy while, in Ballymurphy, only the people there knew what had happened. Of course, the British, the regiments, the commanders and the British Ministry of Defence knew.

Six months after Bloody Sunday, the paras returned to west Belfast and carried out another attack in Springhill, the housing estate adjacent to Ballymurphy, where they shot dead another five people, including three children and another Catholic priest. Two Catholic priests were killed in the one community. Margaret Gargan was aged 13, John Dougal was 16, Davy McCafferty was 15, Patrick Butler was aged 40 and the second Catholic priest, Fr. Noel Fitzpatrick, was aged 40.

For 44 years the Ballymurphy families, like many others, have demonstrated extraordinary courage and determination in the face of British secrecy and obstruction. Le fada an lá ní bhfuair scéal Bhaile Uí Mhurchú cluas éisteachta. It was the forgotten massacre. Ach d’fhág sé brón a bhí chomh fíor agus chomh trua le haon slad eile.

For four decades the families have campaigned with great dignity and with grace. I have accompanied them to meet successive British Secretaries of State and shadow Secretaries of State. Truth to tell, I have lost count of the number we met. None of them did anything of any consequence, although some of them were moved to tears by what they were told. We have also briefed successive taoisigh and Ministers for Foreign Affairs, and today the families briefed the Oireachtas. Are we also going to let them down? It is obvious that the memories from that cruel period in our history are still fresh and the pain and grief is as strong as it was 40 years ago, but the families have also refused to be broken. They have refused to hate.

They go forward with positivity. They have compiled significant evidence which shows that all who died were killed unlawfully and in breach of Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights, ECHR. The case also raises serious questions regarding human rights abuses committed by the British Army and exposes a culture of impunity in which members of the British forces routinely acted outside the law and were protected while so doing.

In November 2010 the families made an application to the Attorney General to re-open the inquests. A year later he agreed. That was a welcome development but the families and I remain concerned about the limitations of the inquest system. Consequently, they have proposed the appointment of an independent panel to examine all documents relating to the context, circumstances and aftermath of the deaths of their loved ones. The British Secretary of State has rejected this proposal. She is one in a long line.

For that reason the families are looking to the Government and to Oireachtas Members to demand that the British Government stop blocking and hiding and agree to an independent review. This all-party motion is an important step on the road to achieving that, but let no one think that voting for this is enough. It is not enough to say that we support the families or other victims. As the Dáil knows only too well from its experience with successive British Governments in respect of the Dublin and Monaghan bombings, for example, motions on their own will not make a difference.

The Government has not done it yet, but it needs to put in place a strategic approach which ensures the British Government is challenged on this issue at every meeting and in every international forum. Unless we do that, the British Government will continue to refuse to give the people of Ballymurphy, and in particular the families and other families what they deserve. If our Government does not do it, how on earth can we expect anyone else to do it? If we are not making this the main issue of this time on the back of the all-party Oireachtas motion we cannot expect anyone else to do it. The matter must be on every agenda between Irish and British officials. The full resources of the State must be employed to challenge the actions that took place. It would be good for the people of Britain for the lid to be lifted on this phase of our joint history. It is not enough to raise the issue, tick the box and talk quietly on the side. It is only when one has a build-up, using diplomatic and other influences, that one will get the British Government to respond as it did on Bloody Sunday. Of course Mr. Cameron deserves commendation for his apology at that time, but we should remember that it too took decades to get.

We should not forget the pain, suffering and tragedies from decades of conflict because for many they are as real today as they were when they first occurred. Almost 4,000 people died and countless others were injured in a war that was vicious and brutal. Fuair tuairim is ceithre mhíle duine bás le linn cogadh a bhí géar uafásach. Over the years I have met many victims, including victims of the IRA. I am prepared to do that, as are other leaders of Sinn Féin. The grief of all victims of the conflict must be respected and acknowledged and all of us in political leadership have a responsibility to do all that we can to ensure no future generation suffers the pain of war. We who have survived have a duty to set them free. For many however, the past remains a reality of the present. Even though it was over 40 years ago, it is as if it was yesterday. I found myself getting emotional when making my opening remarks here today, even though it is almost half a century ago. The past is the present for so many people, and it remains an obstacle to dealing with the future or a pretext or excuse for refusing to build a new future of equality, fairness and prosperity for everyone.

For that reason Sinn Féin endorsed the measures in the Stormont House Agreement for addressing legacy matters. Notwithstanding the difficulties that exist, there is an onus on the Irish and British Governments to implement those elements of the Stormont House Agreement that deal with the past and legacy issues. There is no need to wait for the local political parties – none at all. Issues of security and for the forces involved are the responsibility of the two Governments. They are not the responsibility of Sinn Féin, the DUP, the UUP, the SDLP or the Alliance Party. The Governments can put together the process for dealing with the past and Sinn Féin will co-operate with it. The peace process needs continuous nourishment. It needs to be at the top of the Government’s agenda.

Notwithstanding any of the other political priorities, that is where we need to put it. Unfortunately, that is not the case currently, although the Oireachtas all-party motion is very welcome and is a good step in the right direction. I commend the motion to the Dáil.

Related Articles

BOICOTTAGGIO SCUOLE TURCHE

![]()

Migliaia di studenti curdi hanno boicottato il primo giorno di scuola a sostegno del diritto all’insegnamento della lingua madre.Gli studenti

IL PROFILO DEMOCRATICO – IÑAKI EGAÑA

![]()

Nell’anno 1928, il regista che sarà poi comunista, Mauro Azcona, diresse una dei primi film che vennero realizzati nel nostro

COLOMBIA: ELEZIONI E PARAMILITARI

![]()

Il Movimiento de Observacion Electoral (MOE) ha annunciato che 80 candidati al Congresso colombiano nelle elezioni svoltesi la scorsa settimana,